- Music

- 03 Jan 26

Miranda Sawyer: “I remember Alex from Blur saying to me, that if wasn’t for Damon, he and Graham would be sat at home picking their noses"

Journalist and author Miranda Sawyer talks about her collaboration with Blur’s Dave Rowntree on the photo book No One You Know, which offers a fascinating inside look at the band’s early years. Also up for discussion are ’90s music journalism, pop feuds, Stormzy, Lily Allen.

Drawing from the archive of Blur drummer Dave Rowntree, the photo book No One You Know documents the Britpop heroes’ early days, as they make their first album Leisure, head out on the road, and try to make their mark on the wider world. It provides a fascinating insight into the band’s early years, when superstardom still lay a long way in the future.

To edit the book, Rowntree drafted in as editor Miranda Sawyer, the journalist and author who’s enjoyed a long association with the band, interviewing them numerous times and even writing the sleeve notes to their career-spanning 2012 boxset, Blur 21 (one of the handful of albums I’ve ever given full marks in the review pages of Hot Press).

Did Sawyer know the band right from the early days documented in the book?

“Yeah I did,” she reflects from London. “Basically, what happened with the book was I’ve known Dave since around 1989. So he got in touch and said, ‘Look, I’m meant to be doing this book, but I’m not. So I just need someone to tell me to do it!’ (Laughs) And I was like, ‘Fine, I can do that!’ He’d written most of the intro, but not all of it. Quite often, it’s just encouragement. I was like, ‘Yeah, that’s good, maybe expand on that.’

“But he had these pictures, which he’d found after a really long time. They were in this metal box he’d thought he’d lost, and then he found them. He showed me them all and there were really a lot. Basically my job was to say, ‘Stop putting landscapes in, and put in the fit pictures of Damon and Graham, are you mad?’ So I feel like fans can thank me for that.”

Sawyer first got to know Blur in the early ’90s, when the team from Smash Hits – where she worked as a journalist – would go drinking with the band and staff from their label, Food, who were based around the corner in London’s Golden Square. Right from the off, she could see how driven frontman Damon Albarn was.

“I know people who don’t like Damon at all,” says Sawyer. “I really like Damon, he’s always been absolutely brilliant to me. But he had a rocket up his arse. I remember Alex from Blur saying to me, that if wasn’t for Damon, he and Graham would be sat at home picking their noses. It’s the same with Noel Gallagher or Thom Yorke – you need someone who really wants it, and believes you can get it. And Damon is incredibly competitive, he admitted that to me in an interview.

“I was like, ‘What is wrong with you?’ (laughs) And he was like, ‘I’m really competitive.’ He acknowledged it to me, particularly with other men in the arena of music. There was a thing that happened with Damon. He could be quite spiky – I mean so we could we all, we were all loonies – but even though he had a bad time, and panic attacks and everything like that, there was something in him that relaxed when Blur became big.”

Miranda Sawyer

Miranda SawyerSawyer further considers how vital it is to have that intense commitment.

“It’s a really important thing,” she continues. “Cos a lot of bands are absolutely brilliant, but they just want to stay in the studio, maybe they’re not sure about playing live. They don’t really want their photos taken. There’s nothing wrong with that, music is for everyone. I personally believe there’s something really brilliant in playing music, even if you’re not, in inverted commas, ‘good’. I don’t care.

“Especially you know from Irish and English bands, in particular, they’ve got a thing where they can go, ‘You know what? Fuck it, we’re just gonna do it.’ It’s like the punk attitude: ‘I don’t care if I haven’t played bass before. I’m gonna play bass now and we’re gonna be great.’ I completely believe in that.

“I once interviewed Stormzy, who’s matey with Ed Sheeran. I said, ‘That’s so weird, why are you making tracks with Ed Sheeran?’ And Stormzy said, ‘Because I met him and I saw the same thing I had.’ Which is like, ‘I want to be massive and you’re not stopping me.’”

ART SCHOOL TRADITION

One of the most compelling aspects of Blur, and their Britpop peers in Pulp and Suede, was the way they wrote about growing up in boring suburbs and provincial towns, always with a subversive edge. It’s an approach not usually favoured by Irish bands – with the notable exception of Ash – who tend to come out of a more folk-based lineage.

One of the theories I’ve harboured for a while is that the aesthetic difference is largely attributable to the English art school tradition, which we don’t really have in Ireland.

“Yeah definitely,” says Miranda. “It’s interesting, because one of the things I really respect about Irish culture is the respect it has for music. So that’s what I was kind of talking about. Obviously, there are absolutely brilliant musicians in Ireland, but it’s like one singer, one song. Step up, do your song, you know what I mean? It doesn’t matter if you’re shit – step up and fucking perform!

“Then obviously, if someone follows you who has a voice like Sinead O’Connor, you’re fucked. It’s a thing everyone does and I really respect that. But I think you’re right – the English scene is different and art schools are really important. But also, because of the nature of England, it’s got quite a lot of immigrants. And I genuinely believe that the pop music scene is so good because of that.”

She teases out the idea further.

“Quite often, your parents might be immigrants,” Miranda continues. “Like, obviously The Beatles. It’s often actually Irish immigrants. And then you have Stormzy or Dave – or fucking anyone. It’s nearly always they’ve got parents who come from somewhere else, and then they’ve arrived in – you could say Britain, but it is mostly England – and their parents go, ‘You’ve gotta work.’

“There’s a work ethic, but there’s also the tradition, which is very strong in many cultures, of music. With Ireland it’s incredibly strong, Ghana, Nigeria, Jamaica – these are really strong musical societies. Then they’re thrown into this kind of weird environment of England, where everyone’s squashed together and a bit spiky. Pop music is what we’re good at, and I think that’s where it comes out.

“But I do agree that art schools, especially with Britpop and punk, were really important. Because they allow you to meet other people and experiment.”

As well as her journalistic work, Miranda also comments on music and pop culture on the excellent podcasts Talk ’90s To Me, Bandsplain and We Have Notes. On the latter, she recently discussed Lily Allen’s headline-grabbing West End Girl, undoubtedly one of the albums of the year.

SPECIFIC AND RAW

“I got sent the album early, in August or something,” she notes. “She was very worried about it, as one might be. I think she felt it was like a bomb that she’d made – does she let that bomb off or does she not?

What was really funny about it was, when I got the album, I did exactly the same everybody else did. At the time I thought it was just me, but I listened to it over and over.

“So much so that the record company cancelled the stream, cos they thought I was selling it on! Not everyone, but women of a certain age have been doing that over and over. It’s very interesting to be as specific – I’m aware she says it’s fictionalised, but it’s very specific as to her emotions, rather than the scenarios. It’s how she is. It’s specific and raw, but it’s all so pretty – sometimes it sounds like a Disney film.”

The album was certainly very bold in its conception and execution.

“To be that precise, it’s a very interesting situation,” says Sawyer. “We’ve had lots of strong women artists over the last few years, like Charli XCX and Billie Eilish. I went to see Lorde recently and she was amazing. I didn’t even think I was a fan, I just took my daughter. I thought, god, she holds a huge audience in a very intimate and low key way.

“Especially, how a female artist can be sexual without being a cliché, it’s really hard. I thought she was incredible actually, really great. And there’s so many artists like that who’ve I’ve really enjoyed. I went to Primavera this year and the headliners were Charli XCX, Sabrina Carpenter and Chappell Roan. I found that really heartening.”

One of the aspects of West End Girl I found most interesting was that, in the years prior, Allen seemed to have drifted into being a media figure who commented on the culture. Whereas, the album offered a reminder of what a brilliant pop star she remains.

“Absolutely,” says Sawyer. “She hadn’t done it for seven years, and previously to that album, she was trying to make music. I interviewed her about her podcast, and she was saying, ‘I’m finding it really hard to make music, I just don’t know what I’m doing, it’s not working.’ And that’s quite interesting because – and this is me extrapolating – but I do think this. She was in a kind of difficult relationship, where it’s hard to get hold of things.

“So everything around her was a bit foggy, and when she was making her own art, she wasn’t able to get to the point where she knew it was any good. It’s really interesting to me that once that relationship had ended, then she was able to get back to the thing she’s really good at. I’m not saying she’s not a great actor, but we want her onstage doing music, don’t we? She’s a great podcaster, she’s a great actor, but actually that’s what we want.

“I’m certainly not saying that relationship was entirely toxic, because I don’t think any relationship – unless you’re incredibly unlucky – is entirely toxic. That was a love relationship, they loved each other, it fucked up. But while she was in that relationship, her main art was not flourishing, and I find that quite interesting.”

In 2024, Sawyer also revisited the Britpop era in her superb book Uncommon People, which drew on her experience writing for magazines like Select in the ’90s. How does she see the change in music journalism now, when it no longer has the same comedic flair or biting reviews?

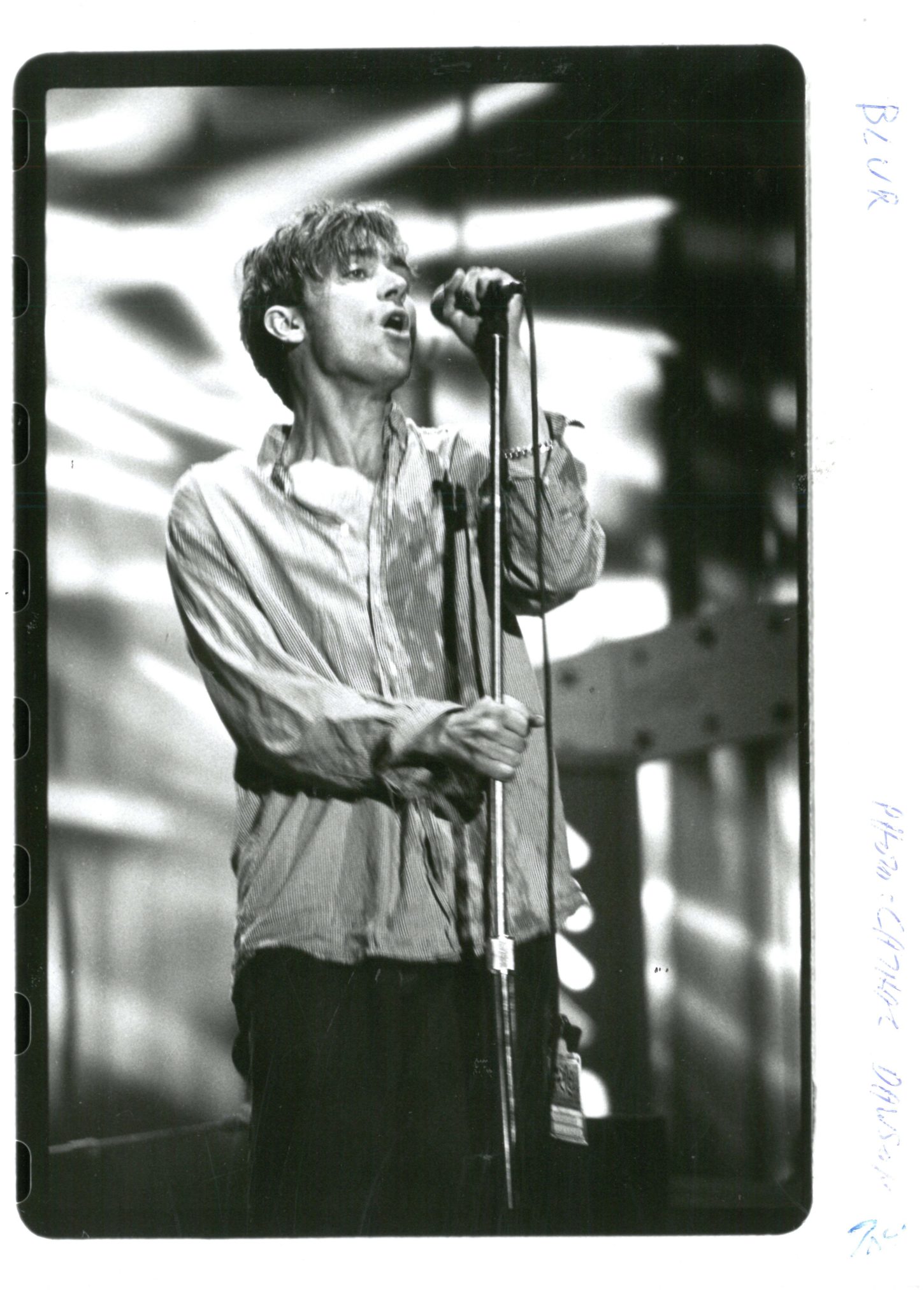

Blur by Cathal Dawson

Blur by Cathal DawsonLAST HOORAH

“We didn’t realise it, but we were working within this huge, last hoorah of the music press,” she says. “There was an architecture of that time that has changed. Back then, there were really cheap rents in London – I never paid more than 50 quid a week, people were paying less than that.

“Also, your flat was shit, so you had to go out. There was no internet. If you wanted to shag someone, you had to leave the house, you couldn’t just go on an app. If you wanted cheap drink and friends, you went to gigs. So that was one kind of structure. There was money in the music industry from CDs, which trickled down to all the indie labels, which was really important.

“And you’re right, there was a really healthy music paper scene, all the way through to NME and Melody Maker.”

However, as Sawyer notes, there were considerable negatives too.

“When I read a lot of it – particularly NME and Melody Maker – some of what they wrote I thought was pretty awful actually,” she says. “There was some terrible, appalling sexism. I was really shocked. I was lucky to work for Select, where there was a lot of men who worked there, but they weren’t sexist. But definitely some of the writing in the NME, I was like, ‘Oh my god.’ About Polly Harvey and Shirley Manson – it was just absolutely shit.”

On a lighter note, one thing the era did have going for it was the often hilarious slagging between bands.

“I know, bring back the pop tiff,” says Sawyer. “I’m very up for the pop tiff between Taylor and Charli. And I’m on Charli’s side, obviously!”

• No One You Know is out now. Talk ’90s To Me and We Have Notes are streaming now on all platforms.

RELATED

- Music

- 27 Apr 25

10 years ago today: Blur returned with The Magic Whip

- Music

- 30 Sep 24

Oasis announce North American leg of reunion tour

- Film And TV

- 09 Sep 24