- Opinion

- 26 Nov 25

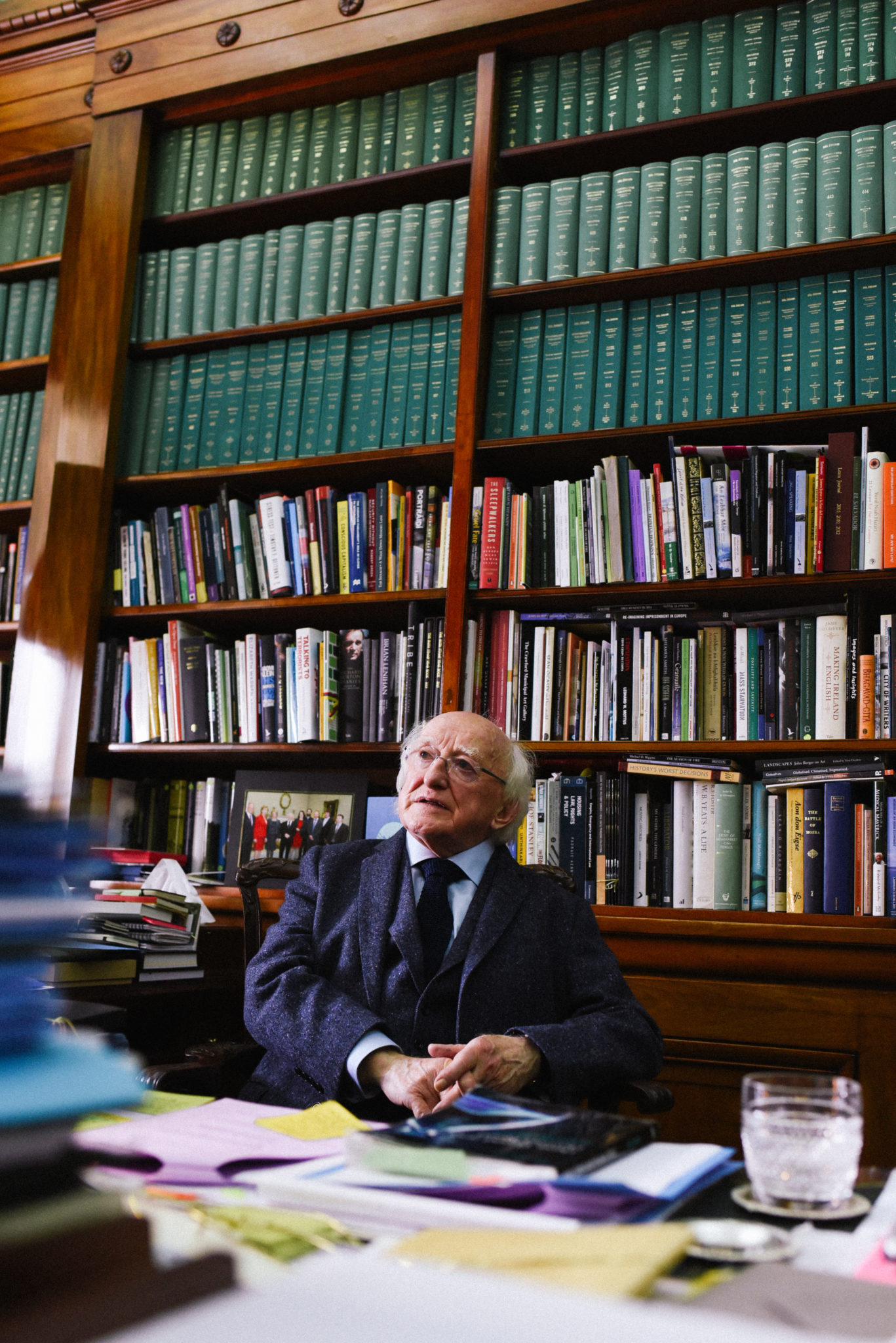

Michael D. Higgins – His Final In-Depth Interview As President: "What would have been quite dishonest is to try and invent a version of myself which isn’t real"

Michael D. Higgins served as President of Ireland for all of fourteen glorious years. From when he was first elected in 2011, he opened up Áras an Úachtaráin in an unprecedented way – winning the hearts and minds of the artistic community, and the love and affection of the vast majority of Irish people, over two inspiring terms. More than anything, on the international stage, by “saying the things he truly feels”, the President gave us all so much more to be proud of than we could ever have imagined. Here, he reflects on his stint in the Áras, his work as a poet, his time as a Hot Press columnist – and reveals his plans for the future…

It’s mere days until the vote that will signal the end of his fourteen-year tenure in Áras an Uachtaráin when we speak – and President Michael D. Higgins is looking forward to putting his feet up in the family home he’ll be returning to in Galway.

But only for a short while, as he’ll soon explain in this, his final in-depth interview before leaving office.

As has been the case since last year, the President is walking carefully today, with the aid of two walking sticks.

Moodwise, though, Michael D. is in rare old form as we share a presidential hug rather than a handshake, and he jokes about pitying the poor people who’ll have to load the contents of his packed private office into the removals van.

Among the items soon to be bubble-wrapped are the famous Colm Henry shot of Rory Gallagher and Phil Lynott tearing it up on stage together at a very special Hot Press gig back in 1982; a painting of his beloved Bernese Mountain Dog Bród, who photo bombed many an official Áras picture; and a portrait of Sally O’Neill Sanchez, a key member of Trócaire, who accompanied Michael D. on many a fact-finding mission when he was in Dáil Éireann – and who sadly passed away in 2019.

The pile of books on his desk includes Power To The People: The Hot Press Years, a collection of the columns he wrote for this magazine in the 1980s and ‘90s, which is dedicated to Sally O’Neill Sanchez; Gaza: I Spy, a photobook documenting the lives of children during the Israeli occupation; and Thant Myint-U’s Peacemaker: The United Nations And The Untold Story Of The 1960s, which the President has been devouring of late.

There’s lots to discuss, not least Michael D.’s recently released spoken word album, Against All Certainty, which reached No.3 in the Irish album charts, so – without further ado – let’s get stuck in…

Stuart Clark: I understand you’ve just watched the music video for the title track of your Against All Certainty album for the first time. With the subject matter being so personal, you must have found it quite moving.

Michael D. Higgins: I did, it’s really beautiful, the combination of the movement of the actors and the music. I particularly loved the last piece in the video. The director, Ellius Grace, did a wonderful job, as did the actors Ciarán Hinds, Olwen Fouéré and Eanna Hardwicke…

I was talking to Eanna yesterday, ahead of the release of the Roy Keane/Mick McCarthy Saipan biopic. He said he was honoured to be in the video.

That’s very kind of him. I’m really looking forward to seeing that film, as I’m sure the rest of the country is. Since becoming President, I was at a Guide Dogs For The Blind event down in Cork with Roy, who’s a major supporter of their training scheme. I first met him – and his colleague from Cork, Denis Irwin – at a fundraising lunch in Manchester to set up an Irish centre there. I was Mayor of Galway and whilst sitting with Roy and Denis said, “I studied here in the city for a long time and used to go to Old Trafford in the 1960s, when I was a big admirer of Denis Law and Bobby Charlton.” They were like, “Oh, it’s all changed now, let us show you around…” and they did.

But for the combined efforts of Sabrina Carpenter and Kingfishr, Against All Certainty would have been No. 1 in Ireland. How did the album come about?

I was invited by Claddagh Records to appear on a Patrick Kavanagh tribute and did a piece of his called ‘Stony Grey Soil’, which was recorded in this room. I was very happy with the way it was set to music (by Cormac Butler), so when Myles O’Reilly came to me with the idea of doing an album of my own, I jumped at the opportunity.

You’re coming to the end of your fourteen-year stint as President of Ireland. Is there a feeling of sadness or relief?

There’s one piece of sadness in it only, and it’s that, while sitting in this room here, I had a stroke in February 2024. I had a group out there waiting to see me from South Armagh. I was also working on a long speech about Gaza and I felt it on my left side. I was lucky because I had no cognitive impairment and I’ve recovered from most of the things on the physical side, except for my balance, which is why I use these sticks. I was gifted that there were brilliant people in the Stroke Unit in St. James’ and then the physios who came and helped me. I spent only I think eight days in hospital. I cancelled nothing and just kept going. That said, if only I could have avoided the stroke, I would’ve been ending fourteen years in a very strong way.

Did the reality of the Presidency match your expectations?

I’ve been teaching political science and sociology since 1969. I’ve published material on the writing of the Irish Constitution in 1937. There’s a great nonsense built around the Presidency by conservatives who don’t actually own up to being conservative. Which is, “Has the President crossed the line?”

Explain your thoughts on that question…

First of all, the President is directly elected by the people. Also, the Presidency is separate from the Oireachtas in the sense that I don’t have any dealings with it when it’s getting on with its business. In addition to that, there’s nothing in the Constitution that suggests the President shall be silent. Nothing at all. So therefore, I knew what I was doing in relation to all of that. Then in relation to the other side of it – I had been a Minister. I knew what it was to prepare legislation and bring it to cabinet, and the give-and-take that can involve. As President, I’m there to decide whether it’s constitutional or not and, if it is, sign it into law. That didn’t cause difficulty. Most importantly of all, I had been Vice-Chairman and President of the Labour Party. I’d visited the Socialist International, I’d a very long record in human rights.

Which proved to be very important…

I’ll just put it to you this way – when the Savita Halappanavar case happened, I was in England and was asked, “Should there not be a public inquiry?” And I said, “I hope that the inquiry will have the consequence of making it safer and better for any Irish woman in the future.” There was a big hullabaloo about it back home – but when I campaigned in 2011 for the Presidency, I published literally a manifesto on what I was seeking to do in terms of inclusion and all of that. I did the exact same thing in 2018. No one could have been surprised at my views on feminism and basic human rights.

You weren’t suddenly landing these on people…

What would have been quite dishonest is to try and invent a version of myself which isn’t real. The Presidency is the Presidency – it’s not beholden to any government department. Mary Robinson had the same difficulties I’ve had. So did my immediate predecessor. This, by the way, is not to criticise the people who came before them. I knew Paddy Hillery; he gave audiences to people he was told not to by the Department. People, for example, who are very important figures in South America and later went on to hold high office. The advice from the Department of Foreign Affairs would be, “You mustn’t meet them…” and so forth. That raises questions, really. My view is that it’s important to have an informed foreign policy. You have to inform the people.

Michael D. Higgins with Mary Robinson

By any standards, it was a hugely successful Presidency – taking the first seven years for a start, was there an outstanding moment for you?

Very early on, I returned the State visit to the United Kingdom. It was an interesting one. You had the question of why had Sinn Féin not shaken hands with the Queen when she visited Ireland, and would they shake hands if I returned the visit? I was involved in the talks that were trying to smooth that. It included a meeting with Martin McGuinness and Gerry Adams. You’ll have to wait for my biography for the minor details, but I did say to them, “Look, if you were sensible you’d have shaken her hand last year when she was in Ireland. Just sort your head out, before you ask me what I’m doing.”

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth and the now King Charles very clearly understood that we were meeting as two heads of State. This had been in the Queen’s speech when she visited the Garden of Remembrance here. I was the first Irish President to be invited to speak to the Houses of Westminster, which was hugely symbolic. I worked very hard on that speech. It’s where I used, “Ar scáth a chéile a mhaireann na daoine: it is in the shadow of each other that we live.” What was particularly moving, as we came to the end of the visit, was the meeting I had in Coventry with the older Irish who’d emigrated in the 1950s.

A few years ago, I visited a drop-in centre in London for homeless Irish people, many of whom were in their 60s and 70s and for various reasons had become estranged from their families back home.

A lot of them were working on the lump, there, with Irish contractors. Because they didn’t have a sufficient number of stamps, they went on to have trouble with their pensions. When I became a TD and then a Minister, I’d contact HM Revenue & Customs in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne on some of these people’s behalf, trying to find out the years they were there and what the name of the employer was. The person who used to help me with that was Hilary Benn. He knew there’d been a relationship between myself and his father, Tony Benn, and his mother, Caroline, so straight away there was a great rapport between us. He had lunch with me here not long ago.

Am I correct in saying that members of your own family went to England, for economic reasons?

Yes, my sisters emigrated to Manchester in the 1950s. How they ended up there was that British Rail put an ad in Irish newspapers saying they were hiring for their restaurants and cafeterias. They provided accommodation and free passage from your nearest railway station. They were very difficult circumstances, because we were splitting up as a family.

I myself took the boat over to Holyhead for the summer and got the connected train that delivered you into London Euston station at about 6.30 in the morning. I worked as a barman and then a waiter. I was in this hotel when the Evening Standard newspaper brought a hugely negative thing out about Ireland. I wrote in (to the editor) asking, “Who do you think are building your roads and running your hospitals?” That was my first published letter and the owner of the hotel I was in, in Alfriston, Sussex, Mrs. Hicks, said, “Mr. Higgins, if you wouldn’t mind not giving the address of the hotel in your correspondence with the papers.”

But this, ‘No Dogs, No Blacks, No Irish’ thing was very real. To finish up about Sussex; while there, I also wrote my first long piece for an Irish newspaper, The Sunday Press. It was because I was very near Brighton and I wrote about the Mods and Rockers. In the lanes of Brighton, there were fantastic second-hand clothes shops, so when you came back to Ireland in the autumn – I ended up spending three or four summers in England – you’d look very cool in all the Mod gear, without it costing you a fortune.

What would you consider the defining moments of your second term to be?

It might be useful for me to explain what I think connects the two terms, which is my interest in memory. In 2011, you were coming into the period that had 1916 and the War of Independence commemorations. I wanted to have an ethical approach to what we were celebrating and what we were recalling. It wasn’t just about people marching up and down. We were interpreting what took place. The biggest thing in that first seven years of the Presidency was I had the relatives of all the people who were involved up here in the Áras. I gave a number of speeches on the lost opportunities for peace in the 1918 election. I’d already participated in a radio programme on the Citizens’ Army, the Great Lockout, William Martin Murphy and so on. I was saying, “We must get all sides of this in.”

Michael D Higgins at Áras an Uachtaráin. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Which links to your second term…

When we came to the second seven years, I assembled a thing called Machnamh, which translates as ‘reflection’. My point was to make sure that people and things that hadn’t been included in the previous historiography would now come into it. Women, the formation of the new State, the role of the Church, the domination of the land… I had to deal with something that is very painful in my own psyche, which is the fact that my father was anti-Treaty and was released from Hut No. 3 on the 21st December, 1923. His brother was also in the National Army and both had been in the War of Independence.

Inevitably, class was an issue in all of this…

The biggest difficulty in Irish historiography had been dealing with social class. 1923 is the terminating point of the division of a lot of the estates in Ireland. The people who were released didn’t get their jobs back. Many of them emigrated to America; they were ill-treated in relation to pensions; they wouldn’t, of course, have got any land. So, what is the character of this Irish State? I tried to address that through the use of memory, involving people from the North, from the South and from abroad.

What none of us knew when your second term began in 2018 is what lay ahead in Israel and Gaza. As far back as June 1988, you wrote a powerful piece for Hot Press titled Gaza And The West Bank: A People Set Apart, which highlighted the post-World War II wrongs done to the Palestinian people. Can you tease that out?

A question you need to ask is, “Was Palestine an empty space?” They were going to make provision for what they thought was eight million people of Jewish faith who’d suffered as a result of the Second World War – and correctly so. But how were they to deal with the Palestinians who’d been there for generations, some of them as Bedouins, others as farmers and fishermen and so forth?

They refer to them in all the documents as ‘Non-Jewish’. When I stood in the West Bank I’d ask (Israelis), ‘Do you not think of the people of Palestine?’ and they’d go, ‘What? Who? There is no Palestine. There’s just Judea and Samaria. There are no Palestinians, they’re Arabs’.

For some people, there will never be a Palestine, just Arabs who are their enemies. From a philosophical perspective, I said in one of my speeches that if we don’t deal with the Palestinian issue, the human species is actually a failed species. We’ve put the planet itself in danger.

Michael D. Higgins protesting against the first Gulf War

As President you’ve had to express yourself with extreme care. Are you looking forward to the shackles being removed when you leave the Áras?

It’s a good question to ask me. I’m struggling with how to answer it myself! I expect that I’ll be speaking with more freedom. I’m certainly not short of invitations. If I can get to it – and I’ve kept an enormous number of notebooks – I’d like to deal with some basic philosophical issues. One of the biggest challenges to humanity is technology. The ownership and non-accountability of the global technological sector is going to be a powerful new source of domination, repression and suppression. The audacity of Elon Musk and others firing it in people’s faces. His influence on politics is extremely dangerous.

Also the technocratic elements among some parties – are you talking about democracy or are you talking about efficiency? If you say that efficiency requires unaccountability, unrestrained wealth, no regulation and so forth, how much are you willing to sacrifice? The answer is that in the western world, people are willing to sacrifice a lot. Of course there are restrictions on freedoms in countries like China, but what if you don’t know it’s happening to you? The scrabble for resources in Africa at the moment is very much about who controls the technocracy. Why? Because that’s the fastest conversation you can have with the elites who are open to corruption.

It’s fascinating; with the right at the moment, it’s like a virus. You need to confront this new rabid stuff by asking, “What is it precisely you stand for? What are you against? What is your end point?” There are actually political parties that are willing to let their membership go, in order for a technocratic advantage. In other words, they’ll say, “What’s important is not how many members we have or not what the members want. It’s who among the oligarchs do we have access to?” That’s why the media, in many cases, writes about how so-and-so will be enormously valuable because they have that access.

Sabina has been an extraordinary ‘first woman’. How important has it been having her at your side these past 14 years?

Yes, one of the things to remember is that this has very much been a shared experience with Sabina. Yesterday she was running Latching On, as she has done every year we’ve been here, which is promoting breastfeeding. We had around a hundred and fifty women who are breastfeeding, midwives and other experts, advocacy groups and so forth.

The women in the institutions, who had those awful experiences, also came up and visited us. Walking outside, they told us their stories. We knew of the Magdalene laundries because the woman who wrote the original play about it, Eclipsed, was a friend of ours. I also remember the wonderful people from the Rare Diseases Families who came to the Áras.

There’s something in one of my speeches which I think is quite important. I said, “It really should be a Republic of Vulnerabilities.” What I meant by that is a real Republic is one where every person is encouraged and supported to participate fully and where every person and community is treated with dignity and respect.

Sabina and Michael D. Higgins at Áras an Uachtaráin

What’s next for Michael D. Higgins?

I’m looking forward to a bit of a holiday, and then I’m going to continue my work in areas such as food security in Africa. I’ve two or three writing projects. Before becoming President, I was talking to the late Michael O’Brien of The O’Brien Press about me doing a book on the 1930s, which is a period that really interests me. You had censorship in Ireland, fascism, the Spanish Civil War, the opposition to jazz and dancing… I left that aside. Then, I was writing a separate one on the relationship between land and respectability. I believe that land is the dominating thing in not just Irish society but in numerous other countries.

It sounds like you’ll be busy!

Bernie Sanders has also asked me to become a fellow at the Sanders Institute and I’ve said ‘Yes’ to that. I’ve met Bernie two or three times. I so much admire what he’s trying to do – which is to bring new thinking into the Democratic Party and in turn save America, which is an enormous task. I think America is very damaged internationally. I think it’s very damaged in terms of its own social cohesion at home. It’s also going to create a huge gap in the geopolitical framework.

Bob Geldof has spoken about the hundreds of thousands, who’ll die as a result of the US abandoning its foreign aid programmes.

Geldof is right about that. The cut in aid in Britain is about £800 million. The cuts in the United States are many multiples of that. I was asking President Ramaphosa about South Africa. They’re generally in better shape than most, but have a real problem accessing antiviral drugs for HIV/AIDS. You had some people from the southern United States getting three days of a hearing from the Ugandan parliament in relation to restricting the rights of LGBTQ people.

Michael D. Higgins talking to Niall Stokes and Bob Geldof at the Hot Press 40th Birthday Covers Exhibition

We were very excited last year to publish Power To The People: The Hot Press Years. There’s a wonderful photo of you presenting Joan Baez with a copy when she came over for the Dublin premiere of the Joan Baez: I Am A Noise film. Had you met her before?

During the 1980s, I did a number of things for a group in America called Artists Call – Susan Sarandon and Ed Asner were running it. I participated in an event of theirs in New York, which was very interesting, because Allen Ginsberg had become respectable and was in charge of bringing all these poets together. That’s when I would have met Joan Baez.

You’d encountered Ginsberg before that, hadn’t you?

Yes, I originally met him back in 1967 in Indiana. That time he was sitting on the ground, with people and a beautiful whiff of smoke all around him. Later on, he came to Galway (for the Cúirt International Festival of Literature), his fee being a tweed suit. People don’t know this, but he was buried in that same tweed suit.

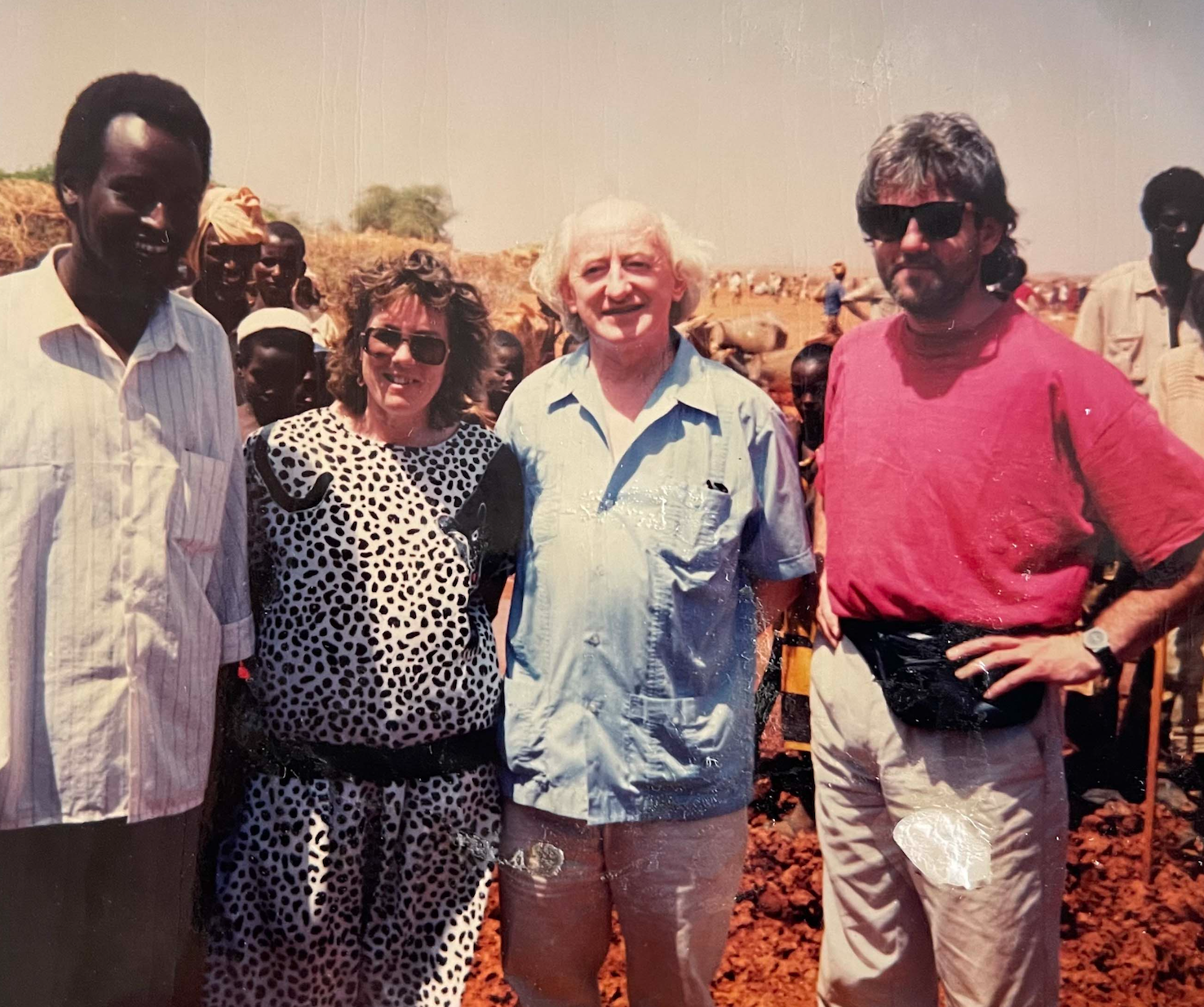

Power To The People is dedicated to Sally O’Neill Sanchez, who was your wing-woman when you went on many of your fact-finding trips in the 1980s and ‘90s.

Sally was the person who was with me when I went to investigate the massacre of civilians in El Mozote in El Salvador. The New York Times and The Washington Post then took it up. I went to the United States to lobby for the ending of arms sales to El Salvador. Teddy Kennedy proposed the resolution and it was passed by 84 votes to 12. I remember Sally being thrilled by that. I also helped Trócaire with the documentary they did in Somalia, during the famine. We were in the Middle East together, Colombia and Honduras as well. Sally died six years ago in Guatemala. She, and her colleagues, were travelling and their jeep fell into a gorge. She was a remarkable person and I miss her very much.

Michael D. Higgins on a 1992 visit to Mogadishu with Sally O’Neill Sanchez and Gerry McColgan

I remember you desperately trying to find the only fax machine in some far-flung corner of South America or Africa in order to file your Hot Press column.

The fax machine was the big technological innovation of the time. I don’t use a typewriter or word processor at all – I’m writing everything longhand, so Niall (Stokes, Hot Press Editor) would be getting these reams of paper from me with strange hieroglyphics on them after I’d located the communal fax in wherever I was! Then, there were the photos. I remember Sabina accompanying me when I was in the Sahara. She’d brought the one good Olympus camera she’d ever had, to take them for me, and sand got into it. That was a point of discussion for a very long time!

The last time we spoke, you mentioned meeting Leonard Cohen as being one of your all-time cultural highlights. Has anything matched that since?

I loved Leonard; there was such a strong poetic instinct in all of his lyrics. Very shortly after I’d arrived in the Áras, he played a gig in Kilmainham which I went to with the Secretary-General of the Department of Foreign Affairs at the time, Adrian O’Neill, and his wife, who were also interested in Leonard Cohen’s work.

I was new to all this business of having security with me, so coming out, a big group of us were walking along, when I saw this man sitting there who I realised was Leonard Cohen. I said “Hello” to him, and Leonard asked me to join him for a bowl of chicken soup. I said, “That sounds good” and we talked about him loving being in Ireland; me not being very long at this President business; and particular pieces of his that I love such as ‘Anthem’.

Those lyrics – “Ring the bells that still can ring” and “There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in” – are incredible. My favourite, and I told him this, is ‘Alexandra’s Leaving’. It’s an extraordinarily honest, beautiful and emotional piece. And, yes, I realise I’ve totally ignored your question!

I’m a Leonard Cohen nut myself, so I’m delighted to hear that story in greater detail! We both had the honour of being at Shane MacGowan’s 60th birthday bash in the National Concert Hall. Was that a good night?

It was a great night! People concentrate a lot on some of the exotic moments in Shane’s life, but the beautiful compositional strength he had is something which to me is very, very important. To be able to see the essence of things, like Shane did, is a rare and precious gift. When I look back through my life, yes, there are inspirational people in politics and others who I admire, but the people I’ve actually wanted to spend nights with were heavily in the artistic community. I got an energy from that, long before I became a minister.

Michael D. Higgins attending Shane MacGowan’s 60th birthday bash with Johnny Depp and Victoria Mary Clarke

Niamh Algar – who’s currently starring in Sky Witness’ The Iris Affair – said to me recently that the catalyst for all the Irish BAFTA, Emmy and Oscar wins of late is your re-establishment, as Minister for the Arts, of the Irish Film Board in 1993, which transformed the TV and cinema industries here. Does that make you feel proud?

The 1980s was a hard time for the arts in Ireland. Before I became Minister for Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht, I was Chairman of the Galway Regional Arts Committee, when it hired its first Arts Officer. One of the things we did was put a piano in a horse-box, which went to places where people had never heard piano live before.

Sabina and I were agitating for there to be floors in primary schools that children could dance on, and for dance to be made part of physical education, which elicited a famously dismissive letter from the Department of Education who said, “Dance has nothing to do with physical education!” In fighting these different battles, I made close friends with people from right across the arts community, who I was able to call on in 1993, when I became Minister.

The big decision stuff – like the Irish Film Board, TnaG and training people for jobs in the audiovisual industry – was done in the first six months. There was still a High Art vs Community Art debate going on in the newspapers. We were pitching in and saying, “Look, given the opportunities everybody can be creative” only for certain people to tell us, “No, that’s nonsense!”

Somebody who was very important in all of this was Chris O’Grady. He was secretary to the study group which government had set up to consider the employment potential of the film industry. Albert Reynolds, who was Taoiseach at the time, handed me their report and said, “Michael D., this is your thing now.” After I’d taken the report away and studied it over Christmas, he asked, “Could you put a figure on this?” I said, “With a commitment of between ten and twelve million we can get much of it going.” Chris’ great advantage is that he’d worked with Charlie Haughey and the Revenue Commissioners and therefore knew how to approach the idea.

And then a Hollywood superstar entered the picture…

We only had four people in that section, but when we heard there was trouble brewing in Scotland for Mel Gibson and Braveheart – the ground there wasn’t suitable for all the horses they had for the big battle scenes – I certified it for investment through our new (Section 481) model. I went to Santa Monica and held a press conference at which I said, “I’m expanding the tax relief and it’ll be there for so many years.” All sorts of film people attended and, fair play to them, they all came to Ireland and on we went. Anyway, I said to the Minister of Defence, David Andrews, who I worked really well with, “I know people who can take care of the horses but they also need a load of extras.” And he arranged for members of the Army Reserve to take part. They went in soldiers and came out warriors!

Michael D. Higgins with Mel Gibson

You played hard ball with Mel Gibson, didn’t you?

Our basic demand to Gibson was that we had an Irish assistant to the crew he brought in at every level. I had a handbook that David Puttnam (producer of Chariots of Fire, The Mission and Midnight Express) had helped prepare, which was everything you need for the making of a film. Gibson said, “Is that it now?” and Chris O’Grady went, “There’s only one piece left – we want an assistant to yourself!” And he said, “Okay, I’ll do it!” Everyone who came in was told, “Every skill you need will be here.” Where I’d like to have gone with it was a system called Mondiale, which would’ve been an alternative to people like Rupert Murdoch. I was going to take the film archives of all different countries and promote them internationally. I had meetings in both Chile and Argentina, which has one of the biggest film schools in the world, but I was out of office before I could advance it.

You were at Pope Leo XIV’s inauguration in June. What are your thoughts on the statement he made about how being Pro-Life should extend to treating immigrants with kindness and respect?

Leo XIV was enormously gracious at his inauguration. We were in a very crowded environment, and he rose to come and meet me. I think he’s going to be very good. He was something like forty years in Peru and is very well informed. He’s such an atypical American bishop.

That might be very important, the way things are evolving in America…

Let me just say something about the different America we’re talking about now. When I was calling for the United States to stop the sale of armaments to El Salvador, the Council of American Bishops were running an asylum and refuge programme for Salvadorians. The right-wing cardinals in the US now are very much a product of American capitalism. That is why it’s outstanding, and so important, that Leo XIV is there. He’s a better scholar and has more experience of the world than any of the others who were contenders. One thing I don’t pretend to understand is these fundamentalist Christians and evangelicals, who are shouting and roaring at Trump’s rallies. I don’t know how that has anything to do with Jesus of Nazareth. It’s based on fanatics embracing a fiction.

Michael, thank you for today and the other times yourself and Sabina have invited Hot Press into the Áras. We’re delighted that you won’t be quietly riding off into the sunset and wish you good health.

What I’ve said so many times publicly is that when talking about, say, the El Mozote massacre, there was no place else that would print any of that material, so ‘thank you’ to yourself and Niall and everyone else at Hot Press.

Copyright Abigail Ring/ hotpress.com

RELATED

- Opinion

- 11 Sep 25

Reactions pour in following the shooting death of Charlie Kirk

- Opinion

- 11 Sep 25