- Opinion

- 30 Jun 25

The Environmental Crisis: We Need To Act Now Or Regret It Forever

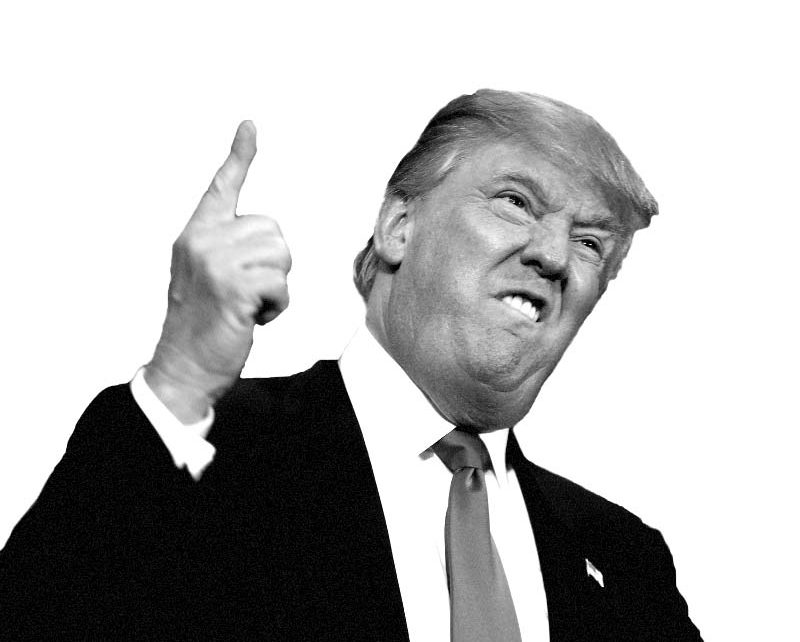

The world is heading for a disastrous breakdown, if current levels of consumption – and the attendant depletion of the earth’s resources – are allowed to continue. The global picture looks increasingly bleak, with far right governments, including the US under Donald Trump, reneging on the commitment to reduce carbon emissions. But rather than conceding defeat, we must fight even harder to play our part in the battle to achieve sustainability with honour – and imagination...

Whale-watching off the coast of Cork has closed down. The cetaceans have gone, thanks to overfishing. Sprats, a major part of their diet, have disappeared, swept away in the deep-sea nets of giant trawlers.

The environmental crisis into which we have stumbled takes many forms. Hardly a day passes without another loss, another warning sign.

It’s forecast that the world will run out of topsoil in fifty years. That is not very long, when you consider that anatomically modern humans are estimated to have emerged about 300,000 years ago.

So too, apparently, will sand. It may be essential to the vast global construction industry, but there’s only so much of it out there.

It’s running out on land, so it’s now being slurped from the sea using suction dredges.

China is far from the only country doing it, but it’s doing a lot of it, lifting more than 100,000 tonnes a day, it was alleged a few years ago.

Meanwhile, it’s predicted that sea levels will rise by 0.3 metres by 2050 and at least 1 metre by 2100, at potentially huge cost in terms of coastal erosion, and flooding in low-lying cities.

But if polar ice melting picks up speed, as now seems to be happening, those predictions are way too low.

Paradoxically, at the same time, the world is running out of water for drinking, and for industrial use.

Yeah, sure, there’s an awful lot of it about, in both rising seas and torrential storms – but it’s in all the wrong places at all the wrong times.

The reality, in short, is that we’re consuming too much of everything.

So much so that some day, maybe soon, and especially if Donald Trump gets his unfettered way, there’ll be nothing left to consume but ourselves. Humans, the last remaining commodity? I wouldn’t bet against it.

How Bad Is It Really?

All of that is before we factor in the colossal damage being caused right now by military activity and wars. Israel’s destruction of Gaza is estimated to have increased emissions by in the region of 450,000 metric tonnes of CO2 equivalent – more than the annual emissions of 33 countries. In other words, it is a massive environmental disaster.

So far, then, the 2020s have seen a major acceleration in the world’s climate crisis, even without the full frontal assault on climate science that is planned – and is already being activated – by the Mar-a-Lago brass and reed band and their fellow travellers.

Which means that it’s not looking good for the global ambition – agreed at the Paris summit – to hold average global temperature to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

Not that Ireland is in any position to lecture the rest of the world on the issue.

It is looking very unlikely that we will meet our own target to deliver a 42% reduction of emissions, by 2030 – taking 2005 as the starting point – under the EU’s Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR).

Hefty climate fines loom for Ireland. Very hefty, in fact. What former Minister for Finance Michael Noonan might have termed millins and billins. And this is money that will, inevitably, in some shape or form, come out of the pockets of Irish people.

So, is the glass half-empty or half-full?

Or are we way beyond that test of attitude? Have we reached the point where we should be digging safety silos, and using the rocks and clay we extract to build Dutch-style dikes and polders to keep out rising seas?

Now, that’s a bleak prospect altogether, given our extraordinary inability to build houses or infrastructure.

But before you despair entirely, consider this: Trump’s chaotic tariff campaign has generated serious turbulence in the financial markets – that is, among the faceless but very powerful people who deal in bonds and stocks and government debt.

They don’t like what they’re seeing and hearing, especially when they look at the scale of US government debt, and how much of it is owned by foreigners, especially in China, Japan and Europe.

It hasn’t stopped Trump, who seems incapable of controlling his impulses – but it shows that global players make their own moves. They’re faceless and ruthless and they don’t do deals. The boundaries have been set. The dollar has fallen 10% against the euro at the time of writing. It may drop further.

Donald Trump may be digging a very big hole.

Are There Any Green Shoots?

Something very similar is likely to happen down the line regarding climate change. If things get really bad, it will not involve any human agency.

It’s the earth itself that’ll call time.

Those who are in denial can dispute the facts all they like but, as Memphis Minnie once sang, “When the levee breaks the water’s gonna overflow.”

Who knows what’s coming? Big volcanoes are spewing and there are rumblings in calderas – those ‘centre-holes’ in volcanic sites – in Yellowstone and Naples. If those things blow, no human action or abstinence can make a blind bit of difference. A blast could mark the end of most of what we know.

So, to repeat: we need to act. The words of Virgil Kane, the narrator of The Band’s ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’ have been playing on my mind: “Now, I don’t mind chopping wood / And I don’t care if the money’s no good / You take what you need / And you leave the rest…”

It’s an expression of sustainability and solidarity. The micro and the macro matter. You control what you can control. You do what you can do. Ideally, we need everyone thinking the same way, doing it together. But it is all about momentum.

And, in that regard, there’s some serious good news.

China, for so long bound by old smoky technologies, now leads the world in electricity generation. In 2024, it produced over 10,000 Terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity, which is greater than the combined output of the US, the EU and India.

China also produces the most wind and solar energy. Its wind energy output is three times the size of the US’s. Better still – for China, but for the world too – its solar output is over four times greater that of the US.

Smaller countries are making even more progress. Brazil, Vietnam and Poland have exceeded an annual growth rate of 120% over the last 10 years.

Solar power is Brazil’s second largest source of electricity.

And China, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, and Singapore have all made carbon neutrality or net zero pledges.

Meanwhile, the EU’s gross available energy – a key measure of the energy produced for use – fell by 4.1% in 2023. That’s the equivalent of saying that about 380 million barrels of oil were no longer needed – marking a record low.

Admittedly, the EU is still heavily reliant on fossil fuels (67%) but renewables now supply 19.5% of all energy in the EU. That’s up 31% since 2013.

Nordic countries, such as Sweden, Finland, and Denmark lead the green transition, with renewables accounting for 40–50% of their energy mix.

There are exceptions, of course. Poland and Czechia still rely on coal, with solid fuels – fossil fuels not including oil or gas – still supplying roughly a third of their demand.

As for Ireland, we’re well down the field in terms of performance. But at least we’re up and running.

Our carbon emissions have been pushed 3.3% below the 1990 baseline for the first time in 35 years.

But there’s no disguising the fact that we’re way off where we need to be. And the problem may be about to get even more serious. According to the National Economic and Social Counsil, “Much of Ireland’s policy action for transition in the power sector is headed into fog.”

In a similar spirit, last April, the Irish Academy of Engineering (IAE) asserted that energy policy in Ireland needs to go beyond wishful thinking and be driven by the realities of engineering, finance and project delivery.

Ouch.

Making The Circular Economy Work

Obviously, in the midst of global shitstorms we can only do what we do. But the truth is that we have to go beyond green faith (of which there’s far too much) and recognise what is going on in the real world – and how that might just be of assistance to us, in our specific battle.

The way that other countries have tackled energy generation and consumption shows the urgency of the task.

Forgive me for saying so, but it’s not about data centres.

Indeed, it’s really irritating to hear people who spend their whole lives on their phones – and use oceans of juice streaming reams of content – complaining about the energy demands of data centres.

The sustainable thing to do is to use the phone less!

The contradictions are endless. In a similar vein, there are those who live in rural areas and are therefore most dependent on electricity supply being delivered at a loss, but who still routinely oppose wind farms.

All the available evidence says that we have a huge advantage in the production of energy from wind. So let’s get on with it!

And there are those who oppose airline travel and yet, under the umbrella of wellness, consume loads of blueberries and avocados and dozens of other foods that are considered healthy but which rack up many thousands of air kilometres on their way here.

So here’s a different way of approaching the issue. Let’s start to accentuate the positive, and find the virtuous circles that make the circular economy work. One example is how data centres and district heating can go together, as in the Tallaght District Heating Scheme.

What you have there is a distributed energy system and it resolves several problems at once, using the waste heat to supply a service that would otherwise demand significant levels of energy.

Systems of that kind see fewer energy losses during transmission because they’re generated so close to the site of ultimate usage. And they can be built very quickly.

Tallaght District Heating Scheme

There’s more fresh ideas where that came from.

We should, for example, also be enthused about the innovative thinking behind a new road-building technique piloted by Monaghan County Council which cuts carbon emissions from roadworks by more than 50%, by using a composite material that incorporates used asphalt.

Likewise the new sewage treatment centre in Arklow, which has garnered a great deal of praise in recent months for its design and unobtrusiveness, and the way it will facilitate the development of a major new housing area.

So, yes, there are reasons to feel positive. We can do these things, and make a difference. But we should be doing a lot more.

Up here on Hog Hill, we’re also excited by a breakthrough in small wind-turbine technology.

There are several examples that are nearing effectiveness and should be on sale shortly. The coolest is the Vind Panel, a modular wind turbine system that can produce up to 5 kW of electricity – and even up to 400 kW for larger installations. That’s enough to offset significant residential power demand.

It’s like a wind version of solar panels.

Basically, it’s a framed series of compact vertical wind turbines that can double as a fence or wall installation. Alternatively, there’s the option of positioning it on a roof – or, in a public context, on a highway, at an airport, or a school. Or it can be combined with solar panels in a hybrid energy system.

The panels are designed to operate quietly. They look good and keep going 24/7, in rain or shine – or, best of all, in low wind conditions. Additionally, they’re made from recycled materials, including reused metals and plastics, supporting the circular economy model.

Bring ‘em on!

We Need To Play As A Team

Green innovation is hugely exciting, whether it’s new housing technology, experimental engines, transport innovations, new crop varieties and animal feeds that reduce carbon emissions. There’s also research into algae and plankton, with the objective of developing new crops and foods; carbon-gobbling spreads for fields; new ways of cleaning the seas of plastic; and the possibility of developing plastics that dissolve in seawater.

Will they all work? No! But those that do have the potential to make a major contribution to enabling us to achieve the changes necessary.

Then, in parallel with the scientific and technical innovations, we see other, more socially-driven changes, like the pivot towards reducing waste by repairing rather than replacing.

The campaign launched by Patagonia – “If it’s broke, fix it!” – is an example.

The company’s view is that “Some things are simple. Repairing your Patagonia gear is one of them. One of the most responsible things we can do for the planet is to keep our gear going longer. That’s why we’re making it as easy as possible to repair.”

Such developments – in district heating, street-scale energy technology and repair and reuse of materials and objects – seem to mark a return to values first expressed in, for example, Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered (1973) by German-born British economist E. F. Schumacher; and similarly of the Slow Food movement launched by Carlo Petrini in Italy in 1986.

Which is why it is so disappointing that Ireland isn’t to the fore in sustainability and Green innovation. We see ourselves as creative and adaptable. As having entrepreneurial skills. As people who care about others as much as ourselves.

Instead, in this context, we seem complacent and risk-averse, comfortable with letting others do the experimenting, innovating and development.

Which begs the question: why aren’t we lead innovators? And why, for example, do the Danes do it better?

The answer has many strands.

For years the get-out explanation for Ireland’s failings has been post-colonial inertia – but after a century of independence that’s worn itself out.

No, the truth is that our political and administrative structures and processes are far too slow-moving, cautious, conservative and generally hidebound.

As a result, our planning, fiscal and education systems don’t encourage innovation, risk-taking and enterprise, and our research capacity is limited.

We do have great talent and excellent entrepreneurs but insofar as these prosper it’s because of their own grit, determination, resilience and luck. Or they relocate to work in the UK, the US or in different parts of Europe.

Well, we really urgently need to change that – to open the windows and let the light in.

In particular, our planning needs to shake off the dead hand of managerialism and box-ticking, and focus on strategic direction, and on liberating systems for delivery.

We’re inextricably entwined in a dynamic, frequently volatile, global environment (or ecosystem), so things can and do change, very, very fast – and we have to be flexible of mind and fleet of foot to adapt our plans and actions accordingly.

If we don’t make the necessary changes – and fast – we’re toast. But to make those changes happen will require bravery on the part of politicians. It will need an effective campaign of encouragement and education. We must succeed in getting people living in Ireland to work together, in a spirit that is informed by an awareness both of the imminent dangers and of the greater good – rather than everyone scrabbling for individual advantage.

Our motto for the emerging future? Think first, then move fast, and fix things.

The good news is that it can be done. But only if we start to really play as a team.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 31 Dec 25

Climate crisis: "The battle must go on. The alternative is unthinkable"

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 07 Oct 25