- Lifestyle & Sports

- 24 Aug 25

Miguel Delaney on the FIFA Club World Cup & Sportswashing: "I do genuinely think this is the start of a real transformation in football, and one that’s been coming for a long time"

Leading sports journalist Miguel Delaney dissects the Club World Cup to show how football has been taken over by capitalism and Gulf states, as well as the motivations that pushed him to write his essential guide to understanding the modern game, States Of Play.

The game’s gone.

It’s a phrase you’ll hear fans say in response to modern football. VAR? Rubbish. Holes in socks? Ridiculous. Expected goals? Woke nonsense.

This summer, the expanded 32-team Club World Cup in the USA had all the trimmings. There were half-time interviews, half-time shows, and players coming out of the tunnel with their names announced WWE-style.

Behind the pageantry, more troubling truths emerged: the financial greed and political influence from those who don’t have the best interest of the sport, and often people, at heart.

Sportswashing – the practice of using sport to improve the public image of an entity, such as a country or organisation – was rife.

There are few better qualified to discuss this than Spanish-Irish journalist Miguel Delaney. The Chief football writer at The Independent in the UK, his book States Of Play is a definitive account of how capitalism has devoured the sport, and was named Football Book of the Year 2025.

“There’s been a big debate over whether it worked as a tournament,” Delaney says of the CWC. “I don’t think that matters. What’s important is that it worked for Gianni Infantino’s (Fifa President) purposes. He was able to show to the big clubs that he could deliver this new tournament.

“There are several caveats to that. He needed the significant indirect backing of Saudi state money. DAZN paid $1bn for the TV rights. This was around the same time that the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) took a 10% stake in them.

“Clubs have been trying to unlock that PIF money for years. So Infantino suddenly got all the big clubs on his side. It’s a shift that’s probably been underappreciated, because for decades big clubs thought Fifa was a nuisance, whereas now it’s a player.”

Miguel Delaney.

Miguel Delaney.Each Gulf state has its own socio-political reality, but share troubling common ground when it comes to human rights. Most will remember the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, and the allegations of widespread abuses involving migrant workers. There were reports of poor conditions, withheld wages, and unexplained deaths among those building stadiums. Saudi Arabia and the UAE, meanwhile, rank poorly for press freedom.

In May, a group of lawyers alleged that Fifa wasn’t following its own human rights rules by having the 2034 World Cup in Saudi Arabia. Just a month ago, The Guardian reported almost 600 people had been executed over the past decade in the Kingdom for drug-related offences, often by decapitation.

Then there’s the debates over women’s or queer rights across the Gulf. It’s easy to see why these states seek image improvement through football.

“The tournament couldn’t have been held without the Saudi sportswashing project,” says Delaney. “They obviously have some sort of relationship with Infantino. It’s been well documented. Saudi money indirectly made the tournament happen. That links to the [Saudis’] wider project, this long road up to the 2034 World Cup, which is classic sportswashing really, because it’s tournament hosting.”

One of the participating teams, Riyadh-based Al Hilal, have signed global stars such as Neymar (who left after playing just seven games) as part of a wider plan to raise Saudi football’s profile.

“One of the more cynical interpretations of the Club World Cup is that it’s a Trojan horse,” Delaney explains. “I think it is crucial, in terms of sportswashing, that Saudi Pro League clubs have an equivalent competition to the Champions League. We know Abu Dhabi, or Manchester City’s owners, were really interested in this competition. Same with Qatar, who own PSG.

“It’s about using a global tournament for international projection. That’s what a lot of club ownership is about.”

Money from states, billionaires, and private equity affects what happens on the pitch by distorting football’s economics. Wage inflation has widened the gap between European giants and everyone else.

The Club World Cup claimed to address this. The prize money said otherwise.

“Chelsea got $114 million for winning it, whereas Boca Juniors got $14 million,” Delaney notes. “So I’m not sure how that exactly addresses the inequality in the game. There wasn’t that much memorable football. The stadium attendances were mixed. But none of that really matters.

“I think this is a landmark moment in football history, because of what Infantino has been able to put on, and how it’s changed the attitude of the big clubs. I do genuinely think this is the start of a real transformation in football, and one that’s been coming for a long time.

“It’s something that specifically comes from the United States’ economic model. States buy clubs for political capital. Funds and billionaires buy them for good old financial capital. They see the future as a kind where you can make money by being in a more international market.”

The politics and the spectacle collided in surreal ways, summed up by Donald Trump’s presence. There was the awkward video of Juventus players at the White House as he disparaged the women’s game, and the bizarre image of the Chelsea squad lifting the trophy with the US President planted beside them.

“It felt like an escalation of the Bisht in Qatar 2022,” Delaney reflects, recalling the Emir of Qatar placing the ceremonial cloak on Lionel Messi. “The Bisht itself is an otherwise innocent garment that bestows honour. Suddenly, Qatar is at the centre of this moment of celebration of history. With Trump, it’s more direct. There he is in the middle of it, clearly not wanting to leave.

“The US is a liberal democracy. At the moment, a flawed liberal democracy. But I’m not sure it’s quite as centralised as you’d see in autocracies.”

2022 FIFA World Cup Qatar.Korea vs Uruguay November 24, 2022. Education City Stadium, Doha, Qatar. Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. Official Photographer: Heo Manjin.

2022 FIFA World Cup Qatar.Korea vs Uruguay November 24, 2022. Education City Stadium, Doha, Qatar. Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. Official Photographer: Heo Manjin.With the US hosting the next World Cup, could Trump use it for political advantage the same way other leaders have?

“A lot of human rights groups would say the American World Cup will be used to further his current political agenda, which is obviously authoritarian leaning. But you wonder how much control you have over Trump. Some of this has to be linked to his own idiosyncratic personality.

“With him, it’s much more about basic ego. There is an element of WWE to this. Which sounds basic and cartoonish, given the genuinely important and complex topics we’re talking about.

“But these are the sort of figures involved. The Gulf rivalry has driven a lot of modern sportswashing. Ultimately it does come down to petty rivalries between very powerful men as well.”

Of all those men, one looms large over football – Fifa President Infantino, who replaced Sepp Blatter after the 2015 FIFA corruption scandal. As Delaney puts it, he was a “reform candidate”.

“But there was no reform of the structure,” he notes, adding that in Fifa (and Uefa), the president has the power to operate like a head of state, bestowing the influence of football wherever he sees fit.

"Infantino sees himself in the sphere of world leaders. Trump isn’t the only one he’s got a relationship with. It was Vladimir Putin around 2018.

“There’s that infamous photo of Infantino sitting beside Putin and [Saudi Crown Prince and Prime Minister] Mohammed bin Salman. The Trump administration very much encouraged Infantino’s relationship with Mohammed bin Salman. It absolutely is a concern that these are the sort of world leaders that Infantino seems to have the closest proximity to.

“It’s not serving football. It’s not necessarily serving society either.”

(Left to Right) Mohammed Bin Salman, Gianni Infantino and Vladimir Putin in 2018.

(Left to Right) Mohammed Bin Salman, Gianni Infantino and Vladimir Putin in 2018.Was there a specific moment that pushed Delaney to write States Of Play?

“The job used to be 70 to 80% about games on the pitch. Now I’d say that’s about 25%,” he explains. “The news cycle is relentless. All the narratives around games. There’s transfers, which is a separate industry in itself. Then there’s geopolitics. It was around the draw in April before the Qatar World Cup. I remember the moment realising that there’s a book that could actually tie this together.”

You’d expect a degree of backlash, given the subject matter, as well as the powerful organisations and figures discussed throughout the book. Perhaps the source of the discontent is more surprising.

“I was covering Manchester City’s run to the treble in 2023,” Delaney says. “I found myself in airports, hotels or restaurants with City fans. Some are civil, but I got a lot of aggressive abuse. I’m not talking about the fanbase as a whole, just minority sections within it.

“There’s tribalism and psychological dynamics. Ultimately there is a cynical use of the psychological attachment that football brings by powerful entities behind the club. Some fans take it as their identities being criticised.

“I think it’s pro-City to not want them owned by an autocratic state. I would extend this to capitalist funds and billionaires. I don’t think they should be owning clubs either.

“There’s a spectrum, and states are at the extreme end of that spectrum for multiple reasons.”

As a fan himself, has confronting the ugly realities of modern football made it harder to enjoy the game?

“It influences your thinking,” Delaney notes. “It's hard not to see clubs in terms of who owns them. Especially with the influence owners have. It’s them who are voting at Premier League meetings. They've become intrinsic to the identity of clubs.”

Still, the job has its perks.

“I would say there’s nothing like going into a big game at international tournaments,” Delaney says.

“The club game has never been more financially conditioned. From years of research, we know there’s a 90% correlation between what clubs spend on wages and where they finish in the table. Manchester United at this point might make up a considerable part of the 10% aberration…

“But in the international game players are doing it for glory. You can't buy players. It has this pure element of coaches trying to figure out what to do with their team.

“One of my most treasured memories is Copacabana in Brazil in 2014. You've got fans from all the nations, and it’s a scene of great humanity. And then you go to the games, where the atmosphere surrounds this and amplifies it.”

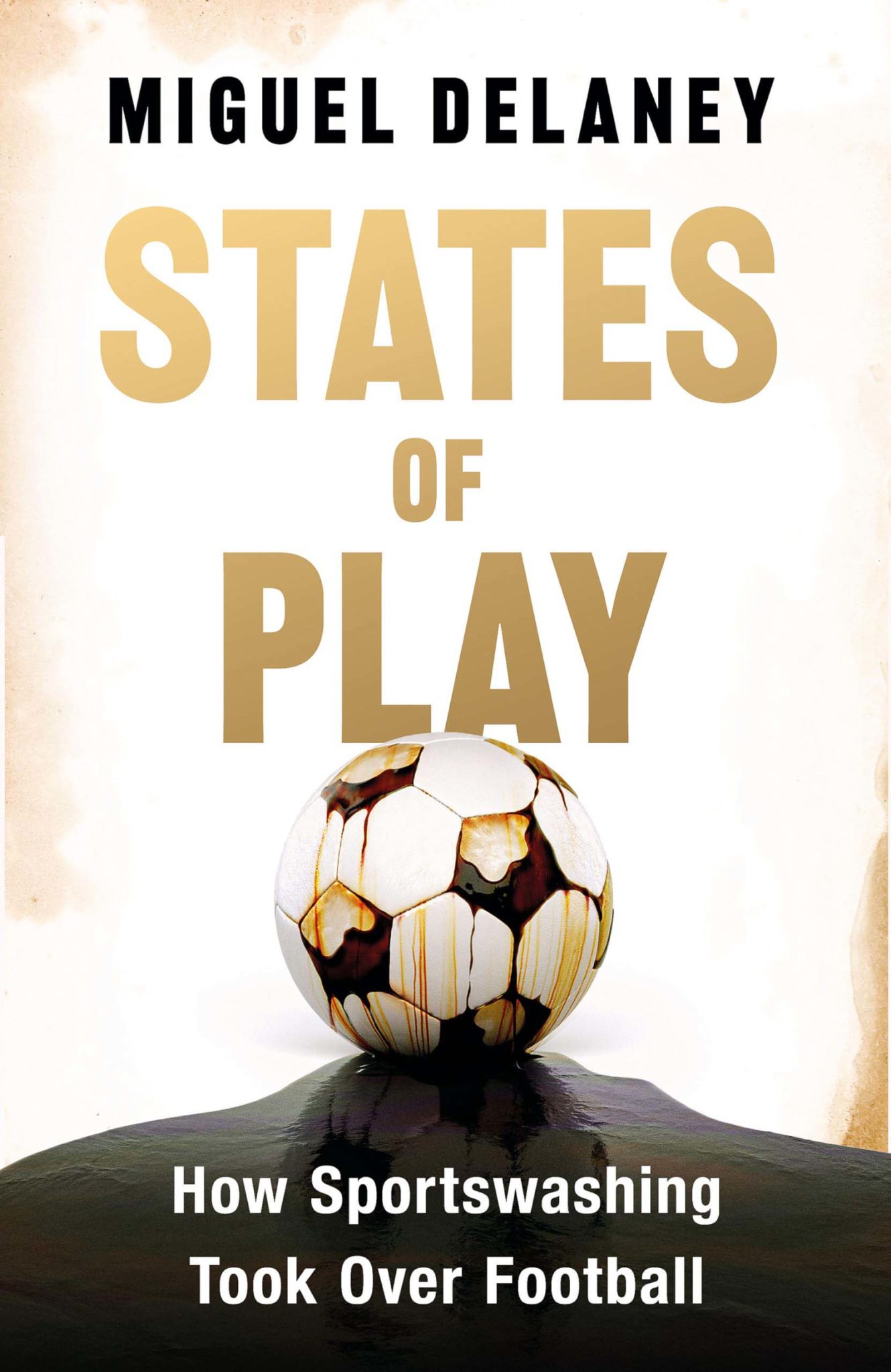

States of Play by Miguel Delaney.

States of Play by Miguel Delaney.In the final chapter of States Of Play, Delaney lays out some reforms he’d make to bring the game back to fans.

“One of the first steps I would take is recreating something with the same effect as the foreign player rule,” he says. “Before 1995, if your club was competing in Europe, you could only have three foreign players.

“You can recreate it from a different direction, which is essentially having three of your starting line-up, or more of your squad, having to be homegrown players. It becomes about training and its development. One of the effects of this is the super clubs don’t have as many available spaces in their squad for kind of talent they want to buy in.

“It means that players stay at clubs longer. This was why, before 1996, you could have Ajax keeping the team together and winning the Champions League. You could have Red Star Belgrade winning the Champions League.

“It starts to bring more parity in football, and if there’s more parity, it means a lot of these kind owners aren’t necessarily interested in clubs in the same way.”

• States Of Play is available now.

RELATED

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 11 Jan 24

Liam Brady: "Where I fell out with Jack was the way he kind of discarded me"

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 09 Jan 26

Second drop of KNEECAP x Bohemian FC jerseys to go on sale today

RELATED

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 19 Dec 25

Tullamore D.E.W. Distillery: Gift an experience that engages every sense

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 15 Dec 25

Bohemian FC and KNEECAP team up for new jersey fundraising for ACLAÍ Palestine

- Competitions

- 12 Dec 25

WIN: Lunch For Two From Forge Wood Fired Pizza

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 12 Dec 25

Minding Creative Minds to hold December meet and greet

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 10 Dec 25