- Film And TV

- 20 Aug 25

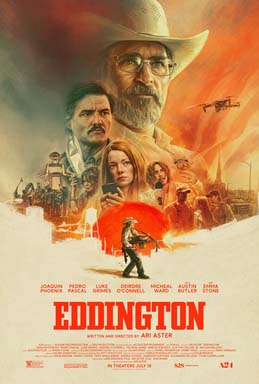

Eddington director Ari Aster: “You’ve got a bunch of people who are very scared and alone, and grasping at autonomy and agency when they know they don’t have it"

Celebrated for the cult classics Hereditary and Midsommar, director Ari Aster now returns with Eddington, which explores the socio-political convulsions America experienced in 2020.

Ari Aster is not here to give you answers. He never really has been.

Whether it’s the grief-soaked dread of Hereditary, the sun-drenched horror of Midsommar, or the surreal anxiety odyssey Beau Is Afraid, his films have always sidestepped easy resolutions. With Eddington, his latest and most overtly political work yet, Aster turns his lens on America in 2020 – a landscape fragmented by isolation, paranoia, and a desperate search for meaning.

Covid fear and conspiracies are rampant, #BlackLivesMatter protests are breaking out all over the country following incidents of police brutality, and people are reading completely different information online, becoming more and more ensconced in their echo chambers. Eddington is a modern western, where the six-shooters have been replaced by smartphones.

“The film is kind of about that,” says Aster. “A bunch of people who know something is wrong, and none of them can agree what that thing is. And that’s where I started from: that feeling of living in a kind of social vertigo, where everything felt off-kilter and unreal, but no one could agree on the source of the dissonance.”

Set in the fictional town of Eddington, New Mexico, during the early days of the pandemic, the story pits Sheriff Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix) against incumbent Mayor Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal), in a tense battle over a proposed AI data centre.

As conspiracy theories run rampant, familial bonds erode, and neighbours turn against each other, Eddington becomes less a parable than a portrait – equal parts satire, elegy and indictment.

“I think what was lost was a common ground we could all stand on,” says Aster. “We’re living in a world right now where we’re all living in different versions of reality, and we distrust anything and anyone that kind of contradicts what we believe, or stands outside our bubble of certainty. That’s terrifying, because the people leading us don’t even seem to believe in a future. Or at least they don’t believe in our place in it.”

For Aster, Eddington is not simply about 2020 – it was written during it.

“I started writing this, I would say, at the peak,” he recalls. “When the fever kind of reached its highest pitch. I was living in New Mexico, where I grew up, but I was isolated. There were people in my life – close people – who I could no longer talk to, not really.

“Politically, emotionally, we were just not living in the same world. Our fears were different. Our anger was directed in totally different directions. And it was – and is – heartbreaking.”

The phones are everywhere in Eddington – not as incidental props, but as sinister presences. Joaquin Phoenix’s character reaches for his when he feels undermined by those around him. His troubled wife Louise (Emma Stone) uses it to find a guru (Austin Butler), who promises to hold answers to unacknowledged trauma.

Louise’s mother Dawn (Deirdre O’Connell) obsesses over conspiracy theories. White woke activists use it to promote their cause, and themselves. Townsfolk film each other constantly, as forms of punishment, shame and surveillance. People record each other, upload posts and photos as a form of self-performativity or aggression against the other, and become more entrenched in divisive rhetoric.

Whenever a character feels out of control or vulnerable, they reach for their phone to give themselves the illusion of power. It’s relentless, and never provides relief.

“We all know what they’re doing to us, and yet we keep using them,” Aster says. “I think we’re already sick with the phone, but I wanted to make that feeling literal. Not just as background detail, but something foregrounded – something you feel in your gut. I wanted to make the screen feel malevolent, to make you queasy every time someone looks at it.”

Aster sees the problem not as accidental, but engineered.

“We’ve been successfully divided,” he says. “And I don’t think that’s just some innocent consequence of, ‘Oops, social media got out of hand.’ No. Social media was harnessed. It was weaponised by very real people and systems and used to split us apart, to fortress us off from one another. That’s happening at the national level, with countries, and it’s happening at the individual level too.”

And so the story’s architecture reflects that, showing fragmented perspectives passed through a common digital filter.

EVERY CRISIS

“The film is about a data centre being built,” says Aster. “That’s not just a backdrop, it’s kind of the whole metaphor. These stories, these people – they’re data. They’re inputs being sucked into this giant wooden wheel. That’s how I saw it, this structure that consumes every emotional crisis, every tragedy, every ideology, and uses it as content.”

Yet Eddington isn’t trying to play the moral referee. It doesn’t offer a neat binary between heroes and villains. Conservatives, racists and conspiracy theorists are criticised but also sometimes humanised, while progressives are seen as exhausting and patronising with their performative rhetoric.

That ambiguity has led some early viewers to question whether the film risks a kind of both-sides-ism, suggesting equivalence between well-meaning progressives and extremist ideologues or violent racists.

Aster is firm on this point.

“I don’t think that’s quite fair,” he says. “Because, yes, one side might be cast in a critical light, and shown as badgering or hypocritical or annoying. But the other side is doing real harm. They’re killing people.

They’re framing people. They’re ruining lives. So to suggest that I’m treating those things as equal feels disingenuous.

“The film is a satire, I guess, but what it’s satirising isn’t a single group. It’s the environment. And I think there are certain people who have a problem with the film, because it doesn’t take a clear enough political stance for them, or they think I don’t make a partisan enough argument. But for me, the film is about the fact that we can’t reach each other.”

The director teases out the point further.

“To make a partisan film would only reach the choir that we reach,” he says. “And that’s just too narrow, given what the film is about and what I’m trying to get at. Which again is the environment, the landscape, and asking how the hell have we gotten here? And how can we reach each other again, you know?

“I’m not a politician, I’m a filmmaker. So I’m more interested in the questions than proselytising about the solution.”

Even in the film’s collaboration with Joaquin Phoenix – a reunion after Beau Is Afraid – the focus is on dynamic instability.

“There’s a rebellious side to Joaquin that kind of doesn’t want to fall into anything that I wrote,” says Aster. “I think that’s what I find very inspiring and exciting… He challenges the material in a way that refreshes things for me. Sometimes we’d be on set, and he’d say a scene felt too clear, too easy. He didn’t want it to resolve in a way that felt pat or reductive.

“There are writers and directors who just want you to stand on your mark and say the lines. I might have been that on my first films. But Joaquin resists that. He electrifies the material. And what he does with the character of Joe Cross, the sheriff – it’s special. It’s vulnerable and weird and angry and sweet. It’s unlike anything he’s done before.”

Eddington is filled with characters like Joe: grasping for agency, desperate to feel in control of their lives.

SOME SOLIDARITY

“You’ve got a bunch of people who are very scared and alone, and grasping at autonomy and agency when they know they don’t have it,” says Aster. “They feel powerless. They are powerless. And they’ve been turned against each other... That’s what the movie is really about. Our neighbour is not our enemy.”

Even if it feels, increasingly, like we’ve all forgotten that. It’s interesting how quickly society has seemed eager to forget Covid, and Eddington urges us to remember the pain of that time, how physically separated we all were – and to remind us that isolating ourselves from each other, emotionally and politically, is another form of collective trauma we need to acknowledge and address.

Like all of Aster’s movies, there is darkness and pitch black humour amidst the violence and social commentary. And as with his other work, viewers will likely either love it or hate it – but hopefully they’ll discuss it.

“I hope,” Aster says finally, “that there can be some solidarity in just sitting back together and acknowledging the insanity of this moment. Not to laugh at it, exactly. But to say: this is real. This happened. And we are all still here.”

• Eddington is in cinemas from August 22.

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 20 Aug 25

Channel 4 announces Army of Shadows series written by Ronan Bennett

- Film And TV

- 19 Aug 25

Ozzy Osbourne documentary pulled from BBC schedule due to family request

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 19 Aug 25

Numerous Irish films to be showcased at Edinburgh International Film Festival

- Film And TV

- 18 Aug 25

Prime Video releases first look at Fallout season two

- Film And TV

- 18 Aug 25

Netflix announces release for House Of Guinness and shares first look images

- Film And TV

- 15 Aug 25