- Opinion

- 07 Dec 25

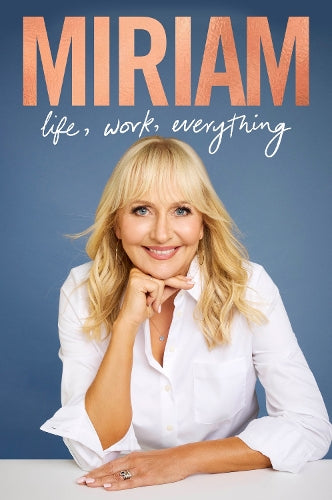

Miriam O’Callaghan: "I just hope people learn a little bit more about me – and think I’m an okay person at the end of it"

Having just released a fascinating new memoir, in a hugely compelling interview, veteran broadcaster Miriam O’Callaghan discusses the Troubles, personal loss, scandals, encounters with cranky musicians, and a whole lot more.

“I think my life doesn’t get any less busy,” says a voice down the phone with familiar South Dublin elocution. “But I’m delighted, because I have a strong view that this is our one and only life, and we should live it to the full.”

It might sound like a sentiment you’d find on your aunt’s kitchen wall, but in Miriam O’Callaghan’s case, she means it. Few have packed as much into one lifetime.

She’s been witness and narrator to modern Ireland. The Good Friday Agreement. Nation-shaping referendums. She’s had ministers come out as gay live on air, befriended the Clintons, and been responsible for making sense of the country’s biggest triumphs, as well as the tragedies that outnumber them, over the last 30-odd years.

This is all while raising eight kids, by the way. She’s earned the rare Irish distinction of first-name fame. Miriam shines in gold lettering at the top of her new memoir Life, Work, Everything, in which she explains her ‘ringside seat’ perspective on all of the above, and plenty more besides.

“I poured my soul, heart and inner being into it,” she continues. “I used to start writing at five in the morning because my days are so busy. I’d come home from Prime Time and go back and work late, writing and writing. What I hope people will take from it is that it’s an honest portrait of my life.

“I always ask people to open up to me and a lot of the time they do, like Leo Varadkar coming out as gay. People seem to trust me with their personal and private stories. So when I was going to write my memoir, I left no stone unturned.

“I try to be honest about the personal stuff in my life, and I just hope people learn a little bit more about me and think I’m an okay person at the end of it.”

Why was now the right time to write this book?

I got the contract 20 years ago from Penguin. I went on to have another son and I just never seemed to have the time to do it. Now, whether that was kind of an excuse…

I was nervous about writing it. Firstly, because the insecure 15-year-old in your head thinks, ‘Would anyone even be interested?’

Secondly, I have a shared life. I have eight children. A lot of siblings. A big huge family. My mum is still around. I didn’t want to write anything that would upset anybody close to me.

How conscious of that were you while writing?

It’s in my DNA. I honestly don’t understand how people go through life trying to hurt others, I just don’t get it. If you have something mean to say, just keep it to yourself. I don’t believe in rows. Some people say it’s ‘clearing the air’. I don’t believe in that.

People say things they don’t mean. That lingers and frankly, none of us forget anything anyone says if it’s hurtful.

I don’t believe in post-mortems in work either. Nobody comes in to do a bad job. So, if something goes wrong, let it go. There’s a new day today and there’s a new show tomorrow.

You started as a researcher on This Is Your Life. What pushed you towards current affairs over entertainment?

Probably that Irish voice in my head being like, ‘Don’t be ridiculous Miriam! You don’t belong in Hollywood, slugging champagne with Bob Hope.’

My dad came from a small farm in Kerry. He couldn’t afford to go to university, so he went into the civil service, as a lot of his generation did. My mom, who’s still alive, was a national school teacher, later a principal.

They would have had a very old-fashioned view. It’s come full circle now, that view of security, doing something sensible. It’s in my brain – that serious side from my father and my mother – it’s always there.

Ireland was different in the ’80s, especially for women. Did you always believe that you could become what you are now?

I’m not a reflective person. Writing a memoir was a nightmare because it forced me to reflect. I hate looking back, I don’t think there’s any point.

But yeah, Ireland was a very different place in the ’80s. I talk about that a bit in the book, where I worked in a law firm when the Me Too movement didn’t exist.

I definitely had one of those Me Too moments and in a beautiful serendipitous act – the young solicitor who saved me from a predatory older solicitor – his daughter became friends with my daughter. The ’80s were a very different time. We were a different country.

The Troubles is something you’ve been close to. Throughout your career, you’ve covered people dying and suffering. Does that take a mental toll?

I think it did, only because I had my first child when I was 26, and I started covering the North when I was about 29. Whether it’s what’s happening in Gaza or what was happening in the North, I think when you have your own child and you see immense suffering like the Warrington bombings, where the two little boys were killed, it impacts you quite profoundly.

I’ve always been opposed to political violence. That solidified the more I covered. Through my years working on Newsnight, you’d be going into these tiny homes in the estates and you see both sides of it. I remember thinking to myself that people suffering are often the most marginalised in society. I rarely did stories in the leafy Northern suburbs, and it made me realise that violence is totally counterproductive. It creates so much unhappiness. People sit beside empty chairs for the rest of their lives.

People never get over it. And they’re not meant to. If someone who belonged to you was blown up in a bombing, or shot dead, you’re never ever gonna get over that. And what did we achieve? Years on, we ended up with a peace process that was there decades earlier.

Was it difficult to write about losing your sister Anne to cancer?

I thought I would get upset writing about Anne and I didn’t. That’s because I’ve spoken about her consistently in every interview I’ve done. I always think it’s tragic enough to die, but you die twice if you’re forgotten. She was more well-known than I was when she died. People would always come up to me and say things like, ‘Oh I knew Anne in UCD.’ And I thought that was lovely.

The bit I got upset about was my dad dying. I realised at that moment his death had been overlooked. He wasn’t that old, he was in his mid-seventies, he was walking around to get a mass card eight weeks after Anne died – then he died, I’d say of shock and a broken heart. He just couldn’t believe what had happened.

So when I was writing about my dad, I did get upset. Anne had just died and I was so consumed with that tragedy at the time, that I probably overlooked my father’s death a little.

You said you started to live life on your own terms after their deaths.

The death of my sister was definitely my BC and AD, because until then, I foolishly thought that life was fair. I thought that if you worked hard, if you’re decent and kind to people, you could be sure that life was going to be kind back to you.

When Anne died, I thought that life had been robbed from her. I was so angry. I realised life is really unfair. I thought, ‘Okay Miriam, this is it. This is your one and only life. You’re going to do your best to be happy. You’re not going to worry and you’re going to live every day.’

On a lighter note, a privilege of having eight kids must be that you’re up-to-date with music.

One of my daughters worked for a big music company in New York, so she was telling me about Chappell Roan before anyone in the world had heard about her. So yeah, I’m very up-to-date.

I’m also a classical piano player. I play Mozart a lot just to relax myself. I don’t know if you’ve read my Van the Man story… but I still love Van Morrison.

Miriam O’Callaghan with Van Morrison

You had a difficult experience interviewing him.

My second interview with him was so bad it never went out.

I was surprised you were so upset by that.

I surprised myself. I can still see him walking into the room. I thought, ‘I don’t think this is going to go well’. I blamed myself, because he went off on one when I asked him to explain skiffle music. I had the explanation written in front of me, but I thought it would be better to come from Van.

Then it just went really wrong. I always think that I can pull an interview back. I’ve been in tricky scenarios before. But I couldn’t get Van back onside. Then it went from bad to worse. We got into the rabbit hole of Covid and why more people like me didn’t speak about the rules and how the rules were wrong. I was scrambling, saying, ‘It’s important for elderly women like my mom to be protected’. It was so bad I wanted him to walk.

But he didn’t. He just stayed there looking at me like he wanted to be anywhere else. I called the Universal Music people who were there and said, ‘Thank you very much. I’m really sorry it went so badly’. They said thank you and left. I was so shocked I started crying. I was just so disappointed with myself and I was so disappointed that it went so badly.

Why didn’t you turn around and say, ‘What is your problem?’

I know his music means a lot to a lot of people, but it meant everything to me. Van Morrison’s songs were the backdrop to the peace process. He is a genius and remains a genius and I adore his songs.

When I finally got my first interview with him [in 2018], I wrote a piece on the RTÉ website called ‘Do Meet Your Heroes’. It went so beautifully. I was excited for the second time and was so shocked that it went so wrong.

Did the fact that it went well the first time make the second time worse?

It did, because I had been told by other people that I’d find him tricky. But I thought he was joyous. Afterwards, his producer sent me a recording of Van’s mother singing, because I asked about his mom. She had a beautiful voice. I thought we were besties, so it was a bit of a blow when I realised no, he doesn’t love me. I still love him. And his music. I think it’s a bit unrequited at this stage…

You sued Facebook (and won), after your name and image were being used in scam posts. What’s your view on social media, as a journalist? Are you concerned by people like Elon Musk?

Yeah, it does worry me. The genie is out of the bottle. All you can do now is regulate the genie. I do think the world has been too slow to rein in these tech bros and huge social media sites.

The reason my Facebook thing is interesting is because I was someone who has a little bit of status in a tiny country. Within Ireland I had a little bit of power, and I couldn’t stop them telling these lies about me. I realised at that moment they didn’t care.

Imagine I was somebody else and people were posting terrible stuff about suicidal ideation or dangerous stuff about anorexia, where impressionable young people are watching this on a daily basis. It’s a terrifying monster that needs to be regulated massively.

What do you think social media has done to honest reporting?

It works both ways. In a way, it’s really good for publications like yours, or RTÉ. I think it helps credibility. People talk about the wild west and the jungle of online journalism, where people are just putting up untruths – or ‘truthiness’ as President Trump likes to talk about.

It’s a good time for mainstream journalism, because all the recent research is showing when push comes to shove, even young people go to more mainstream outlets to check the news and the facts.

I found Twitter to be such a wonderful thing. It’s sad that it’s become such a toxic platform. It used to be so fascinating. Instagram is a lovely platform. TikTok’s got a bit of that nasty stuff that X has and Facebook, I don’t use.

Is the public broadcaster having conversations about winning over young people? I’m 25. I’m not sure how many people my age are watching TV or listening to the radio.

But you watch it in different ways. The Six One News is a massively watched programme. I believe they get a 40% share of people watching television, which is massive. They get a lot of people from 35 upwards.

The website, that’s where a lot of young people check their stuff. A few years back, my young sons, who were students, were coming up to me with weird facts, saying, ‘Have you seen this?’ I said, ‘No, that’s not mainstream, that’s not true’. They themselves go to mainstream sites now. So, I really don’t worry. I’m not a worrier. You could spend your whole life worrying.

People like me, who believe in the power of brilliant journalism and factual, accurate journalism – this is a really good time for us, because the world’s such a crazy place. You need honest journalism.

A few years ago, there was the well-documented payments scandal at RTÉ. Were you bothered by your wages being public information?

When I started as a researcher and producer, my father was worried. I stopped becoming a lawyer and a lot of my friends who became lawyers became really wealthy.

I never thought going into broadcast journalism would make me good money. My father had convinced me that it was really bad and I wasn’t going to be a high earner for the rest of my life, so it never entered my head. But then, when all the men were earning certain figures, it seemed mad that women shouldn’t earn the same.

I mean, I know why they published the presenter salaries. I do think Ireland’s so small. In the BBC, they did it in bands and they did a hundred people, but in Ireland they just did 10 people. I understand why other broadcasters are leaving RTÉ, because they go somewhere like Newstalk or Today FM, and nobody knows what they earn and no one comments on it. It’s definitely a little bit odd.

The Oireachteas meetings. You mention the word ‘grandstanding’ in the book. Did that bother you and your colleagues? That politicians, who many people wouldn’t feel are doing a great job themselves, were getting up there and picking low hanging fruit?

No. I thought the kicking RTÉ got after the payment scandal was absolutely deserved. I constantly talk about trust, and if people don’t trust me, then I have lost everything. Why should they listen to what I say? Why should they trust any question I ask?

So, for me the kicking that was given was merited and warranted, because it was a gross breach of trust. At the Oireachteas meetings, most of the politicians were nice and decent. But there were a few who were definitely grandstanding, because they were getting huge views. I just didn’t like it. I realised for the first time how much they disliked the organisation I work in. So, it was revealing for me.

Why do you think people dislike your organisation?

I don’t believe people do dislike RTÉ. I mean if you look at all the papers today, right, because of the stories about RTÉ presenters changing on radio and the story about Ray D’Arcy, every paper has RTÉ on the cover.

I think people feel connected to it, because again, it’s such a tiny country and for a long time there was only RTÉ. I think they feel part ownership of it, and I think when we mess up, they feel it quite personally.

The BBC gets a huge kicking too in the UK. If you’re in a position of trust, and you are receiving taxpayers’ money, you need to be accountable to the citizens who pay for the licence fee. I’ve never forgotten that. I go around the country a lot. I find people really decent, and by and large, people know if someone’s being decent or not. I’ve been in their living room for 30 years, so if they hated me, they probably wouldn’t bother coming up to me.

What would you say are the differences between RTÉ and the BBC?

They’re so similar. I don’t know about ITV and Virgin Media. Everyone makes good programmes. But I just think because the BBC and RTE both get a licence fee, it’s never about the profits the company makes, because it’s not a commercial company. Obviously RTÉ has to straddle both of those, because it’s half-funded by ads.

So I think the only difference in the BBC is that it’s all licence fee, so it doesn’t have any of that commercial pressure, while RTÉ is half-funded by the licence fee. But the ethos and values, and the way they approach news and current affairs – having worked for a decade in the BBC, and now decades in RTE, they’re almost identical.

Have you seen a big shift after everything that’s happened in the last few years at RTÉ?

No. I find the people I work with, by and large, they’re the same people. People come in to do a good job. Everyone really felt it was funny when The Traitors went out. It was a weird high point for RTÉ, because everyone was talking about it.

It was the first time people really relaxed back into thinking, ‘Ah they’re good shows’. People in RTÉ felt some of the pressure was finally off and that the payments scandal is behind us.

If they brought out Celebrity Traitors Ireland, would you be up for it?

I won’t be on it! It’s funny, the audio cue woman the other night said, ‘Miriam I’m watching the BBC Celebrity Traitors, you have to go on it, you’d be amazing.’ I’ll probably be quite good as a traitor, which is a bad thing to say about myself. But I won’t be doing it.

• Miriam: Life, Work, Everything is out now via Penguin Sandycove.