- Music

- 20 Nov 25

Miami Showband Massacre survivor Stephen Travers: "The voice of the victim is perhaps the most effective antidote to radicalisation"

Stephen Travers discusses his powerful new book The Bass Player, which reflects on his life before and after the Miami Showband killings.

In Stephen Travers’ The Bass Player – nominated for Biography of the Year at the Irish Book Awards – the musician compellingly reflects on his life before and after the Miami Showband Massacre. Building a successful career as a musician in the group, everything forever changed for Travers 50 years ago, on July 31, 1975, when he and his bandmates were stopped at Buskhill, Co. Down, at what appeared to be a British military checkpoint.

They were ambushed by loyalist paramilitaries, and three members of the group – Fran O’Toole, Tony Geraghty and Brian McCoy – were murdered. In the book, Travers describes the ordeal in harrowing detail. Two serving Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) soldiers, and one former UDR soldier, were found guilty of the murders and received life sentences, before being released in 1998 as part of the Good Friday Agreement.

There remain serious questions over suspected British state collusion with loyalist terrorists, with the 2011 Historical Enquiries Team (HET) report on the Miami killings raising “disturbing questions about collusive and corrupt behaviour”.

Elsewhere in The Bass Player, Travers also recounts his subsequent life trajectory, which saw him become founding director and editor of The Irish World. In addition, he has addressed victim support and radicalisation awareness conferences across Europe and the US.

In a notable moment in the book, he recalls how a 30th anniversary concert for the band in Vicar Street, in 2005, initially had poor sales, before he hit the promo circuit and turned into it a sellout. However, he acknowledges that he was initially hesitant to speak to the media, and describes it as a moment where, perhaps for the first time, he publicly started discussing his traumatic experiences.

“That was the 30th anniversary of the incident, and up until then, I had been in denial,” says the Tipperary native. “I didn’t want to know about what I would have considered conspiracy theories at the time, about collusion and all that type of thing. But around that time, I was asked to engage in the Barron tribunal, which was looking into collusion. The evidence that I saw, I wasn’t able to deny it anymore.

“That was a turning point for me and I began to look into things. But it took me 30 years to say, ‘I better sort this out’, because being in denial means suppressing a lot of memories and things I should have seen clearly.”

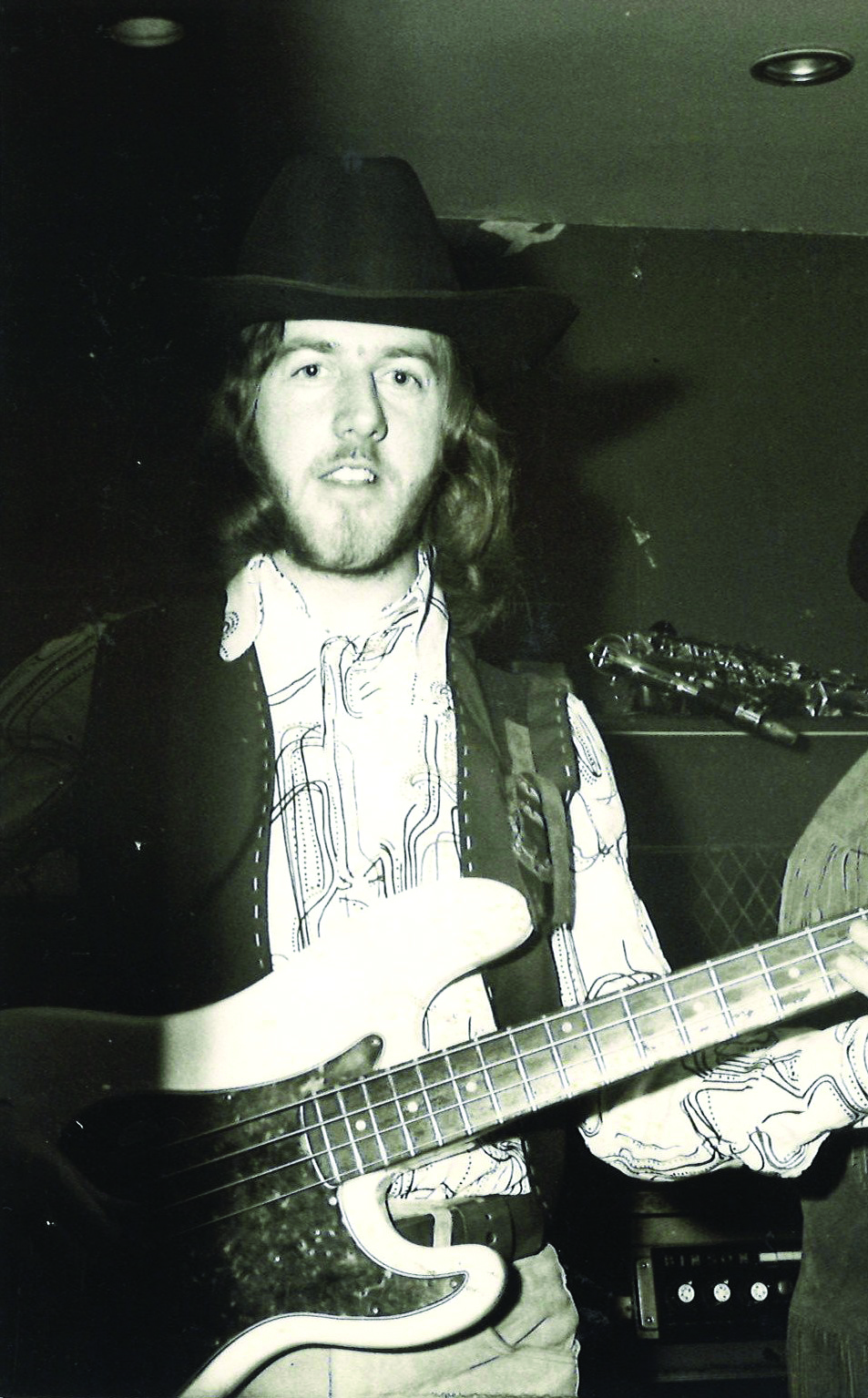

Stephen Travers and Johnny Fean

Stephen Travers and Johnny FeanIn another extraordinary moment in the book, the author recounts travelling to a 2013 event at the Warrington Peace Centre, 20 years after the IRA bombings in 1993. Travers broke down in tears as he began to discuss his experiences, the first time it had happened publicly, almost 40 years after the Miami killings. It’s a moment that shows the devastating long-term effects of trauma.

“That was Warrington, where the two little children were murdered, Johnathan Ball and Tim Parry,” says Travers. “There is a self-preservation mechanism for victims – most of us don’t allow ourselves to get too close to it. It’s almost like standing at the edge of a cliff; you get too close to what happened and it can affect you.

“So I was careful not to let it get to me. But when I walked in there and saw the pictures on the wall, it’s just two children, and I thought to myself, ‘That’s completely wrong.’ That’s when it all wrong for me that evening. I think the name of the chapter is ‘When The Wall Fell’.”

Elsewhere in The Bass Player, Stephen writes about occasionally visiting the field where the Miami killings took place, and reflecting on how his life was permanently changed. It makes for a haunting rumination on the dark, traumatic moments that arrive in life, sometimes out of nowhere – and how we deal with them.

“I’m glad you asked that, because part of the purpose of this book is to challenge the reader,” he says. “I’m telling you I’m dealing with it, and you’ll notice the name of the book is The Bass Player, but the subtitle is Surviving – which is the present tense. So what I’m telling the reader is, ‘Look, this is how I’m dealing with it.’ But the challenge to the reader is, ‘How would you deal with it?’”

It seems as if we make a collective deal that along with the joy and transcendent moments in life, there will sometimes be incredible darkness – and we have to deal with it together, as best we can.

“What you just said there is interesting,” says Stephen. “‘We have to deal with it.’ Hopefully, if we look at history and listen to the voice of the victims – and this is not just about me – you won’t have to deal with it. I became involved with Tarp, the Truth and Reconciliation Platform, which supplied a platform for people to talk.

“Ours is a fairly high profile case, but there are horrendous stories out there that are never heard. We did it online and at live events. It’s clear that the voice of the victim is perhaps the most effective antidote to radicalisation – the most effective deterrent to violence as a means to change society. That’s what’s important here. The book doesn’t lecture people, it’s there to challenge people and say, ‘Is there a better way?’ I think there is.”

Another deeply affecting episode in the book comes with Travers’ meeting with Derry man Richard Moore, who was permanently blinded in 1970, after being shot with a rubber bullet by a British soldier. Moore subsequently founded the organisation Children In Crossfire, and in 2008, he invited Travers to go and see their work in Tanzania.In Dar es Salaam, Travers saw how, despite limited resources, a young Irish doctor was delivering cancer care to children, in what was then the only hospital in East Africa providing chemotherapy free of charge.

Stephen Travers in 1970

Stephen Travers in 1970“Her name is Trish Scanlan and she’s from Wicklow,” he says. “That’s a lady who could have had a glittering career, a fabulous doctor. She chose to help the children in the Ocean Road cancer care centre. It is powerful, because it shows what we can do. We come from a little island and we can effect change. Every life saved has the potential to change the world.

“When you consider, going back to the very start of that chapter, that Richard Moore was shot in the face with the rubber bullet. He came from a poor area, part of the Creggan, and his father was an unemployed shoemaker. And here’s a man that has been instrumental in opening hospitals – I had a whistle-stop tour and saw some of the most terrible things ever.

“These are inspirational people. I’ve met and worked with a lot of my musical heroes, but I found other heroes as well. You don’t have to look up to find a hero, just look around you. Your life becomes very satisfying when you meet some of these people, there’s a lot of excitement.”

Stephen Travers by Kieran Slyne.

Stephen Travers by Kieran Slyne.More recently, in December 2021, Travers and other victims of the Miami killings agreed £1.5 million in damages over suspected state collusion with loyalist terrorists. At the time, he said he agreed to settle over the UK government’s plans to introduce the controversial Legacy Act, relating to killings by police and soldiers during the Troubles.

“That rushed us into accepting a settlement,” says Travers. “It’s shocking, it was passed by Boris Johnson and his acolytes. They claim it was because vexatious claims were being made against the security forces. That’s simply not true, and when I had a meeting last year with the current Secretary of State, Hilary Benn, he was trying to sell this idea of, ‘Well, we have to stop these vexatious claims’.

“They talk about a witch-hunt against the security forces, and that simply isn’t true. So I said, ‘Look, forget Northern Ireland. Tell me is there a witch-hunt against the security forces in Birmingham?’ He said, ‘Of course not.’ And I said, ‘Well, in that case, why does your Legacy Act shut down access for the loved ones of the victims of the Birmingham pub bombings? How can you possibly say that the reason for the legacy act is a witch-hunt against the security forces?’”

He reflects further on the situation.

“And then they have this thing called the ICRIR, which is information retrieval,” Travers continues. “They try to say, ‘Well, you don’t have to go to court’, because they don’t want you to go to court. They spent £1.5 million on a settlement for us, and about the same for 10 years of legal fees. £3 million is a lot of money to throw at something just to shut it down.

“And when I refused the settlement, they said, ‘Well, we will have the Legacy Act over the line by Christmas. And when that happens, your case will be shut down as well.’ As it turned out, they didn’t get it over the line, but they also told me I would be the cause of the other litigants not getting closure.

“It was blackmail, and all sorts of coercion and bullying. So I eventually said I’d settle, but who knows – maybe this isn’t over yet.”

• The Bass Player: Surviving The Miami Showband Massacre is out now.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 06 Jan 26

Imelda May pays tribute to late Donegal businessman Stephen McCahill

- Music

- 06 Jan 26

Aslan announce 3Olympia headline show

- Music

- 06 Jan 26

KNEECAP say new album is coming this year

- Music

- 06 Jan 26