- Opinion

- 24 Oct 25

Bob Dylan's Through The Open Window: "The ancient footsteps that never fade"

Anne Margaret Daniel takes us on a deep-dive into Bob Dylan's Bootleg Series Volume 18: Through The Open Window, 1956-1963 – finding that "Dylan never lays anything down but brings it along with him, the past present and vital in his ongoing creativity..."

Once upon a time there was a boy named Bob Zimmerman in Hibbing, Minnesota, who put together a band with some of his high school friends. They’d practice in the garage of his home – bless Beatty Zimmerman for moving the car out and parking it on the street so they could rehearse – and the kids would call him “Elvis” and “Little Richard.”

The boy was just fifteen in December of 1956, when he and two of his pals from summer camp, Larry Kegan and Howard Rutman, down in the Twin Cities for the holidays, went to the Terlinde Music Shop in Saint Paul on Christmas Eve, and cut an acetate of some verses from songs they liked. They called themselves The Jokers, and Zimmerman played the piano and sang lead, while the other two boys harmonised.

They might have been fans of groups like Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, and Louis Lymon and the Teenchords, but the acetate is full of blues, rags and hollers. And rock and roll. Elvis Presley had a hit with 'Ready Teddy' and performed it on the Ed Sullivan Show in October of that year; the boys put it on their record. They also covered 'Boppin’ the Blues', 'Lawdy, Miss Clawdy', and 'Let The Good Times Roll', along with some slower soon-to-be-classics like The Five Satins’ 'In The Still of the Night' and 'Earth Angel'.

This is the earliest known recording made by the young man who would four years later be getting known as Bob Dylan. It is where seven decades, so far, of a career as a professional musician and live performer began – and it is where the titanic new box set, Bob Dylan’s Bootleg Series Volume 18: Through The Open Window, 1956-1963 begins.

Seven years: how is it possible that from fifteen to twenty-two this boy and young man could do so much, go so far, and make such a difference to his own times and to what’s come since? Hard work, luck, good friends, and yes, genius – but the beginnings of Bob Dylan are so multitudinous that The Fates, too, must have had more than a hand. Things like this, people like this, don’t come along every day or year or century. The story that the 139 songs, and song introductions, on the eight cds of this set tells is both a biography and the fullest imaginable portrait of the artist as a young man.

Steve Berkowitz, Grammy-winning co-producer of many releases in Dylan’s Bootleg series to date, and founder of Columbia’s Legacy division, and Sean Wilentz, historian and the author of Bob Dylan In America (2010), produced Through The Open Window. They’ve selected generously from the cornucopia of available Dylan recordings from these years, and included informal recordings made at Dylan’s home and friends’ parties, at the clubs and cafes of Greenwich Village; studio outtakes from Dylan’s first three albums; entire evenings from Gerde’s Folk City and – gloriously – the entire Carnegie Hall concert of October 26, 1963, complete with Dylan’s introductions to the songs.

Some tracks have been released before, and some have long been in circulation in varying degrees of audibility. Dylan fans will know some of the 'informal recordings' here from the McKenzie Tape or Minnesota Party Tape or of course Great White Wonder (which began bootlegs); all of them show the young performance artist hard at work. “What you hear is him honing his craft, perfecting his craft,” says Wilentz, singling out 'House of the Rising Sun' from 1963 – with an arrangement Dylan harvested from Dave Van Ronk – as a particularly fine example.

The brash young voice starts out with the sassy 'Let The Good Times Roll', and you can visualise Dylan’s fingers flat on the piano as he accompanies himself. This is the only song included from that 1956 acetate; only one song from Hibbing, and none from the one tape known to survive that John Bucklen made at Dylan’s house in 1958, is here.

Only select tracks are chosen from all the Minnesota recordings made from 1960 to 1963 by Dylan’s friends, including Bonnie Beecher and Tony Glover. Though I am very glad to hear Glover and his untouchable harmonica playing on 'West Memphis' from 1963, as he accompanies his lifelong friend while Dylan sings the blues, and Danny Kalb’s contribution on 'Hard Travelin’' and 'KC Moan', I’d have loved more Midwest. Why? Because what is here is so beautiful now; Berkowitz and Steve Addabbo have performed magic on the snappy, popping tapes of tapes. Disc 2 concludes with a selection of eight songs from Beecher’s tape that is stunning, especially 'Stealin’' and 'Dink’s Song'. It made me yearn for all of the 25 tracks from that May day in Minneapolis.

This said, Dylan’s life from 1961 for the next decade was centered in and near New York City. It’s right to hurry on to Greenwich Village, just as he did. Nothing else would be true to the story, and these songs tell a story as you listen to them – not just the stories within the ballads and blues themselves, but the tale of a troubadour moving so swiftly from singing other people’s songs to making his own voice.

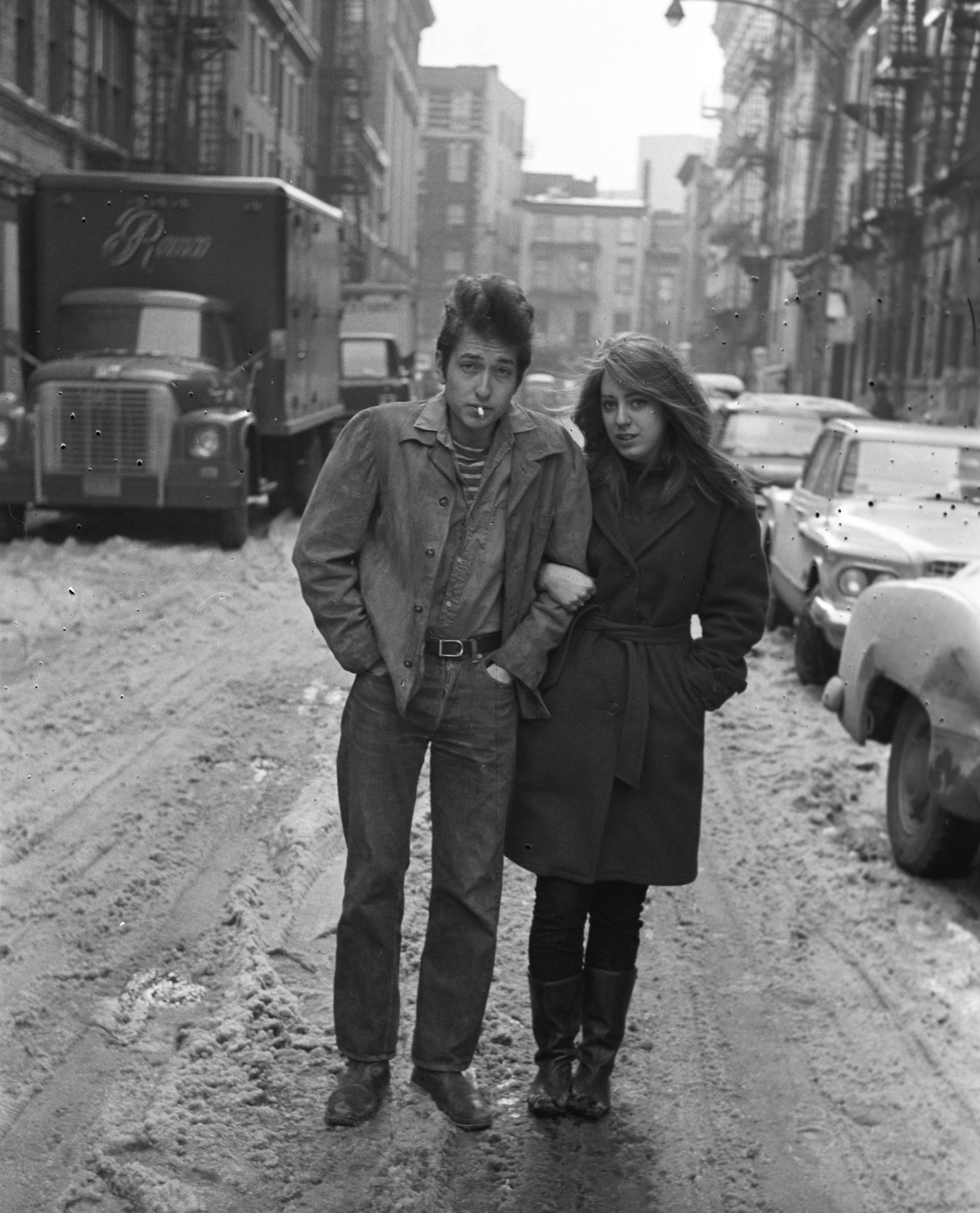

© Don Hunstein/Sony Music Entertainment

At first, he’s striving to be the best folksinger he can be – exaggeratedly so. In 'East Virginia Blues', recorded in Madison, Wisconsin just before he headed to New York, Dylan sounds like he’s become a member of the Carter Family, holding onto the lines and drawing them out about twice as long as do any of the Carters. Woody Guthrie’s influence on the young Dylan has been copiously and rightly acknowledged, by Dylan himself as he sings Guthrie’s songs at The Gaslight, in East Orange, Carnegie Chapter Hall and Town Hall.

His first performance of 'Song To Woody' at the Gaslight is intimate, comfortable: “Hey hey, Woody,” he sings, no adding the Guthrie. At Gerde's Folk City with Jim Kweskin a few months later, he performs 'Pretty Boy Floyd' in a near imitation of Guthrie’s own voice. While moving on at lightning speed to his own material, Dylan still drops Guthrie’s songs into his sets. Even in 1963, back in Minnesota for a visit, he wants to let his friends there know what he’s learned directly from the master: “Everybody sings a song called this land is your land….Woody Guthrie sang to me these verses here which nobody ever sings…these are the last verses he wrote to it.”

And then he sings:

As I went walkin’ that ribbon of highway

I saw a sign sayin’ private property

But on the other side it didn’t say nothing

This land was made for you and me

Sunday morning by the steeple

By the relief office I saw the people

They was starvin’, and I was wonderin’

Is this land made for you and me?

Glaringly absent from Dylan’s early Village days is 'Black Cross', the song he learned from another mentor, Lord Buckley, though you can find his beautiful and passionate version of the sad and cruel story of Hezekiah Jones online.

The young man who was swiftly becoming a coffeehouse sensation learned perhaps as much from Buckley, and Lenny Bruce and Hugh Romney (later Wavy Gravy) as he did from Guthrie and Van Ronk. Not just songs, but performance, delivery, onstage rap and banter and patter, and how to be a stand-up comic: all these things collaborate to make Dylan popular.

His sense of humor and comic timing pour out of the song intros, interject themselves into his phrasing and delivery of lines in, say, 'Talkin Bear Mountain Picnic Disaster Blues'. It’s a joy, though the incident it’s based on is not. “Fun for all, yippee” will never not make me laugh. His rhymes tickle him, too, and you can hear him snickering as he sings and the audience laughs: ticket and picnic; I’m skeered / a bears; casket / picnic basket. He truly loves a goofy rhyme – and an ad lib: “Cursin’ picnics.”

The rarity of Dylan’s performance of some of the songs on Through the Open Window is easy to forget when you’re familiar with them. You might know a song well from, say, the Witmark Demos. But remember that Dylan might have only performed it two or three times, ever, and that was back in 1961 or 1962.

Wilentz laughs, “I mean, how many times have you heard him do ‘Deep Ellum Blues’?”

The answer is that Dylan’s only played it two times, both in 1962 (though he might have done some chords in sound checks decades later). The version included here, from Gerde's, is part of the almost indescribably fine set he played there on April 16, 1962.

The whole five-song set is here, along with Dylan’s introduction to the last song, a new one of which he only has partially completed. Wilentz is right to call this version of 'Corinna, Corinna' “revelatory.” It’s a work still in progress, and Dylan begins it deceptively goofily, laughing with someone in the audience and saying that they’re “gettin’ sneaky there” even as he’s playing his intro. Then the words and the passionate waterfall of the guitar hit you at once. The place falls silent.

Corinna Corinna, gal what’s on your mind

Corinna Corinna, gal what’s on your mind

I been sitting drinkin’ about you baby

Jus’ can’t keep from cryin’

Ain’t got Corinna I can’t be satisfied

Ain’t got Corinna I can’t be satisfied

I got ta git along my trail

Got a hellhound by my side

I got a bird that whistles I got a bird that sings

I got a bird that whistles I got a bird that sings

But I ain’t got Corinna

Life don’t mean a thing

You got a .32 special built on a cross of wood

You got a .32 special built on a cross of wood

I got a .38/20, gal, that’s twice as good.

Corinna Corinna baby please come home

Corinna Corinna baby please come home

I been worryin about you baby

You been gone too long.

No time to catch your breath: he’s on to 'Deep Ellum' in a speedy version, with a high-pitched jingle-jangle harmonica, and whoops and yips as he sings. Then he ends with the verse he’s written so far of a new song he pronounces “blown” when he sings the title line of 'Blowin’ In the Wind'.

The box set could end right here, the Gerdes set sounds so perfect and matchless – but it does not. Wait, there’s more. The young Dylan is the Ginsu knife commercial but with genius. Wait, there’s more. Sharper and better and keener than what you just heard; and the next track more so than what came before. It’s happening at the speed of light, too.

The songs Dylan sings about women, and, significantly, from a woman’s point of view are vitally important in his early career. He introduces 'Young But Daily Growing' at Carnegie Chapter Hall in 1961 thus:

“There’s this Irishman, Liam Clancy, sings this one. This is a straight copy, straight imitation. (He laughs) I’m not gonna imitate the voice so much, I can’t get that accent down quite good enough. It’s an Irish one, though, an’ a very sad song. Maybe this is the ‘Merican version of the Irish version of Liam Clancy’s version. I heard Liam sing this in the White Horse Bar, an Irish bar.”

He’s not kidding that it’s straight imitation, and Dylan’s voice reaches for that lovely tenor of Clancy’s, tentatively at first but then settling in well. The song is sung from the point of view of a woman in her twenties, married to a young lord who is a boy of fourteen, still in school, and “the fairest of them all” on the football field. He dies just two years later, leaving her to raise their son.

I’ll buy my love a shroud

Of ornamental brown

And place it on his grave

while the tears come trickling down

O it’s once I had a true love

But now I have none

But I’ll watch his bonny son

While he’s a growin’…

Similarly, 'Dink’s Song', a woman’s lament after she’s abandoned by her lover once she is pregnant, is one of Dylan’s best performances on the whole record. 'North Country Blues' is another. And as a corollary, if that’s the word, he drops a notable verse into 'Talkin’ New York' that gets a big laugh from the coffeehouse crowd:

Well I got on the subway and took a sheet

Got off on 42nd Street

I met this fella named Dolores there

He started rubbin’ his hands through my hair….

'Liverpool Gal' is released at last, sounding lovely, all five minutes and 47 seconds of it. July 17, 1963, at a party in Minnesota, is the only time Dylan’s performed it. He wrote the song on his first trip to England, in December 1962-January 1963.

“His love songs up until now are mostly about long-term relationships gone bad. This is a one-night stand where the girl’s in charge,” says Wilentz. The young man arrives in London Town for the first time, and meets a girl. They walk by the Thames and end up at her house, where they talk for hours by the fire in “sweet conversation.”

…The night passed on with a drizzling rain it’s one thing I’s finding out

A walkin’ and a ramblin’ I knew too hard, of her love I knew nothin about

When I awoke next mornin the rain had turned to snow

I looked outside her window and I knew that I must go

I didn’t know how to tell her, I didn’t even know if I could

I smiled (he laughs, and begins the line again) She smiled a smile I’d never seen and said she understood…

So it’s now I’m leavin’ London Town but the town I can soon forget

Likewise its windy weather, likewise some people I’ve met

But it’s one thing that’s for certain as sure as the sun shines down

I’ll never forget that Liverpool girl who lived in London town.

“That’s one of the best songs I’ve ever heard,” says one of the party guests at the end.

When Dylan arrived in London that freezing December, he was met at the airport by Philip Saville, who had convinced Albert Grossman to send Dylan to London to be in the BBC play Madhouse on Castle Street (he escaped this, and all that remains of that fiasco is 'The Ballad of the Gliding Swan', included on this record, a wild bloody little shard that should be on Paul Clayton’s 'Bloody Ballads' or 'Unholy Matrimony').

Saville’s lover, the painter Pauline Boty, met Dylan at the airport too. They swept Dylan straight to a Royal College of Art party on Blenheim Crescent, where one guest recalled that he played music for them all night. Dylan moved from flat to flat as a houseguest for much of his time in London, eschewing hotels like The May Fair because he played his guitar too late into the night to suit the paying folks on his hall.

John Hughes of the University of Gloucestershire has done fine work on Boty and her influence on Dylan as well as on the English pop art scene. There’s no one on one correspondence between Boty and the girl in this song – she wasn’t from Liverpool, and there’s no evidence that she and Dylan had an affair – but surely her artistic talent, great beauty, and much mentioned kindness lie behind this song in pleasant ways.

The snippets of conversation with folksingers, of Dylan chatting to other party guests and audiences, are full of whoppers about being from Gallup, New Mexico, and being in carnivals for six years and the like. He’s so appealing you don’t mind the bullshit, and you grin even as you listen to it. He’s breaking away, making things up and fictionalising his own life even as he’s starting to write his own autobiographical or reflective songs.

Introducing 'Long Time Gone', he says, “Nobody’s ever heard this one, it’s the first time I’ve sung it.” He’s performed it, according to his website, only twice.

I remember when I’s ramblin’

Along with the carnival train

Different people, different towns

They all looked all the same

I remember children’s faces best

I remember ramblin’ on

I’m a long time a-comin’

I’ll be a long time gone

At the end, Dylan asks, “You like that song?” Mm hm, murmurs someone in the background. “I sorta made up half the words to it right there, y’know…. I wrote that for myself, I figured I’d been writing too many songs for other people (he chuckles) ‘You ain’t written no songs about you.’ Y’know, an’ I says I gotta do something about that, you gotta get somebody to write a song about you I write songs, I can write a song about me just as good as anybody else can.”

Even as he’s writing these songs for himself, songs of myself, he’s keeping what he’s learned already, too. 'Roll On John' reminds you of this. Those long, drawn-out words and held notes he cherishes; they’re full of nostalgia and longing but not loss. Dylan never loses anything. He never lays anything down. Dylan doesn’t move from old Bob to a new Bob, changing his style and way and themes and songs. He carries everything that’s past with him.

Bob is the living embodiment of not only Walt Whitman’s “I contain multitudes,” but William Faulkner’s “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Nothing’s past with him. Roman emperors and Aramaic shepherds and 1960s hippies walk in the same sandals, the ancient footsteps that never fade. We hear all that starting on Through the Open Window.

We hear it, too, in his collaborations with other musicians. His early career as a harmonica player is showcased here. When Dylan arrives to play harmonica for Harry Belafonte on 'Midnight Special', someone tells him to take off his boots. He agrees. IMAGINE ANYONE TELLING HIM TO TAKE OFF HIS BOOTS TODAY.

Start off with something exciting, he’s instructed. And he does. 'Wichita' is beautiful, and 'Dangerous', what a murder plaint! Bob’s howling harmonica loves rising and falling with Victoria Spivey’s voice, rich as poundcake and dark and ominous as an arriving storm. I’ve already mentioned the two songs he plays with Danny Kalb, and 'West Memphis' with Tony Glover.

And then there is his best-known, most popular collaboration – and most formative in his career – of the early years: that with Joan Baez. Introducing him at Forest Hills in 1963, she calls “Bobby Dylan” a “phenomenal young man, who’s been writing beautiful songs, beautiful poems, beautiful stories.” When during the March on Washington she comes up to harmonise with him on 'When The Ship Comes In' you hear all that beauty she’s mentioned, enhanced by her own mermaid’s voice.

Discs 7 and 8 are Dylan’s entire Carnegie Hall concert of October 26, 1963. Please listen to it all the way through. It’s the closest you’ll ever get to being a fly on the wall, a face in the crowd, to the pinnacle of the start of Dylan’s career. The song selection and his set list is as well organised as, better than, the chapters of any book.

Dylan’s conversation with the audience matters too: his mockery of an academic taking apart 'Blowin’ In the Wind' because he doesn’t understand it, a funny riff on hootenannies, the shout-out to Paul Clayton, the intros to 'The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll' and 'When The Ship Comes In', and most of all to 'Masters of War':

“Some people say this one, this song I wrote is very naïve. Well, I got to stand here and really not care because I do actually hope that the masters of war die tomorrow.”

The Carnegie Hall concert is, as Wilentz puts it in his superb and book-length liner notes, “the end of the beginning of Dylan’s long career.” Beautifully said. Yet as I think of all that came hereafter, and the fact that Dylan never lays anything down but brings it along with him, the past present and vital in his ongoing creativity, I recall T. S. Eliot’s line instead: “in my end is my beginning.”

All lyrics by Bob Dylan © Universal Music Publishing Group

All previously unpublished lyrics by Bob Dylan © Babinda Music 2025

Bob Dylan’s Bootleg Series Volume 18: Through The Open Window, 1956-1963 will be released on October 31.

RELATED

RELATED

- Opinion

- 17 Oct 25

2025 International Famine Commemoration to be held in Chicago

- Opinion

- 16 Oct 25