- Opinion

- 06 Aug 25

Remembering Hiroshima 80 years on: "August 6 should be a day of global silence, a day when we contemplate the terrors of war"

But it was as far from a wonderful day as it is possible to get, when the crew of the Enola Gay dropped atomic bombs – first on Hiroshima, and later on Nagasaki, in Japan. As we approach the 80th anniversary of that cataclysmic event, there is a need for us all to recognise the monumental folly of war.

…We screamed into a steep diving turn to escape the shockwave… Then we turned back to look at Hiroshima. But you couldn’t see it. It was covered in smoke, dust, debris. And coming out of that was the mushroom cloud.”

Thus spoke Theodore “Dutch” Van Kirk, as recorded twenty years ago by Stephen Walker, author of Shockwave: Countdown to Hiroshima.

On August 6th 1945, Van Kirk was the navigator of the US B-29 bomber Enola Gay that dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“It was a beautiful morning,” Van Kirk told Walker. The sun was shining, the city clearly visible for 50 miles.

Until it wasn’t.

Three minutes after they dropped the bomb, Hiroshima was gone.

As the US servicemen flew back to base they could see the mushroom cloud 400 miles away.

The explosion was equal to 13,500 tonnes of high explosive and the destruction was instant and absolute.

People were literally vapourised, only their shadows remaining, imprinted on walls.

In his outstanding book Question 7, Richard Flanagan describes four silk powder bags containing cordite detonated by “a tiny explosion that in turn initiated the largest man-made explosion in human history.”

At which point, he bleakly notes, the bags were just vapour and energy “along with the 60,000 Japanese souls ascending with them to heaven.”

Or perhaps it was 80,000. Or 145,000. There are many estimates, but nobody actually knows how many people died instantly.

The US forces’ final assault on Japan was planned for Kyushu in November.

They had pounded Japan from the air and were picking their way from island to island. There had already been 300,000 deaths and 9 million people were homeless.

There was desperate resistance but also great hunger.

There are harrowing descriptions of mass suicides.

The Imperial army had ordered that everyone fight and then commit suicide rather than surrender.

This, in effect, was a call for the mass suicide of 100 million people.

Forestalling such a cataclysm was one reason given for dropping the bombs – though, of course, another was to save Allied lives and energies for the world that would follow. And besides, there is the question: were the bombs necessary to achieve the ends that followed?

DEATH RAILWAY

Re-reading the course of events, one is struck by the randomness of what unfolded and the role played by fate rather than plans. It is a theme that is central to Flanagan’s book: the utter contingency of his life in particular, but also of life and death ingeneral.

For example, the second bomb wasn’t meant for Nagasaki. It was meant for Kokura.

But the day’s weather was unfavourable. There were technical glitches and the plane was running low on fuel. So they dropped the bomb on Nagasaki instead.

Another 40,000 people were vapourised. Or was it 60,000? Or 80,000?

One minute they were about their business, and then they were dust, vapour, atoms.

Nobody deserves such a fate. In Unforgiven, the gunman William Munnie (played by Clint Eastwood) tells Sheriff Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman) “deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it.” That’s the way war works.

Richard Flanagan’s father was a prisoner of war in Ohama Camp, 80 miles south of Hiroshima when Bombardier Ferebee pulled the lever.

He was in his fourth year of captivity and was sure that he couldn’t survive another winter. But now he was now going to live.

In the book Flanagan wrestles with many things. One of them is his father’s survival and, in turn, his own subsequent birth. But for the bomb, he wouldn’t be.

But that’s life. And death.

We’re all going to die, even Elon Musk. Life teems with threats. We remember, for example, US General William Westmoreland, commander of the US forces in Vietnam from 1964-1968.

On his watch, a top secret contingency plan named Fracture Jaw was prepared, making nuclear weapons available for use at short notice against North Vietnamese troops.

Fortunately, it was abandoned in 1968, having been outed by, among others, Senator Eugene McCarthy.

Imagine the consequences had such a plan come to pass.

Even without a nuclear bomb, that war took the lives of millions of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians, Cambodians, Laotians and US service members. There was a famine and, in truth, nobody knows how many died. This is the evil perpetrated during wars.

Nameless and forgotten millions died in Russia in World War I, the civil war, collectivisation and World War II. The same can be said of China and, in the 1980s, Iran and Iraq.

Around 250,000 Russians and 100,000 Ukrainians have died since the Russian President, Vladimir Putin, invaded back in 2022. And tens of thousands have died in Gaza since October 2023. Again, we don’t know what the real number is.

Look in the eyes of those you love and think of the pain and horror if they were wiped from the face of the earth from on high.

Remember the agony that follows a car crash death in Ireland. Multiply that a hundred thousand times and more.

Each death is unique to the dead and his or her family and friends, and all are equal in the grave.

Let nobody try to reassure us with weasel words like “collateral damage.”

Let nobody try to assuage their guilt by saying “bad things happen in wars.”

Let nobody spout bollox about smart weapons and pinpoint accuracy.

These are lies. At the personal level, the bombs of the powerful are wholly indiscriminate and massively lethal.

Those vast numbers aggregate into an unspeakable terror and trauma.

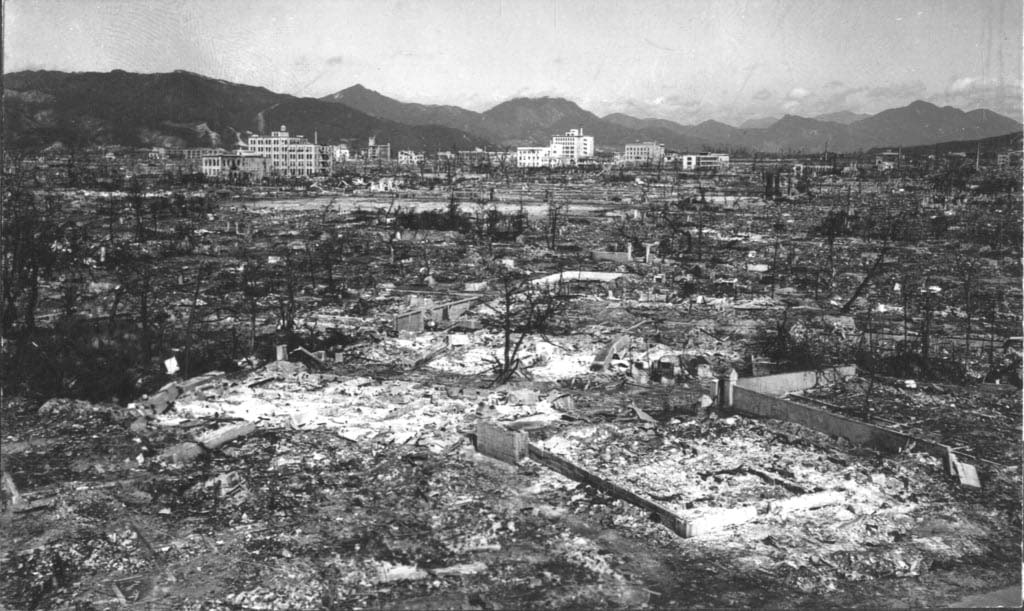

Hiroshima after the atomic bomb.

Hiroshima after the atomic bomb.A BIPOLAR STAND-OFF

Of course, we can’t deceive ourselves that all lives are of equal value. They should be, but that isn’t the way power works.

Bomb and bullet aren’t the only causes of death, or of war crimes, in war zones. Hunger and disease are there too.

As Flanagan reminds us, more people, many of them captured Allied prisoners of war, died in slave labour on the Death Railway – aka the Burma Railway – than died at either Hiroshima or Nagasaki.

But, he wonders, “Do possibly more corpses tomorrow justify fewer corpses today?”

It’s never right to kill a city of people. But what, he reflects, if it saves the lives of fifty times as many? As Flanagan says, we can only pretend that we have answers to such a question.

Those bombs, one theory goes, marked the end of half a century of tumult, war, violence, authoritarianism. Would that have happened anyway? You can never know, because undoing what has been done is only for movies or fiction.

But this much we can say.

For all its challenges, the half century after the end of World War II was a time of relative stability and growing prosperity, at least in what we call the West; and even – in parts of the world – of social progress. In the UK, for example, they introduced the Welfare State.

To one degree or another, that peace was based on the Cold War, a bipolar standoff between the USA and USSR, both nuclear powers – but both also, on the face of it at least, committed to not taking the world over the edge.

It ended with the fall of the USSR and the apparent “victory” of western economic neo-liberalism.

Since then, chaos has steadily built, exacerbated by vast, largely ungoverned developments in technology, an ever-increasing gap between rich and poor, the collapse of old ideologies and, of course, increasingly out-of-control climate change.

So here we are.

TERRORS OF WAR

Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Russian roulette. Those two bombs – like modern cluster bombs, missiles, drones and bunker busters – show where power and technology can bring us if left unchecked and if those who deploy them lose a sense of common humanity.

All that said, we need to be both honest and pragmatic about what can follow the repetition of these cataclysms.

As Richard Flanagan asks, “What if vengeance and atonement both are simply the lie that time can be reversed and thereby some equality, some equilibrium restored, some justice had? Is it simply truer to say that Hiroshima happened, Hiroshima is still happening, and Hiroshima will always happen?”

If not there, then elsewhere.

August 6 should be a global day of silence and reflection, a day when we contemplate the terrors of war and where, if unfettered, it leads. Look at Ukraine, at Gaza, at Sudan...

What’s so funny about peace, love and understanding? Nothing. Nothing at all…

• The Hog

RELATED

RELATED

- Opinion

- 30 Jan 26

Neil Young announces that he will stop supporting Verizon and Apple

- Opinion

- 30 Jan 26

Culture Ireland set to receive over €1.6 million in funding

- Opinion

- 29 Jan 26

Meet the DkIT Musical Theatre students behind Kismet Theatre Company

- Opinion

- 29 Jan 26