- Opinion

- 21 Sep 25

Catherine Connolly: "It takes nearly a lifetime to understand, actually, the importance of a mother and the consequences of losing her"

As we go to press, there are only three candidates certain to contest the upcoming Presidential election. One of them is a relatively little known independent TD, who is supported by the parties of the left – the Social Democrats, People Before Profit and the Labour Party. Her name is Catherine Connolly. But who is she? And what does she really stand for?

To date, the upcoming Presidential election seems absurdly boring compared to recent races.

There has, of course, been abundant silly season talk about the possibility of so-called celebrity candidates running for the Áras, with the businessman Gareth Sheridan also having officially put his hat in the ring. In fact, you can hardly open a newspaper without someone claiming that they’ve been asked by their friends “Why don’t you give it a go?”

But, as things stand, only a few serious political candidates have been confirmed. The likeable Heather Humphries has replaced Mairead McGuinness – who withdrew for health reasons – as Fine Gael’s candidate; meanwhile, the Social Democrats, Labour and People Before Profit have all declared their support for the independent Galway West TD, Catherine Connolly.

As a local councillor, Connolly was selected as Mayor of Galway in 2004. She was first elected to the Dáil in 2016 and made history in 2020, when she became the first ever female TD to become Leas-Cheann Comhairle.

Catherine is a barrister, having studied at Galway University and the King’s Inn, Dublin. She is also a qualified psychologist, having done her Master’s degree in the University of Leeds.

“Somewhere along the line, I started doing an LLB and it was a turning point in my life. I did it in the evening time,” she tells Hot Press.

“I suppose I would have gone to college and did my best to avoid studying,” she adds. “The last thing you wanted to be was a nerd. You were supposed to pass exams without doing too much study. I would have called myself a procrastinator for lots of reasons. I’ve never used the word lazy about myself but procrastinator. The LLB changed that, and I realised it was wonderful. I realised that it was interesting.”

The question now is, could her run for the presidency also be a major changing point in her life? And will voters find her an interesting enough candidate?

Let’s see what we can find out…

Growing up, were there tough times involved?

There were tough times. I’m part of a big family: 14 in the family, seven boys and seven girls. We took it for granted. That’s the way we grew up.

I’d imagine it was cramped.

I don’t use words like cramped. I think I came from a privileged background. I came from a wonderful father and mother. Unfortunately, my mother died when we were young. My father had to step in, and subsequently, an older sister and then another sister. And I think we all considered that we were privileged in so many ways, because we got to know life from so many different views. We knew joy and we knew sadness, to give us a unique perspective.

How old were you when your mother died?

Nine. I had a number of siblings younger than that, so the age range went from one to 21.

I imagine it had a profound effect on you.

Absolutely profound, a lifelong effect. It takes nearly a lifetime to understand, actually, the importance of a mother and the consequences of losing her. I suppose we all dealt with that very differently. I certainly, for a while, had the feeling that it was better to be without a mother, in the sense that was my coping mechanism. There was nobody to tell you how to wear your coat or how to dress, and so on. But as life went on, I realised that was a coping mechanism that served me to a point, but not well.

Can I ask how your mother passed away?

It was very sudden. I think she was at the pictures on a Friday night and she was dead on Saturday. So, we were never quite sure what happened. She had asthma – but 43! At that time, there was no post-mortem, I think. Maybe my dad said no, I don’t know, but it was quite sudden. She had been sick with asthma, and she had 14 children, but she was very much a woman’s personality, let me tell you.

Was motherhood made more precious for you, because of losing your own mother so early?

It was. But it was something I didn’t rush into. I waited and it was beautiful. Looking back, I wish I spent more time [with them]. I did spend a lot of time with them, but I had changed over to law and when you start in law and you’re not connected, there isn’t much work. So I was trying to keep my hand in and do other things and look after my children as well.

Catherine Connolly protesting outside the Dáil with Oireachtas Broadcast Workers. Copyright Abigail Ring/ hotpress.com

Were you political in your younger years?

I wasn’t political in my teens at all. I’m a latecomer to politics in one sense. But in another sense, I was very active in the community. I was part of a group called the Shantalla Youth Group. I remember my sister, it was an ongoing joke, she was doing all the work at home while I was saving the world. We collected money when we were young for a basketball court in Shantalla. And that facility is still there and it’s upgraded. And we visited houses. Would you believe I was part of the Legion of Mary?

So, are you religious?

Not really. My father was religious and a Catholic, and we were brought up as Catholics. But I mentioned the Legion of Mary by way of saying that’s where we learned really to think beyond ourselves. But of course, we were more interested in the Legion of Mary for going to discos – they were called hops at the time – and meeting boys. And learning about the world outside of ourselves, I think, was the biggest lesson I got from religion.

Did you ever say to your father about religion, “Hold on a second…”

We gave my father a very hard time over religion. All 14 of us. My father lived until he was 90. He was a man that grew and changed and learned. And I think he’s given us that, a lifelong love of learning. And, I think, the knowledge that we have to continue to learn all of the time. And the more you learn, the more you realise, the less you know.

Do you believe in heaven and hell?

No, I don’t believe in heaven and hell. But I’ve lost a number of siblings in the last number of years, in addition to my father and my mother. Of course, part of you always wants to think you’ll see them again. But they are with me. They’re guiding me. I think that’s heaven for me, that they’re with me. So, when I feel this is too much, I hear my sister’s voice say, “Take a little rest and start again.”

Growing up, were you interested in music?

I was, yeah. We loved music. It was a funny house in the sense that the music was quite mixed. We loved classical music. I remember playing La Traviata. We knew all the words going back years ago of Joe Dolan, Dickie Rock. We grew up with that. And when we got together as siblings later – I had siblings in Sligo, in London – we’d always play music while we were chatting and having cups of tea.

Would you have been aware of punk rock music at the time?

Not really. But lately, I went to a [punk] film that was absolutely brilliant. It was Frank Shouldice’s film Once We Were Punks. And I thought, “God, I’d have no interest in that.” But it was a wonderful documentary. And the backdrop, of course, was Captain Kelly and the arms trial going back to the ’70s. I had a boyfriend who was a little older and he was very tuned into it. One of Captain Kelly’s children, his son, was the singer in that punk band. It was an interesting introduction to punk. They did admit they had no talent at the time.

Would you have read Hot Press?

I would. Yeah, absolutely. And I would have been familiar with different articles that made more publicity than others.

And who were your heroes at the time?

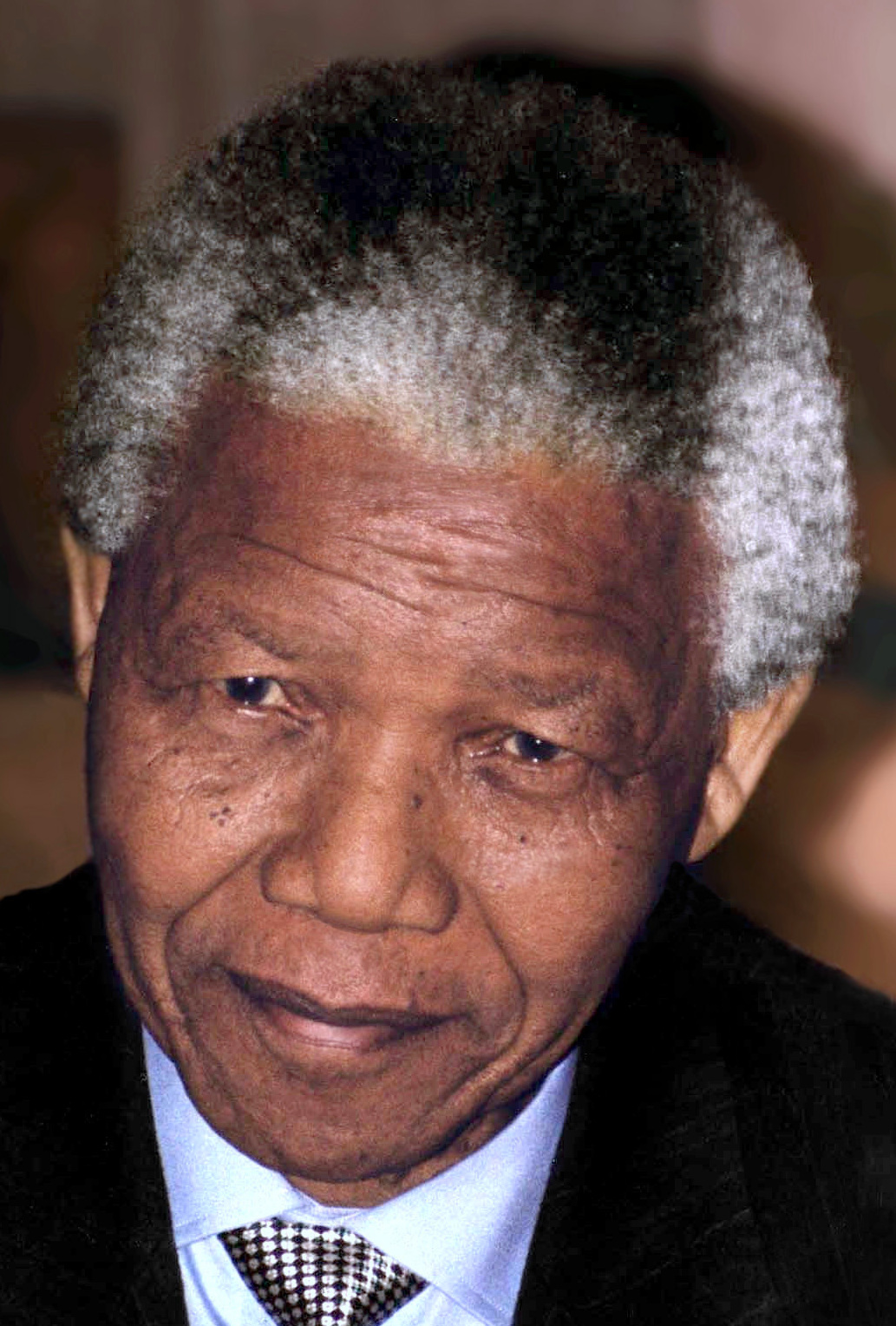

I was never conscious of having a hero or a band that was a hero. I loved music. But I didn’t have a hero in that world. I suppose, at home, my father was our hero. My sisters who took over. We didn’t express that at the time, but looking back, they were our heroes. Then going forward, Nelson Mandela shone out, and when I read about Rosa Parks in 1955 and what she did, they became heroes. There have been other figures. Martin Luther King. But growing up, I wouldn’t have had it in my head who was a hero.

Nelson Mandela

Were books important to you?

I suppose we were busy surviving and reading and educating ourselves. I would have been very much influenced by books I read at the time. You know, Simone de Beauvoir. Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire. And I’m back looking at that book again. But we just read them and ingested them. And really, they formed me and my siblings.

You’ve been described as a Republican. Did you support the Provisional IRA’s campaign in the North in the ’70s?

No, no, no, I did not. And I wasn’t even active in the ’70s. However, I was aware very much of what was happening in the North of Ireland through a relationship that I had at the time. But also, because the refugees came to Galway. So, we were acutely aware when I was a teenager of the refugees staying in various places, including St Mary’s College in Galway. And I would have gone up to help them. And I was very aware of the sense of desperation that they felt. And the loss. And that they were simply coming down, in the truest sense, for refuge. Would I have been political? No. Political in the sense of expressing views? I would not. But I would have been acutely aware of what was going on in Northern Ireland.

You mentioned Nelson Mandela. Would you, for example, put Martin McGuinness in the same category?

I have the greatest respect for what Martin McGuinness and Gerry Adams did in terms of the peace process. Absolutely. There couldn’t have been a peace process without them.

But before that, you wouldn’t have been a supporter?

No, no, no, no.

What’s your position on a united Ireland?

I think we have to unite. We’re a tiny country. We should have never been divided. It was detrimental to the country and to the people. And I would hope that we could do that with consent, while respecting all sides and all groups. It doesn’t make sense to have a divided country.

Have you spent time over the border?

I’ve been up there in the last number of years, quietly, as a chair of the Irish [Language, the Gaeltacht and the Islands] Committee. So, I always, on many of my trips, when I went over the border, felt that it’s as if we’ve cut off a limb from our body. And psychologically and politically, it’s just wrong. And I hope that I see United Ireland in due course.

You seem to be very anti-EU. Would that be right?

No, that would be very wrong. I’m very anti the militarisation of the EU. And I’m anti the neo-liberal agenda that permeates the treaties. I did a semester in a German college. My brother – who is now dead – married a German woman. My two sisters went to Germany. So, I know exactly what it means to be a European. There’s a difference between a European and valuing European values and the copper-fastening of a military-industrial complex. They’re two very different things.

But hasn’t the huge geopolitical shift of the past few years not placed an enormous question mark over the whole idea of neutrality?

Our neutrality? I think quite the opposite. The shift, as you were describing it, has really reinforced my conviction that we need to be an active, neutral country more than ever, that we need to use our neutrality proactively.

How can we be neutral about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the threat it represents to all the former Soviet Union states?

The invasion of Ukraine was illegal. What’s happening in Gaza is utterly appalling. What we’re not even talking about in the Sudan is just words failing me. But hold to a neutrality that’s active, that speaks truth to power, no matter where that is, whether it’s Putin or whether it’s Israel or whether it’s America. We need to speak truth to power. There’s nothing to be gained by a country like Ireland that has a proud tradition of neutrality and peacekeeping, giving that up. And there’s everything to be gained by using our voice to promote peace in the world.

Including denouncing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine?

I have never, ever hesitated in my condemnation of the illegal invasion of Ukraine. So, if we’re going to have credibility, we must call out, like I said, the abuse of power, no matter where that happens. And we must be a voice for peace. In fact, our constitution obligates us to be a voice for peace and to seek out peaceful solutions to problems.

You seem to be close to Clare Daly and Mick Wallace?

I have the greatest of respect for Clare Daly and Mick Wallace. They were there when I came into the Dáil in 2016, and we formed a technical group.

They are often accused of being apologists for Putin and Russia. What would you say to Clare and Mick on that issue?

I think that has been a very dangerous narrative that has been promoted by well-placed articles in so-called respectable papers – and I think it’s a very dangerous narrative. I have never heard either of them not condemn the illegal invasion of Russia, ever. Ever. Ever. So one has to ask then, what is this narrative about? What has been achieved here with this narrative?

What has been achieved?

As a former psychologist, that narrative frightens me completely. It frightens me that we could single out an individual or a second individual for a particular purpose to demonise them. To reduce what they’re saying is totally unacceptable to me. I think they’ve done great work – Clare Daly, in relation to maternity deaths and asking for postmortems automatically; in relation to corruption at the time in the Gardai; and many, many other issues. I could only admire them.

Are you happy that the President requires permission of the government and, in effect, the Department of Foreign Affairs to travel outside of Ireland?

Yeah, it seems a little bit dated, but it is part of the constitution, and I respect the constitution. I’m a democrat to my fingertips, really. And we have a democracy.

Some people see it as being extremely arrogant for anyone to think, “I should be President of Ireland.”

Yes. I agree with those people, actually. And the hardest part of this process for me was making that decision and fighting those voices in my own head: “Who are you? Who do you think you are?” I would say that was the hardest part of the process, coming to that decision. And I fully understand why people would say that. But I think my experience – I’ve had the privilege of working in different roles, and I’ve the privilege of being in the Dáil. I’ve always looked on my role as a privilege to serve the people. And I think in that role as President, you’re there to serve the people and reflect their values as best you can and as best you can interpret them. This country could be leading the world in terms of peace, being a voice for peace, a trusted voice in diplomatic relations, and then in terms of being a shining light for climate change.

Candidates often quote Seamus Heaney.

I know the Seamus Heaney poem, and I know that his family are sick and tired of people misquoting his poetry. So, I’m not even going to attempt it. But his ‘From the Republic of Conscience’ talks about those stepping into public office. They should seek to atone, seek to atone for the arrogance of seeking public office. They’re not the precise words, but that’s the gist of it. And I think it’s uppermost in my mind to keep that. That one should seek to atone on a regular basis for the arrogance of seeking public office. I suppose when I ask what has led me [here], I think we’re at a crucial point in our destiny. And we need to decide where is our destination as a country? Where is it that we want to head?

Which is?

My experience tells me that people want us to use our voices for peace and for a different type of world to make words mean something. So, we declare a climate emergency and a biodiversity emergency. Then we need to reflect that, not just in words, but in actions. And we really need to have transformative action in the country.

Catherine Connolly at Leinster House on August 26th, 2025. Copyright Abigail Ring/ hotpress.com

So, when did you decide, “Yes, I am an ideal candidate for the role?”

I’m never comfortable with those words. And I think really I would see myself as part of a movement, a movement that people realise the power they have. I mean, just if we take Palestine again, and I’m not ignoring Sudan, which we are actually ignoring, but Palestine, people are saying, stop this. There’s a movement to say, “Don’t do this in our name.” It’s the same with climate change. Stop, let’s have the transformative action that’s necessary. So, I would see myself as part of a movement to reflect what people are saying on the ground. We have no choice but to do things differently. I would hope I would draw on my own experience as a mother of two children, as someone who came from a large family, to realise that we can actually change.

So what qualifies you, say, compared to someone like Mary Robinson to be President?

Again, I wouldn’t compare. I think Mary Robinson was a great President. I think Michael D. has been very good. He’s been extremely courageous, and it was necessary to speak out. I absolutely respect what he did. So, I’m coming forward based on my experience, in the different roles I’ve had. I think I’d be in a position to reflect the values of the country. I think the role of the Presidency is very different to the Seanad and the Dáil. They’re all important, they’re all part of a trinity.

You weren’t always at idem with Michael D.

I’ve always respected Michael D. We parted ways with the party for political reasons. But I have publicly praised Michael D. And it’s always been my way, if the issue is right, I will support it, whether that’s right or left. I supported the Labour Party in the Dáil and different private members’ bills they’ve brought forward. I’d like to think of myself as an issues person. I don’t talk about the Labour Party in terms of falling out. I moved on. I have articulated why in the past. And I don’t think it’s relevant in the sense to this election at all.

Michael D Higgins at Áras an Uachtaráin. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Didn’t you accuse Labour – who are now backing you for the Presidency – of having lost its soul?

I did. That’s been put to me recently in many interviews, and I absolutely did. And that’s what I felt. There was a time to seize leadership in Ireland, and lead. The solutions to our problems are there. And they’re there with the people on the ground. And there’s a disconnect between governments generally and the people on the ground. I would have had an acute sense of frustration over the years, seeing the solutions that weren’t being implemented. And seeing good people lose hope and move on, or worn out by the system.

Would you like Sinn Féin to support your candidacy?

Yeah, I would like as much support as I can get. I met with the Green Party, and I’ve talked to Sinn Féin. They have their own internal processes, and they’re going through those processes. As an independent, I needed to declare. And I’m happy that I declared, although some people said I declared too early. But once I made my decision, I had to stand up, be counted, and say to people, “I am standing, this is who I am, this is what I stand for.”

How will you finance the campaign?

I wouldn’t have the finances – the finances are major. If you were to think of the cost of this election, you wouldn’t stand. There’s no way we can finance this. So what I’m saying to people is, anything from a euro to €5 is equally as important to me as €20 or €50. So I’ve appealed to people to come on board. I’m not doing a promotion here. What I’m saying is, it’s a movement. It’s a movement that people need to be involved, need their voice heard. And certainly, the financial challenge is an ongoing challenge.

There is much talk of many so-called celebrities with deep pockets running for the Presidency.

It upset me to listen to some of the debates, the circular arguments, where it’s a bit of a game, and which celebrity is now going to stand, and “We don’t need a politician.” We were demeaning the role of the Presidency, in my opinion, with that type of argument. And it was one of the things that finally led to me making the decision to say, “No, the role of Presidency is extremely important, directly elected by the people of Ireland, and to be respected, and to rise to the challenge as best I can.”

What about Conor McGregor saying he wants to be President? [McGregor has since stated that he 'will not contest this election']

I’m speechless at the idea that he thinks he might stand for the Presidency. But we let the councils decide that. Certainly, I’m not happy, but you’re entitled to seek a nomination, and hopefully, where he seeks it, the people will see what he’s done.

You supported Gemma O’Doherty to run for the Presidency. Did you really think that she’d make a better president than Michael D. Higgins at the time?

No, I did not. But I supported it. You know, different people come to you as a TD seeking nominations, in the manner that I’ve gone to people seeking nominations. And I nominated her at the time. She did some good work. I was nominating her to give her a chance to let people decide. As it turns out, she didn’t get the nominations. But she got a range of nominations from different people.

A lot of Hot Press readers would be wondering: what qualities did you see in Gemma O’Doherty that recommended her to you specifically?

Yeah, it’s a good question. I suppose at the time, it was the work she had done as a journalist. Some of the investigative work she had done in relation to the guards, in relation to the situation in Donegal.

In retrospect, do you regret it?

I don’t regret it. I did it at the time. I mean, if it was a few years later and the views that she’s since expressed, I’d absolutely not nominate her.

In 2004, you supported Dana as a candidate. Did you really think she would have been a good President?

You see, it’s a strange thing, nominations. Dana went for Europe at the time and people came up to me and they said, “I gave you my No.1 [for the Galway City Council election], and I gave Dana No.1.” And I would have seen us as at opposite ends of the spectrum. And yet, people were giving me No.1 and were giving Dana No.1. And I always use that to remind me of the complexity of people. And she deserved a nomination to stand, you know. Would I support her politically? No, I describe myself as the opposite end of the spectrum. Would I agree with her? No.

Some people might say that supporting two such unsuitable candidates, in many ways, will put a very big cloud over your judgment.

Yeah, I think people are entitled to say that. In fact, I don’t agree with them. I did what I did. I think the Presidency is a different role. It’s a nomination process. And sometimes you reflect, people are entitled to be nominated, to let people make a decision, to give people the choice. It’s a direct election from the people and you let the people speak. Yeah, I think Dana got a very hard time. Actually, I think she suffered dreadfully. I don’t agree with Dana at all. But I certainly wouldn’t agree with the tough time she got and the allegations that were made in relation to her brother. I think that was very wrong. You know, we need to draw people together.

But if people don’t agree, they don’t agree.

What’s a cause for concern, is the division on occasion between urban and rural. It’s a very worrying divide. So, I would look on myself as a unifying candidate, to draw people together and to recognise the complexity, while not moving from my values. I’d rather lose a vote than move from what I value as important. But at the same time, I think my experience would allow me to draw on what’s best in people to take the best.

You’ve expressed your opposition to US military transport landing at Shannon for refuelling. As President, what would you have to say about that?

I will never change from saying we should not be allowing Shannon airport to be used. It’s just an obscenity. However, as a President, you have a role and you have to do that role as best you can within the constitution, and comply with the law. I think I’ve come to the point where I’m able to do that. And all we can do is our best in each role and to use the role as wisely as possible while staying within the constitution and the law.

How would you act on the situation in Gaza?

I’m near tears in relation to Gaza. It’s just so awful what is happening in Gaza in our name. And I think it’s a turning point. We’ve reached a new low in terms of warfare. Warfare is always bad. So as President, obviously I will use my voice for peace in every way I can, to promote peace in the world and peaceful solutions.

I get the impression, if you were President, you wouldn’t be very comfortable having to shake hands with Donald Trump.

There are many people I wouldn’t be happy shaking hands with now or as President, and I shook many hands as Leas-Cheann Comhairle. We had many visiting dignitaries in the Dáil that I didn’t feel comfortable with. But it’s human to shake hands. It’s also human to say I don’t agree and what you’re doing is wrong. You can do the two things. As the President, you do it in a slightly different way.

Donald Trump. Illustration: Julia Lee

So how would you deal, as President, with how Ireland should respond to Trump’s attack on democracy in the USA?

It’s really very worrying what’s happening. Our government needs to realise it actually. I’m not sure that they do because they’re part of an EU that has just agreed a tariff deal and they’re hailing it as marvellous – and we don’t know the details! We have the headlines and it would seem we’re going to buy more military and more arms from America. We’re going to buy more energy. It’s extremely worrying what’s happening. The international human rights whole structure has been undermined. The UN has been undermined. It would seem to me that the arms industry are so powerful that they are determining policy.

But as President, you’d have to be careful how you spoke about Trump.

Again, I emphasise I’m speaking as a human being, as a TD. The role of President is laid out in the constitution and by law, and I’m fully conscious. I spent 20 years working as a barrister. You’re there to serve. You take a vow to dedicate yourself to serve the welfare of the people. And I’d be interested in exploring that, how to use that to speak, to be there serving the welfare of the people.

Have you ever smoked marijuana?

No [laughs], not that I’m aware of anyway. I take no high moral ground for this. I wasn’t a smoker. We were big into sport and we’d read books. I had no interest in it, really.

What about the legalisation of cannabis and the criminalisation of other drugs?

I think Gino Kenny did tremendous work on that before [with his cannabis bill]. The independent female senator, the name just escapes me, she’s done tremendous work in the Dáil in relation to the decriminalisation of drugs. I think drugs are a health issue.

Which means…

I think there are two aspects. There’s the criminal aspect and drug-pushing, and then there’s the possession of drugs. I think it’s an addiction and I think we need to look at it within a health framework. I think that’s been articulated by people much more knowledgeable than me on this subject. The criminalisation of drugs hasn’t worked. Making criminals out of people who use drugs like cannabis it’s just not a way to do it. Am I comfortable with drugs? Not at all, but I’ve tried to keep up and read whatever I can – and the criminalisation of drugs and looking at it through that framework is not successful.

What is your stance on euthanasia?

Again, it was Gino who brought [forward] that bill. I struggled with that, I have to tell you. I struggled with it because of the misuse that could be made of it. Again, I read everything I could and the various reports and I suppose I say to myself, “Who am I to say you can’t make that decision? Who am I to say my sibling can’t make that decision?” I don’t think I have the right to make that decision for you or for my sister or for my mother, but I would really be strong on safeguards. So, safeguards would be huge for me in relation to ensuring there was no misuse of the legislation.

Finally, can you speak Irish?

Actually, as mayor, I went to Lorient and I was ashamed because I was able to make a speech in Irish and afterwards Raidió na Gaeltachta wanted to interview me and I said no. They said, “But you just made a speech!” I was able, from school, to read Irish but I wasn’t able to do a live interview. I made a promise to myself. I started with my children and reading to them. Then, because the university was in Galway, I went back and did a diploma in Irish and then went back again and did a diploma in translation. It was all there at my doorstep. I had reached the point where I wanted to, and I had reached the point where I wanted to do away with shame. No more shame.