- Opinion

- 08 Jan 26

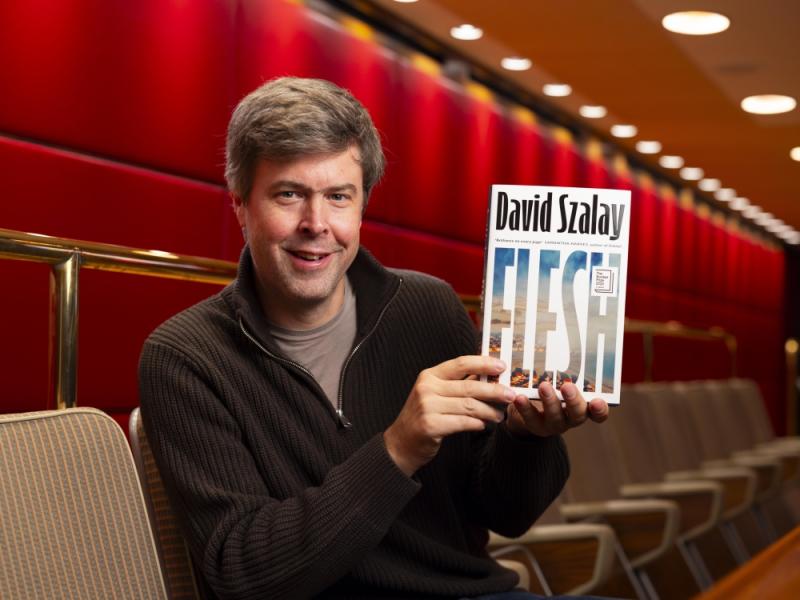

Booker Prize winner David Szalay: "Joyce was definitely a writer who mesmerised me as a young person"

Having become one of the literary stars of the moment thanks to the Booker-winning Flesh, which tells the rags- to-riches story of a young Hungarian man, David Szalay discusses writing about sex and violence, politics, Joyce, Bret Easton Ellis, Martin Amis, and not wanting to get caught up in the culture wars.

The winner of this year’s Booker Prize, David Szalay’s Flesh focuses on a young Hungarian man named Istvan. A virginal 15-year-old at the outset, he soon enters into a sexual relationship with a 42-year-old woman. After their relationship comes to an abrupt end in dramatic circumstances, Istvan – after a stint fighting in the Iraq war – ends up working as security for a wealthy London family.

When the husband dies due to natural causes, Istvan marries the young wife, although her son ultimately despises the new couple. Told in a spare, stripped back style, with a streak of dark humour, Flesh is a compelling exploration of sex, violence, social inequality and existential angst.

Roddy Doyle, chair of the Booker panel – other judges included Sarah Jessica Parker – said of the novel, “We had never read anything quite like it. It is, in many ways, a dark book but it is a joy to read.” Born in Montreal to a Canadian mother and a Hungarian father, 51-year-old Oxford alumnus Szalay moved to Beirut as a child.

After the onset of the Lebanese Civil War, the family relocated to London, with David eventually moving to Hungary to pursue his career as a writer. With a number of story collections and two other novels, All That Man Is and Turbulence, also to his name, Szalay counts Dua Lipa among his admirers, while Stormzy read an extract from Flesh to mark the Booker ceremony.

Elsewhere, the novel has also been optioned for a film adaptation. There’s no doubt about it – Szalay is one of the literary figures of the moment. So has the Booker win proved life-changing?

“I guess it will be,” says the author in his patrician-but-friendly tones, from his home in Vienna, where he lives with his wife. “It’s been a very busy two weeks, I can say that. Probably the busiest couple of weeks I’ve had for a very long time. The week after particularly was solid with commitments, things are just beginning to settle down now a bit. I’m only just starting to take in the fact of it actually, it’s quite a big thing to digest.”

David Szalay. Credit: David Parry for Booker Prize Foundation

One of the elements that most struck me about Flesh is the sense of intense alienation, reminiscent of Camus. Once again, it caused me to think that The Outsider is the most influential novel of the 20thcentury.

“Like many people – well not many, but some! – I read Camus as a teenager and I was very taken by him,” says Szalay. “I’m sure his writing is one of those foundational influences that you never quite get out of your system. It sort of becomes part of who you are, absolutely.”

In writing Flesh, the author also set out to explore the philosophical idea that the body, before the mind, is the first fact of existence – an idea closely associated with the films of body-horror maestro David Cronenberg.

“Well, Cronenberg isn’t specifically an influence,” says Szalay. “But obviously what you say about the body and physical experience being the starting point for everything, that was something the book quite deliberately and self-consciously set out to write to, as it were. As you say, it sort of takes you into fascinating philosophical territory, as much as anything else.”

It also creates an interesting tension in the story, with the emphasis being less on Istvan’s psychology – he expresses himself in often comically monosyllabic fashion – than his physical reactions to the external world.

“Yeah, that was definitely my aim,” nods the author. “I deliberately was writing about a relatively inarticulate and unforthcoming character, partly because I wanted to look at it very much as him responding physically, first of all. But also in more complex ways, emotionally and intellectually, as well. Looking at it largely from the outside, I think something interesting takes place.

“Because as a reader, I hope you feel very close to this character, finally. It’s not like you have no understanding of him, or I hope the reader doesn’t feel they have no sense of who this person is. But that is mainly achieved, I guess, by observing him from the outside, more than being stationed inside his head and having access to his continuous thoughts and internal reactions.

“I wasn’t primarily interested in looking at him as a sort of psychological case study or anything like that.”

Flesh is also notable for its intense sex scenes. Notably, the first occurs in the opening chapter, shortly after one of Istvan’s teachers gives a speech about how species propagate themselves. The protagonist then has quite grim sex with his much older lover. Szalay has spoken of the difficultly of writing sex scenes, though the sequences in Flesh are described very matter-of-factly.

“That was the way I decided to approach it,” he acknowledges. “There is that passing reference to Darwin and that kind of thing in the first chapter, and it provides a context for the sexual encounters that follow. Obviously, his initial sexual encounters with the woman are quite fraught, uncomfortable and full of disgust. But later, he gets pretty into it. It’s not entirely grim.

“I mean, it all turns out horribly, as it happens. But there’s some positivity in those early sexual encounters. I did think the best way of approaching it was very matter of factly. I’ve mentioned, and it’s true, that the French writer Michel Houellebecq was probably a bit of an influence in how to handle that. He tells it like is – he doesn’t try to hide.

“He does it very straightforwardly. Which often offends against good taste, of course, because you can’t hope to write about these things and remain entirely on the right side of good taste. It’s a tricky ground to navigate.”

Stylistically, Flesh also has some echoes of Less Than Zero and American Psycho author Bret Easton Ellis.

“Yeah definitely, I’ve read some of his books,” says Szalay. “He sent me a very nice private message – he’s read this book and likes it. I was very honoured, really, to receive that. He’s one of the seminal figures of the last number of decades in English language literature. I know some of his books and his work is also kind of foundational. I was reading his books in my late teens and early twenties in the ’90s, and it’s very much part of my mental world, I guess.

“He had actually read All That Man Is some years ago, and I don’t know how that got into his hands. I think he posted something positive about it on social media, which was drawn to my attention at the time, and I was very chuffed to see that.”

Bret Easton Ellis

With Flesh centred on a male character prone to violence, it has perhaps bucked a publishing trend, with such novels becoming unfashionable in recent years. Mercifully, though, it hasn’t been drawn into the culture wars.

“I absolutely have no intention of getting involved in any kind of culture war,” says Szalay. “I think perhaps there is some truth, that the kind of perspective this book articulates, had become somehow unfashionable, or I don’t know exactly how you’d put it. I know around the Booker Prize, there was perhaps a slight feeling that this book might not win because of that. Obviously, from my perspective, it was great that it did. I tried very hard to ignore those kind of considerations when I was writing the book.”

Another distinctive aspect of Flesh is that for all of its postmodern qualities, it has quite a traditional narrative arc, similar to authors like Flaubert.

“Yeah, it does,” says Szalay. “That element is quite submerged. I hope it comes across as very contemporary, but yeah, in the arc of it, there is something definitely old-fashioned. The rags to riches aspect, and the social mobility, in the sense of scrambling up a ladder. That seemed appropriate, partly because in the way our societies are going, there is some kind of reversion to pre-20th century social structures of wealth and power.

“I almost deliberately wrote a story that seems kind of old-fashioned, or almost 19th century, to draw attention to that.”

When talking about old social structures, do you mean widening inequality?

“Yeah, I do. Decreasing social mobility, structures of wealth, and a gulf between the richest people and another cohort. What we would call middle class people, professionals – doctors, lawyers, people like that – are not in the same class of wealth as the very richest people, who occupy their own glittering world. That feels very 19th century to me. This isn’t a kind of PHD thesis, but it’s a feeling I have that society is coming more and more to represent pre-20th century structures.”

It’s fascinating that Istvan starts out in communist Hungary before ending up in hyper-capitalist London, suggesting both systems have inherent flaws. Does Szalay perhaps see the book’s sensibility as absurdist?

“Not exactly,” he considers. “The book obviously does start in Hungary, just as the communist period is ending. There are the first signs of that arriving, like pirated music from America and the west, and McDonalds opening up. I didn’t live there, but I visited Hungary myself repeatedly – I had family there. So that does provide some kind of background to the later part of the book, where he’s in this hyper-capitalist contemporary world.

“There’s enormous concentration of wealth in quite a small number of hands. Communism in Hungary – and across the region generally – was sort of a miserable failure. It failed to be a viable alternative to capitalism. In as much as that reference to communist Hungary has any meaning in the context of the book, it’s the sense that there isn’t an easy solution to the situation we find ourselves in.

“It’s not like being communist is going to be a solution. It’s not, because of human nature, is my own opinion of it. It just results in different power structures.”

One of the few times the largely disaffected Istvan is stirred to emotion comes with his arrival in Iraq, where he commences fighting in the war with something approaching enthusiasm. In keeping with the novel’s fatalism, it suggests violence is an inextricable part of human nature.

“Yeah, I think so,” says David. “Violence is part of the animality and physicality that the book explores. I think we have to say men particularly do have a propensity to violence, which is quite deep-seated and hard-wired. It needs to be somehow socialised, I guess – it’s something society has to deal with. It can’t be entirely wished away, I don’t think.”

Moving onto lighter matters, Hungary featured quite prominently on the Irish agenda recently, thanks to Troy Parrott’s hat-trick heroics in Budapest.

“Yeah, I can tell you Hungary was pretty depressed by that,” notes David. “Hungaro-Irish relations are at a pretty bleak pass, I guess!”

As was widely reported, following Ireland’s last gasp win, Kneecap invited Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban to “stick that up your bollocks”. Has Szalay kept abreast of political developments in the country?

“Sure I have,” he affirms. “I live in Vienna, but I still go to Hungary frequently. I still have family there, so I do follow Hungarian politics closely. There’s an election next year and it’s a big deal. It really feels like an absolutely massive fork in the road, and I think there’s a lot of nervousness in Hungary about it.”

It’s interesting that post-communism, the country has moved from one form of authoritarianism to another.

“Yeah, if that is indeed what happens,” says the author. “That of course is the fear. As of now, we can still say that Hungary is just about clinging on by its fingernails to democracy. The only thing that will really prove that, though, is a peaceful transfer of power as a result of an election. That’s why there’s a lot of nervousness around the election next year, because there’s a feeling that it will either be that – an opposition party will win and form a government.

“And then we can all say, yes, Hungary still is a democracy, because we just changed a government through an election. Or there won’t, and the fact that they’re leading so much in most polls suggests that if they don’t, something a bit shadowy is going on, and that will be quite a dark moment. So yeah, it feels like there’s a lot at stake.”

Finally, which authors made you want to be a writer?

“Joyce probably,” Szalay reflects. “He was a writer I read as a teenager and I was captivated by him. I mean, the way I write now is very different – it’s moved very far away from his style, of course. It’s not really like that, but he was definitely a writer who mesmerised me as a young person. I guess also Martin Amis, but again, I don’t write like him at all.

“But he was definitely someone who made me want to be a writer, whose use of language I found exciting. Also, to an extent, the American writers who influenced him so much, like Updike. These were all writers whose use of language captivated me, and I found it completely magical when I first encountered it. So it opened the possibilities of language.”

James Joyce

Which Joyce did you read?

“I guess Portrait Of The Artist,” says Szalay. “I remember reading Ulysses as a teenager and not really getting it, because I didn’t understand that it was basically a comedy; it was supposed to be funny. And then I re-read it 10 or 15 years ago. It was one of those things where I took it down off the shelf and started leafing through it idly, in a bored moment. But then I got so drawn into it that I basically re-read it over the next few weeks.

“I think virtually every chapter is too long (laughs). But obviously, it’s also utterly brilliant, and kind of extraordinary to witness as a performance. And it’s very, very funny in parts, and that was the thing I completely missed as a 17-year-old. It’s approach to life is sort of comical and joyous – it’s not serious at all. I mean, it is, but it gets to seriousness mostly through humour and a carnival feel.”

• Flesh is out now.