- Music

- 21 Jun 25

Celebrating the genius of Rory Gallagher: "He blazed a trail out of Ireland, showing us all that it could be done"

Thirty years on from his untimely death, it’s clear that, through his extraordinary albums and live performances, Rory Gallagher has left a towering musical legacy.

Rory Gallagher died 30 years ago. Even as I write that, it seems difficult to compute. Thirty fucking years is a long time and yet the memories of the man are still fresh, strong, unforgettable.

Seeing him on stage with the mighty Taste. Watching as he hit the heights over those first two albums, Taste and On The Boards. Even now, I can hum the riffs and sing the opening lines of ‘Blister On The Moon’, ’Sugar Mama’, ‘Born On The Wrong Side of Time’, ‘What’s Goin’ On’, ‘It’s Happened Before It’ll Happen Again’ and the dreamy, Cream-like ‘On The Boards’, with its gorgeous clean guitar tone, and Rory blowing evocatively on sax.

If you want to know just how extraordinarily brilliant Taste were, dig out the Taste: Live At The Isle of Wight movie. It is one of the most remarkable records of a live performance we will ever be treated to.

Nowadays, all manner of trickery is used to shape, bolster and frame live shows. That’s fine. It can deliver elements of marvellous theatre and, on occasion, heightened musical magic.

Back then, it was down to a pen, a piece of paper and a slice of gaffer tape to stick the set-list to the floor. If you could afford a biro..

But this is one of those moments when you realise the meaning of the old adage that less is more. There’s just the three boys out there: Rory Gallagher, Richard McCracken and John Wilson. Rory, we know, is a guitar genius. But all three are superb musicians, and you can tell right from the start that there is something special in store.

They had been together for about two years by the time they played the Isle of Wight, at a festival that also featured Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, The Who, Joni Mitchell. Sly and The Family Stone, Miles Davis, Leonard Cohen, Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Kris Kristofferson, and a football squad’s worth of other well-known names – Procol Harum, anyone? – from then and now. For many, Taste were the standout performers that infamous weekend.

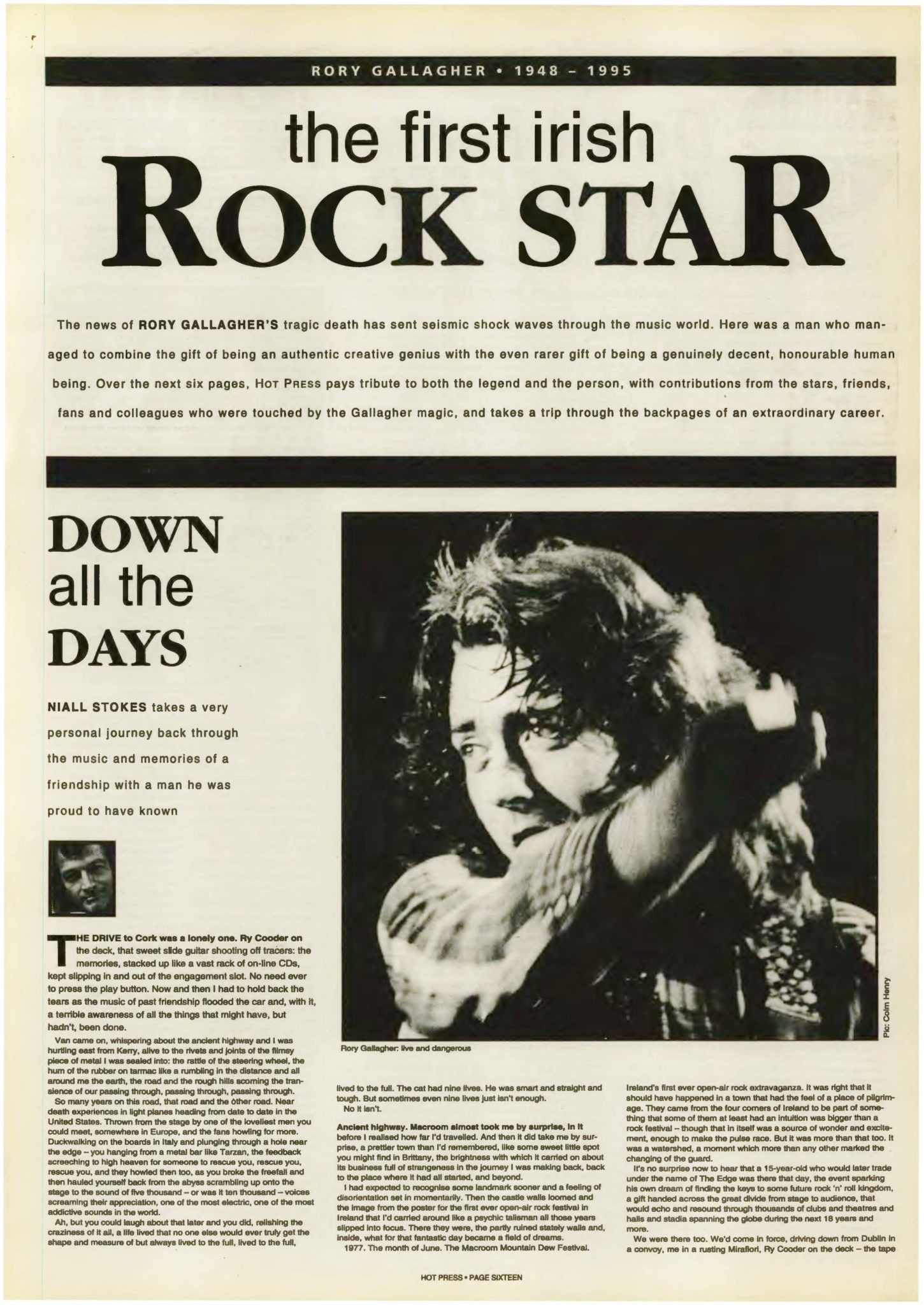

Watching the film, there are controlled ebbs and magnificent flows. Rory stalks the stage like a demented musical conjuror, the notes sweeping and swooping, strings bent wildly and then allowed to revert to the axis, slashed with the right hand, sprinkled with the left, then via his favoured slide, wailing and crying like there was no tomorrow, which there very well may not be the way things are going...

He looks around. McCracken and Wilson feed off his energy and momentum. They are listening. Watching. Tightening the beat. Easing off. Frowning, smiling. Slipping in counter-rhythms. And Richie on bass finding melodic foils to the main man’s main-lines. It is all happening in real time: thrilling, mind-melting, inspiring. There’s a story that Jimi Hendrix was asked “What does it feel like to be the best guitar player in the world?” To which Jimi replied, “I don’t know, ask Rory Gallagher.”

It hasn’t been possible to confirm this exchange with documentary evidence, but having watched this outrageously incendiary statement of intent, with its rock ’n’ roll heart, blues power, soulful purpose and cathartic, shamanic immersion in the now, you can imagine that Jimi might well have doffed his black wool felt Westerner hat in acclamation.

ULTIMATE STORY

We talked, inside Hot Press and out, about what Rory album we should cover in our Hot Press Classics podcast series. There were arguments for Calling Card, which is packed with Gallagher gems.

The title track is a classy, mordant, fatalistic blues with its gorgeously everyday opening couplet.

“Well, the rain ain’t fussy ‘bout where it lands / It’ll find you hiding no matter where you stand,” Rory complains. We’ve all been there.

‘Moonchild’ is another beauty, a song of unrequited love with, as its centre-piece, a plea: “Tell me why you look so sad / Time slips by like grains of sand / Just put your future in my hands.” There’s no sign by the end of the song that the man’s wish has been granted. “Just give me a sign,” he begs, “and I’ll shows you my plan.” But the sign it never cometh.

In an interesting twist on Rory’s fascination with the hard-boiled school, ’Secret Agent’ turns the G-man’s customary take on woman-troubles on its head, with our narrator warning off a Private Investigator who is keeping him under surveillance at the behest of a jealous lover. “Secret agent, secret agent,” he clamours, “Won’t you please heed my advice / You crossed me once, don’t cross me twice…” And then the throwaway line tagged on at the end: “I’m gonna cut you down to size.”

‘Country Mile’ is the ultimate story of an outsider, who revels in the sheer transience of things: a drifter going at breakneck speed to escape the cruelties of convention, as he tries to out-race the bus. “Well I was born on the side of a road,” he recounts, “A gap in the hedge / Did you hear what I said? / Born in a house with no slates / But I wouldn’t switch / I didn’t have a stitch / Always been out on a limb / I’ve been hard to mend / Like a kick in the shins ...” The lines are drilled out, sometimes two at a time to pack the pictures in.

There were others who made the case for Top Priority which is a personal favourite. It opens with ‘Follow Me’, a blistering song of hope and longing – with a stronger Irish flavour in the melody than is customary in Rory’s work – that matches great guitar playing with an edge of despair. “Won’t you follow me where I’m bound / Time’s for borrowing now / Won’t you follow me, time is tight / Before things swallow me down.”

Almost everywhere, there are glimpses of doom, but the track is leavened by the addition of an electric sitar – apparently borrowed from Pete Townshend of The Who – that adds sonic intrigue and adventure.

That’s followed by ‘Philby’, probably my favourite Rory song, and certainly the one I’ll most often sing and play at home when there’s a guitar to hand. In making the link between a spy’s outsider condition and his own, Rory captures with brutal insight the twilight zone in which the travelling or touring musician is sunk for so much of the time. “Now ain’t it strange I feel like Philby,” the narrator muses, though you know this one is personal, “There’s a stranger in my soul / I’m lost in transit in a lonesome city / I can’t come in from the cold.”

If he is out in the cold in ‘Philby’, it’s another story entirely in ‘At The Depot’, where he’s doing what the Irish navvies did for decades in London, and other parts of the UK, hanging around on the corner looking for work, even for a day. It is Rory, always on the side of the working man, the everyday seep of despair and anger just below the surface. “Well, I’m hanging around the corner, boys,” he sings, “Holding up the wall / Feeling kinda sloppy, waiting for a call / Running out of patience, running out of cool / Don’t turn on the radio, I don’t want to hear the news.”

The prospect of hitting Fat City and making it with the woman of his dreams is dangled – but you get the sense that it is worse than a desperately forlorn hope.

Elsewhere, ‘Wayward Child’, ‘Bad Penny’ and ‘Public Enemy No.1’ spring to mind as highlights, but there’s no ballast here, that’s for sure.

SOLO STAR

In the end, it was Rory Gallagher, the eponymous debut that the gang finally plumped for. Dave Fanning, Muireann Bradley and her father John were among its advocates. You might think this was in line with the ancient indie rule: “I prefer the early stuff.” But this is different.

For a start, it was the moment that Rory Gallagher – already successful with Taste, but not getting his just rewards – assumed the mantle of solo star and upfront leader. It was, on his part, a statement of confidence and responsibility. But there was more to it than that too. Rory kept his counsel, but the bottom line is that there were management issues, money issues, loyalty issues and more involved in the demise of Taste – and a feeling that the only way to deal with them was to light out on his own.

And so, Rory Gallagher, the album, comes across as a defiant record and winds up as a powerful predictor of his ultimate greatness.

Looking back now, you can see how the game had been going for Rory, and feel some of the anger that was boiling inside him. “What do you think of that,” the album opens, “I’m sleeping down at the laundromat.” It was the place he and his brother Dónal gravitated to, below the freezing flat that was Rory’s home at the time in Earl’s Court, London. It was deathly cold – because someone else was holding the money. There is wit and humour here – “Oh, come around and meet my friends,” he offers the listener, tongue firmly in his cheek – but also an alley cat’s feral moan in a song that ranks as a classic Rory outsider tale of the kind revisited in ‘Country Mile’.

‘For The Last Time’ more specifically captures the bile that surrounded the end of the Taste dream. “You’ve done me wrong / For the last time,” he charges, “You’ve sung your song / Now I’m going to sing mine / Out loud, so loud / Like the roaring sea.” It is a potent promise, on which Rory would follow through with a mixture of stoical determination and sheer bravado, working up and down the UK, and across the world, touring like he just couldn’t afford to stop.

Being on the move constantly, away from his base and from any idea of stability was tough – but it’s the life that was required of many musicians in that era. Rory just went further, worked harder. He pushed himself to the limit, and then, at times, even further again. ‘Wave Myself Goodbye’ leaves no room for doubt about how down the man could get, at least on occasion, though there is a touch of sardonic humour involved.

“I feel so blue,” he confesses, “I think I’ll wave myself goodbye.”

That vulnerability is captured in ‘Hands Up’. Everything, you sense, could capsize at any moment – or certainly that’s how it feels when you’re the captain of a ship that has to battle constantly against a roiling sea and waves that crash in gargantuan counter-splashes onto the deck.

“My world is upside down,” he laments, “My inside is inside out / I’m hanging to a leaf that’s shaking / that’s hanging to a branch that’s breaking off now.”

Sometimes you sense that the unrequited love is just anther way of expressing the deep, existential pain and dread of living. Despair and depression are there, a black dog barking but to what avail? “Clock on the wall,” he says, in a line that anticipates Shane MacGowan in ‘A Pair of Brown Eyes’, when the lead Pogue gives the walls a talking, “Why do you bother to chime at all?” Watching what’s going on in the world today, there is no doubting the timeless relevance of the enquiry. The clock doesn’t answer.

EXORCISING THE DEMONS

Underneath despair, inevitably, there is paranoia.

“And in the night I’m talking in my sleep,” he continues, “The things I say, I just can’t repeat / Don’t need no fingerprints to know / You’ve got your hands on my very soul.” Again, it sounds like he’s addressing those who had taken him hostage during the Taste adventure, rather than any love object with dark intentions.

I shouldn’t spoil the Podcast. There’s eating and drinking in this landmark record – acoustic and electric tunes, pounding bass and drums, piano here and sax there, and much more besides – on which Daniel Gallagher, Muireann Bradley and Paul Nolan cast fascinating new light. But what it brings us back to – one more time with a deep gut feeling – is the extraordinary virtuosity, the lyrical flair and the often underestimated cultural influence of the towering Cork (by way of Ballyshannon) music legend.

With Van Morrison from Belfast on one side and Philip Lynott from Dublin on the other, Rory Gallagher blazed a trail out of Ireland, showing us all that it could be done – that born into what was in so many ways a moribund, hopelessly conservative and often grim society at the time here, you could find the language to express the inner turmoil and the angst – the blues – and do it in a way with which people all over the world would fall deeply in love.

But also that, when it came to doing it live, to being on stage, to exorcising the demons, the place would be filled with an overpowering, inspirational, cathartic joy and togetherness.

Rory Gallagher made us all more fully ourselves. Without him, and the life he lived and the music he made, we would be in a different place now. And I can assure you it is much better here, where we are, in June 2025. Thirty years on, we are still greatly in your debt. Thank you Rory. Much love.

Niall

RELATED

RELATED

- Music

- 09 Oct 25

Album Review: Mary Stokes Band, Hometown Blues

- Music

- 26 Sep 25

Album Review: Robert Plant with Suzi Dian, Saving Grace

- Music

- 05 Aug 25