- Lifestyle & Sports

- 03 Jun 25

Ib Jorgensen at 90: "It was good to see the Irish designers being so well received during the recent London Fashion Week"

“If I dropped dead tomorrow, I’d be lucky.” One of Ireland’s all-time most acclaimed fashion designers, Ib Jorgensen recently turned 90. Here, he talks about his life in fashion – including dressing Ireland’s first woman President, Mary Robinson, and the first women in the Irish Army Women’s Service Corps – his own favourite designers, his views on the industry now, and why he came out of retirement to open a design and fine art gallery in Dublin.

Ib Jorgensen reached the ripe old age of 90 just a few months ago.

Ib is a legend in Irish fashion. He was one of Ireland’s most successful and acclaimed couturiers – or luxury apparel designers if you want to be more literal! – from the 1950s to the early 1990s. During the ’90s, he elected to move on from the grind of creating new looks and collections every season, but he’s sill in business, operating a design gallery on Dublin’s South Anne Street.

What might seem extraordinary, given his age, is that Ib himself opens the shop in the morning – and puts in a five-day working week there.

So, what’s it like being 90, I ask?

“It’s no different to being 89!” Ib laughs. “Everybody thinks I’m very old now, but a year ago they didn’t. As soon as you’re 90, too bad – you’re gone! But I don’t feel any different.

“I had a huge birthday party planned,” he says, “but it was cancelled because of Storm Éowyn. I had booked the venue for 55 people, but the day before, they had to cancel it because they couldn’t take responsibility – and it was an issue because of difficulties delivering the food, and so on.

“Several people had speeches prepared,” he adds. “They said they could do it another time, and I appreciated that, but I decided that what was past was past. I’ll have a small dinner party instead, at some point. I’ve always like entertaining my friends. It’s part of my way of life, and it’s important to me.”

Ib’s decision to retire from the fashion industry in 1994, was provoked in part at least by the government of the day.

“The VAT rate went from 10% to 21%,” he recalls. “That was why I ultimately closed. It’s now 23%. It’s almost a quarter of your income.

But there were other complicating factors.

“You couldn’t get young people in to learn the trade,” he elaborates. “All the younger people were leaving the sector to earn quick money elsewhere. And you couldn’t blame them, because to train as a dress-maker took four years and you weren’t paid a lot of money.

“You were trained to come in with people like Sybil Connolly, Irene Gilbert and myself, who’d have maybe three or four people, so they learned every single thing and became good dress-makers. They were mainly women. If they got married and had children, they could extend their income by making clothes at home for people. It was an investment in their own time.”

Jorgensen himself was a graduate of the Grafton Academy of Fashion Design.

“When I finished, I used to teach there in the evenings and I also used to be an examiner of the clothes the students were making,” he recalls. “I always used to tell the students that any of my criticisms were constructive, intended to help them, and I might say something like, ‘I would have done this, and you might like to consider that the next time round’. It was, and is, amazing how much talent is going through the Grafton Academy. It has made an immense contribution to the industry here.”

FLAIR FOR FASHION

So much of what happens to us in life is an accident. Ib wanted to do architecture, but having come from Denmark as a teenager – when his family moved here – he didn’t have the requisite Irish in his Leaving Certificate that was required to ‘get in’ to the course. He ended up going to the Grafton Academy instead. Does he ever regret not having done architecture?

“No, I don’t regret it,” he says. “You can’t live on regret. But that Leaving Cert story is true. There were people in my family who could draw and paint, so that talent was in the blood, so to speak.”

That door closed, it dawned on him that he might have a flair for fashion.

“My mother was a very well-dressed, smart woman,” he explains, “but the design element came from my father’s side of the family. His eldest brother was an architect whose son was a very well-known painter in Denmark and whose younger sister was a painter for Danish Royal porcelain. So, there was always talent there. My father could draw, too. And I could always draw and paint – at boarding school, I won a couple of things. So it was in my genes.”

Are your genes really that important?

“I think so, yes. Your genes are part of your very being, whether you like it or not!”

Is his longevity part of that, too?

“Yes,” he laughs, “on my father’s side. They all died around 90 to 92, so I may have two years left! I don’t mind, I’m ready to go. I’ve no problem with it. If I drop dead tomorrow, I’d be lucky. And I mean that honestly.”

Is he religious?

“No.”

So, you’re reconciled with the fact that it’s all over when you die?

“Yes, I have. That would be the end of the journey.”

You look remarkably well, and younger than your 90 years – how do you look after yourself?

“I played a lot of tennis several times a week and I used to do a lot of long walks. And I loved dancing!” he smiles. “I never had a problem with weight. I’ve been about 11 stone for years. I seem to be able to eat what I like, but I’ve been sensible. I still play bridge.

“I played rugby when I was in school. I even played against Tony O’Reilly (the late, notable Irish businessman and rugby international). I knew him socially later on, and on one occasion I reminded him that I played rugby against him as a schoolboy, and he said, ‘With who?’ I said Morgan’s School, and he remembered that it was a small, Protestant boarding school, with about 80 students. He was an amazing man. It was just sad the way it ended for him.”

What do you think of the progress Irish rugby has made in recent times?

“I think all that is great, but I also think it is now a very dangerous sport,” says Ib. “I was talking to a very nice woman recently and I heard that her 20-year-old son had got such bad concussion through rugby that he can’t play again. At 20! It’s become such a rough game.”

Of course, being Danish, he must have a grá for soccer!

“I used to play in school before I came to Ireland when I was 15,” he explains. “I could ski, as well. Even when I moved to Ireland I would go skiing with a small group of about five or six of friends, on holiday, twice a year.”

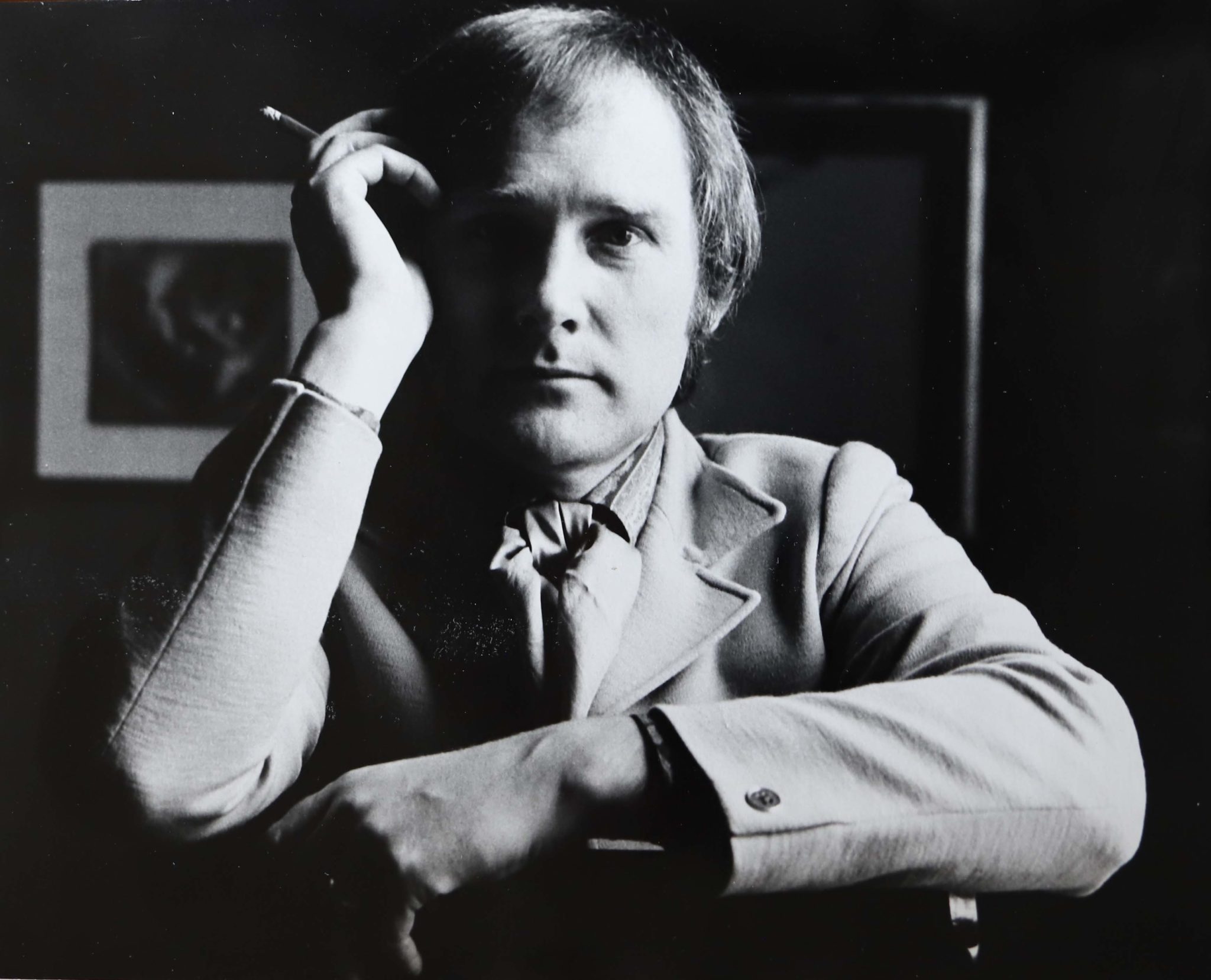

Ib Jorgensen. Credit: Abigail Ring

Jorgensen was married twice, to Patricia Murray (“a very talented artist and designer” with whom he had two children, Lara and Isolin), and to Sonia Rogers. He established his own salon in his early twenties, at one point employing nearly 50 people, so the party lifestyle of sex and drugs and rock’n’roll, often associated with the international fashion scene, was never a priority for him.

“I was committed to what I was doing,” he states, “and was very particular about how items were made. I mean, when I left the Grafton Academy, I knew how to cut a pattern. So I applied to a lovely ladies’ shop (Nicholas O’Dwyer) in Suffolk Street, saying what I had done, and how I admired the shop and the window was very beautiful.

“I got a very curt reply back saying, ‘We don’t employ men’. Around that time, I’d become an Irish citizen, as our family had been here five years, and my father had a very good solicitor who got it through promptly for me, as I wanted to be part of the NAIDA (National Agricultural and Industrial Development Association) fashion show, and you had to be an Irish citizen to do it.

“In any event, I took part in the fashion show, as did the shop I just mentioned, and I won second prize in the coat section and, lo and behold, the shop owner came and bought my coat for his shop! Apparently, the coat sold the same day it was put in the shop, so he asked me could I make another one. By then I had a little workshop in Dame Street, so I said yes.

“I didn’t really know much about couture-making, and that’s why I wanted to work with him, so I made him another of that coat, and another – in the end, I made six! When he came back looking for another one, I said, ‘I’m sorry, but I don’t have time’. That was because my own little business had started doing well and I had my own clients, and those ladies always gave me very good publicity and spread the word.

“Nicholas O’Dwyer then rang me up and said he’d like to take me to lunch, so we met and he offered me a job! He said he’d offer me 10 pounds a week and I pushed it to 11. Young architects, for instance, were getting only five pounds a week at the time.

“A Jewish company in Dublin had closed down, and they had absolutely superb staff who used to make clothes for the Curragh and the Castle. Nicholas had got all those workers in – quite a cute move – so I learnt from them. I already knew about pattern-cutting, but by the time I left after two-and-a-half years, I had learnt about how to assemble beautiful clothes.

“Two people came with me from there and then, gradually, all his people came with me as they saw my business and reputation growing. Then, one day, he was bankrupt. He should have kept me, but he didn’t. I think he subsequently moved to Australia…”

WILL YOU BUY MY BUSINESS?

There were some strange and exhilarating moments along the way. Ib was once part of a fashion show that took place on a jumbo jet…

“Yes,” he shrugs. “It was mainly fashion and other media who were at it. There were some agents, too, and plenty of guests. About 10 designers, including me, were commissioned to make something, using a fabric I normally wouldn’t use. But it was a great success, in that it got a lot of publicity at the time, which was the primary objective of it.”

Among the famous people to wear Ib Jorgensen’s designs were Helen Hayes, the American actress and first woman to win the coveted career EGOT (an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony), and Irish acting legend Siobhan McKenna. President Mary Robinson also wore Jorgensen creations while President of Ireland.

“Myself and Pat Crowley (designer) made her items for her tours abroad,” he explains. “She had a very good figure and fitted into model’s clothes. She has a lot of my clothes and she looks bloody good in them. You might send her five garments and you’d get two back, or something like that, and she – of course – got a discount because we were happy to make these items for her to wear in notable visits to places like Buckingham Palace. She was a good President. She was the first woman in the role, and was internationally recognised and accepted.”

In 1975, and again in 1986, Jorgensen designed separate Aer Lingus uniforms for the all-female team of ‘hostesses’ or ‘stewardesses’, as they were known at the time.

“I found that very interesting,” he recalls. “We used Magee fabrics. There was always a committee of about 12 or 14 girls and I’d present sketches and then they’d choose something and I’d make a model outfit for it. I remember there was one young lady and she questioned everything I did, and I eventually said to her, ‘There’s 14 of you here and I can’t just design it for you!’ But I was very honoured to design the uniforms.”

He designed the first Irish Army Women’s Service Corps uniform in 1980.

“That was another first for me. It came about as I’d already done the Aer Lingus uniforms, so one thing led to another.”

It was unusual for them to ask a highly regarded couturier like yourself to do it.

“It was!” he smiles. “And, in cases like that, I had to do a lot of research on the fabrics and styles of military uniforms, and what was traditional in terms of finding a new look, because you were restricted in the design element. Once I had created the pattern, and I had made the initial one, for them and for the publicity shots, they then put it into production. It was lovely to be recognised, doing things like that.”

Moving to London was perhaps his most exciting adventure. His designs were prominent in outlets like Harrods and Liberty in London, amongst other high-end outlets, and he had his own shop on Sloane Street.

“Anne Heseltine (wife of the Tory grandee Michael Heseltine) was a client, and then also a friend,” he recounts, “and she walked into my shop one day and said, ‘Would you be interested in doing a fashion show, in the Guildhall?’ I said I’d be delighted. That really made my name in London, because she was on a board – there were about 20 of them – and there were up to 800 in the Guildhall. It was a breakthrough for me, because I attracted a lot of those top, top people as clients. Of course, I stopped doing Harrods and the other outlets once I had my own shop there.”

Jorgensen has never felt the temptation to move into high-street fashion, like Paul Costelloe, for instance, whose apparel is also available in shops like Dunnes Stores.

“No, but Paul has done very well with it. I like him, he’s a nice guy,” he says. “He’s been a great success, in that he’s done a top job there. I did have a secondary collection, a boutique collection, which was made for me here in Dublin, which was cut from my patterns and using my fabric. But I was never interested in going the direction Paul went.”

Who have been his own international fashion favourites?

“You’d be influenced by so many things, films, exhibitions and shows,” he avers, “and by whatever other people did, particularly what I’d see when I’d go to Paris, Rome and London – the V&A there was fantastic. In a way, everything is an influence.

“I liked Givenchy. I liked the simplicity. And Missoni. The person I admired more for his development of fashion was Cristobal Balenciaga. It was quite extraordinary the way he could build the fabric like a house. Often, he’d create things without a design, which was quite extraordinary. Beautiful clothes. There was one time when he and Givenchy only showed their collections to one or two American buyers, and that was because designs were being copied overnight.”

Balenciaga was the subject of an acclaimed Disney+ biographical series last year. And, of course, the legendary Hubert Givenchy – who died in France in 2018, aged 91 – had a special connection with the late, great movie, fashion and style icon, Audrey Hepburn.

“As I remember it, after he had dressed her in one of her earlier films, she insisted that he design her clothes henceforth,” Ib says. “The designs were very simple and they suited her –and how! Givenchy was well established before she started making films, but they also became great friends for life. They made some great films together.”

Mention of Audrey Hepburn reminds me of the opening scene in Breakfast At Tiffany’s, which sees her getting out of a taxi at 5am on Fifth Avenue, New York, carrying a paper bag, out of which she takes a take-away coffee cup and a croissant. Incredibly, that was filmed in 1960.

Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast At Tiffany’s

“Yes, it was the shape of things to come. It’s actually extraordinary how ahead they were with that scene. It’s such a common thing now, everybody walking around with a take-away coffee, and so on. Amazing.”

Were there designers he particularly liked in Ireland?

“I admired Irene Gilbert the most. She was a true couturier. She knew how to cut a pattern and drape a dress.”

It was Thurles-born Gilbert who – in 1962 – formed the Irish Haute Couture Group, with Jorgensen, Clodagh Phipps and Neillí Mulcahy.

“Interestingly, towards the end of her time in Dublin, she rang me up and asked me to meet her,” he says. “So, I did and she bought me a drink – I think I had a gin and tonic in those days, now it’s vodka! – and she asked me straight: ‘Will you buy my business?’

“So, I told her that I wouldn’t have the cash to do so and I didn’t need to buy it anyway, because my business was growing and I needed more workers as it was. She obviously thought she wouldn’t lose out by selling to me, so it was a great compliment. I liked Irene. I don’t think she ever sold it, I think she closed it. She’d just had enough.”

Jorgensen recently encountered Clodagh Phipps, who was once based on South Anne Street, where the Ib Jorgensen Gallery is now located.

“Clodagh was a fine designer,” Ib says. “She went into interior design in a big way in New York and has been very successful.”

VIOLENCE CAN HAPPEN ANYWHERE

Ib Jorgensen still keeps an eye on the Irish fashion design sector.

“I listen to the news, of course, and it was good to see the Irish designers being so well received during the recent London Fashion Week. In terms of the international sector, what I find quite difficult is so many of the big fashion house have been bought over and don’t do the clothes that they once did, but they have the famous brand name.”

Of course, over Ib’s long lifetime, there have been seismic social and technological changes in everyday communications, from computerisation to mobile phones. Phone boxes, it seems, are a thing of the past!

“Yes, indeed, and always being so available is a huge change in my time,” he says. “That said, I have a mobile phone, but I don’t like them! They’ve changed the way of living, because you can’t go out without one. It’s ridiculous! I’m not very good with them, but I have to do it. I don’t have a landline at home anymore.”

How did he deal with the Covid pandemic period, and the lockdowns?

“That was shocking,” he admits, “but I coped with it. I went for walks every day. The thing is, you couldn’t fight it, so you just had to get on with things. One has to be positive in such circumstances.”

For a period, Jorgensen opened a highly regarded fine art and design gallery in Molesworth St, Dublin, which moved location several times subsequently. Having retired from fashion in 1994, he then closed the gallery during the pandemic.

“I was tired of opening up in the morning, which was a factor at that time,” he explains. “And, also, it’s a fact that the auction houses are taking most of the custom, so you have to be on your toes. But I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s good for you.”

The Ib Jorgensen Gallery re-opened on South Anne St in 2024, with Jorgensen ever-present inside alongside his daughter Lara and mid-century European glass expert, Deirdre Foley Woods. The gallery specialises in ‘20th Century and Contemporary Art both Irish and Continental, as well as Mid-Century Glass’.

“I decided to take part in a design show in the RDS and Deirdre helped me with that,” he recalls, “and I liked the idea of coming back as I missed it. It’s a very personal business, a relationship business, so that show encouraged me to come back. This shop in South Anne Street was available, so I signed up for a year. It’s tiring, but I’m enjoying it.

“There are some artists I’m supporting in this gallery by showing their works here and selling them – and also other items I invest in myself. I don’t admit to putting anything on the wall that I don’t like!”

Ib Jorgensen reflecting on his designs. Credit: Abigail Ring

Over Ib Jorgensen’s 90 years, he has seen Ireland develop in many ways, not least the transition from an insular Catholic-dominated society to today’s more open country.

“The thing is, Ireland has done well and I’m very happy to be living here,” he says. “I think it’s one of the safest places one could be in – unless you walk around Dublin city centre at midnight (a reference to a recent murder in South Anne St, near his gallery). But one has to be aware that violence can happen anywhere and you have to look out for it. I respect Ireland. And I know it’s up and down with the politics, and so on, but we’ve survived the ride.

“The readjustment that the Catholic Church has undergone here has been huge – and a very good thing. It was so dominant when I came to Ireland first that I recall being described as non-Catholic. We found that strange because in Denmark you don’t discuss religion but, here in Ireland, it was on top of everything. But that has disappeared now.”

And his thoughts on the current US President?

“The world has changed drastically since Trump has come into power for a second time. He has more confidence, too,” he says. “I think it was absolutely shocking the way two world powers (Russia and the US) were talking about another country (Ukraine). Shocking. That would not have happened under any other President. And what he has been saying about Gaza, building a ‘Riviera of the Middle East’! He seems to be completely uncontrollable.

“He comes out with completely stupid, impractical, unworkable so-called ‘solutions’. He is very, very destructive. I’ve been around a long time, and I don’t remember anybody like him.”

Ukrainians have an expression: ‘he’s like ‘a monkey with a grenade’.

“That’s a very good description. I like that!” he laughs.

• Ib Jorgensen: A Fashion Retrospective is located in the National Museum of Ireland – Decorative Arts & History at Collins Barracks, in Dublin. Admission is free, check museum.ie for opening hours. The Jorgensen Gallery is at 21a Anne Street South, Dublin 2.

RELATED

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 09 Jan 26

Second drop of KNEECAP x Bohemian FC jerseys to go on sale today

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 19 Dec 25

Tullamore D.E.W. Distillery: Gift an experience that engages every sense

RELATED

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 15 Dec 25

Bohemian FC and KNEECAP team up for new jersey fundraising for ACLAÍ Palestine

- Competitions

- 12 Dec 25

WIN: Lunch For Two From Forge Wood Fired Pizza

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 12 Dec 25

Minding Creative Minds to hold December meet and greet

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 10 Dec 25

Ticketmaster Gift Card: Give The Gift Of Live

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 09 Dec 25