- Film And TV

- 20 Sep 25

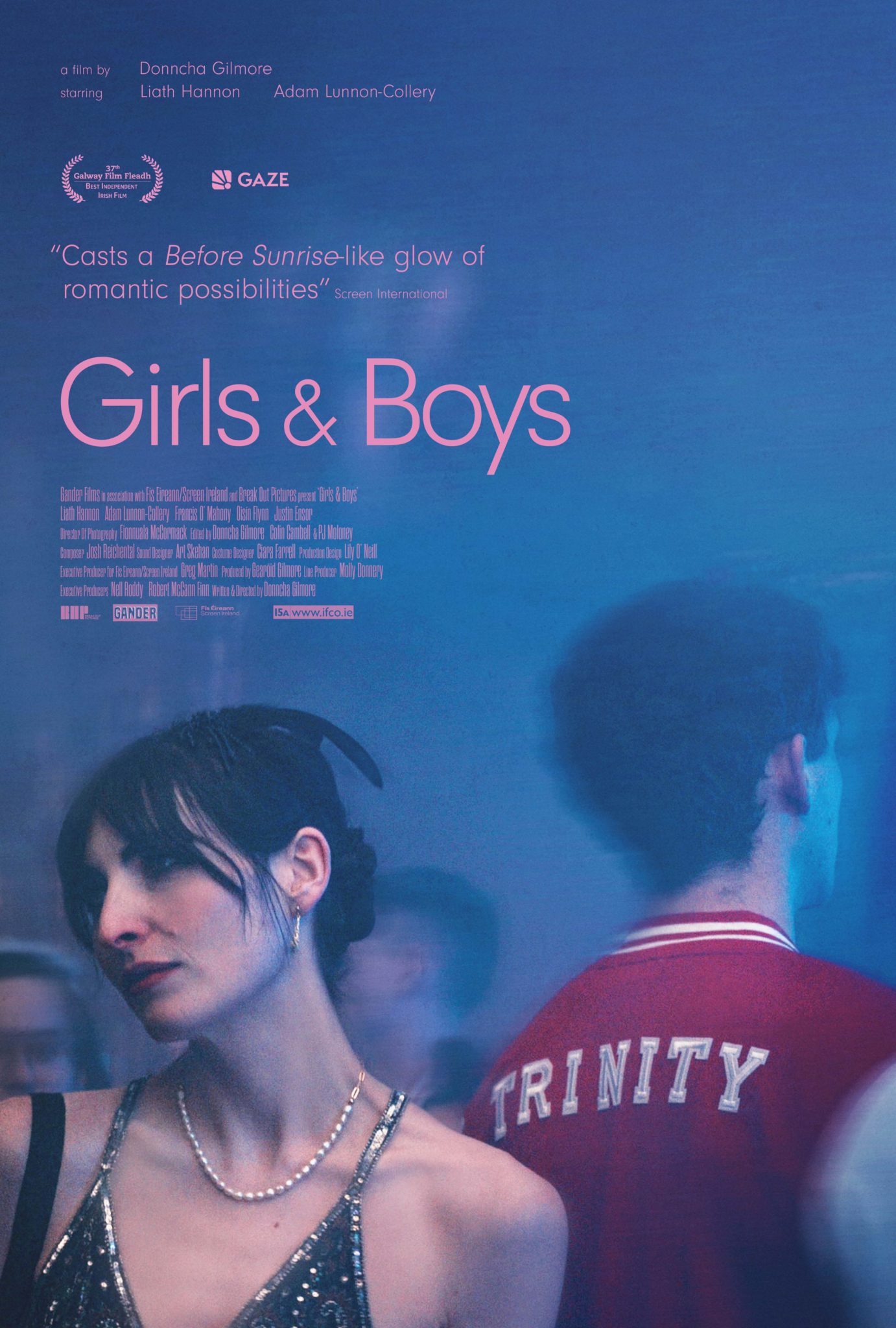

Donncha Gilmore on Girls & Boys: "Their relationship is in the middle of a very gendered world... I wanted to show how those pressures make intimacy more complicated"

Writer-director Donncha Gilmore talks to Roe McDermott about the quietly radical Girls & Boys.

When Girls & Boys premiered at GAZE this summer, it was quickly recognised as a breakthrough in Irish cinema. Written and directed by Donncha Gilmore, the film centres on college students Charlie, played by newcomer Liath Hannon, and Jace (Adam Lunnon-Collery), as they navigate the intensity of love and friendship in Dublin.

It is tender and unflinching, intimate yet expansive, a film that deals with gender and sexuality, but refuses to become an “issue” film. Charlie is trans, but the film shows how everyone in the film is grappling with the constraints of gender, while feeling authentic, natural and intimate.

Gilmore started writing the film when he was a student in 2010, and notes how the landscape around queerness and trans rights has changed – and not for the better.

“Then I felt like we were cresting towards what would eventually become marriage equality,” says the director, “and I thought trans rights were going in the same direction. So when I was working on this film originally, it didn’t seem to me like something that was all that challenging or against the social norm.

“By the time I was rewriting it – 2022 was when the script really broke – I realised that the landscape had changed in those intervening 10 years. There still haven’t been that many films about the topic, and maybe that’s because there’s a fear around it. Particularly in territories like the UK where the conversation has turned very negative.”

An early scene in the film takes place in a locker room, where teenage boys swap explicit photos and boast about sex – an atmosphere of laddish bravado tinged with misogyny and gender policing.

“This is their version of male bonding, of friendship,” says the Gilmore. “When I was in dressing rooms in football as a young person, it was worse than that. What’s in the film is quite light compared to what I observed myself many times.”

From that beginning, the pressure of masculinity shadows every character.

“Something I always wanted to be in the film was this idea of straight homophobia that affects straight men,” Gilmore says. “It’s a strange thing to think of, but I’ve seen it. They have their own experience of it, the constraints it places on them.”

As a young trans woman, Charlie struggles with feelings of self-worth, making some bad decisions and allowing men to treat her badly. But she’s not a victim. She’s intelligent, creative, funny, sparky, loyal, disloyal – a deeply human, multifaceted person who, like all the characters, is stumbling her way through life.

The character of Charlie was developed through workshops and conversations between Gilmore and Hannon, evolving from page to screen. Hannon describes the process as collaborative.

“She wasn’t fixed when I first came to her. It was about finding where her strength came from, how she would hold her own in spaces where she was underestimated.”

The film feels quietly radical in its refusal to engage in well-worn stereotypes. While it centres on a trans character, it refuses tropes like endless suffering, focus on the body or simple, reductive narratives. It’s a deeply human story with universal themes as well as nuance and complexity.

“All the characters are imperfect, oscillating between right and wrong,” says Gilmore. “That felt important to me – not making anyone a saint or a villain, but showing how they’re trying to figure it out.”

Much of the film unfolds in long, conversational scenes between Charlie and Adam, their intimacy reminiscent of Before Sunrise or Normal People. Gilmore acknowledges those echoes but is clear about his aims.

“There are those influences, but I wanted to subvert them. It’s not just about two people in a bubble. Their relationship is in the middle of a very gendered world, and I wanted to show how those pressures intrude, how they make intimacy more complicated. And I wanted the film to go to darker places as well.”

That interplay between the personal and the social is what Hannon believes gives the film its resonance. She recalls how audiences have spoken to her after screenings.

“There’s a very traumatic thing that often happens with queer people, where they start to lose their friends during adolescence,” says the director. “People have told me the film really made them want to revisit those friendships, to think about love and loss, and about how much the idea of who they’re supposed to be impacts the person they actually want to be.

“What the film accepts so beautifully is that this is something people really grapple with, but also that the characters decide not to live under that pressure anymore. They find joy in that choice, and that possibility is what I hope people take from it.”

If the emotional currents of Girls & Boys feel universal, the geography and sound is unmistakably Dublin, with a soundtrack full of contemporary Irish acts, woven into the film not as decoration but as part of its texture.

“It mattered that it wasn’t generic,” says Gilmore. “These are the songs people in Dublin are actually listening to. They make the world feel lived in.”

Girls & Boys is in cinemas out now

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 01 Feb 26

Films To Look Forward To In 2026

- Film And TV

- 30 Jan 26

Disney+ unveil trailer for second season of Paradise

- Film And TV

- 30 Jan 26

FILM OF THE WEEK: Is This Thing On?

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 30 Jan 26

Beatles biopics first look photos shared

- Film And TV

- 29 Jan 26

Screen Ireland announces Power Ballad, The Lost Children of Tuam for 2026

- Film And TV

- 29 Jan 26

Barry Keoghan reveals Ringo Starr haircut ahead of Beatles biopic premiere

- Film And TV

- 27 Jan 26