- Music

- 13 Sep 24

Album Review: Bob Dylan and The Band, The 1974 Live Recordings

Anne Margaret Daniel reviews the upcoming 431-track collection of Bob Dylan's 1974 arena performances with The Band – out September 20 (Sony/Legacy)

Being on tour is like being in limbo. It’s going from nowhere to nowhere.

— Bob Dylan, on tour with The Band in Philadelphia, January 1974

This is the craziest, the most undisciplined and the strongest rock and roll ever recorded.

— Robert Christgau, review, Before the Flood (1974)

Before the Flood was the first Bob Dylan album I bought with my own money, seventy-five cents, when I was a kid at a yard sale in Richmond, Virginia. Though I knew and liked Dylan from a couple of my parents’ Folkways albums, I knew nothing of the music within. But I liked the cover: the bowl of a concert in nighttime shades of red and black, lit up by hundreds of Zippos and matches held aloft, or so I thought.

I got it home and listened to it, and never looked back from an immediate, passionate, now lifelong love of The Band, and particularly for their singing drummer. Fifty years are past since this album was released; and now we have, in celebration of its anniversary and the anniversary of the remarkable tour when Before the Flood was made, the gift of Bob Dylan and The Band: The 1974 Live Recordings (Sony/Legacy, September 20, 2024).

Take crazy, undisciplined, and the strongest rock and roll ever recorded, and multiply that by four hundred and thirty-one: 27 cds of music, if you order the whole shebang of The 1974 Live Recordings in that old giant-sequin medium (alas, this one is not being released on vinyl). If the thirteen tracks on Before the Flood blew Christgau’s doors off, just try to imagine what The 1974 Live Recordings will do to you.

I’ve been listening for a month to Dylan’s performances, solo and backed by The Band, from Chicago, Philadelphia, Toronto, Fort Worth, New York, Atlanta, Los Angeles…. 41 shows, frequently two a day, afternoon and evening, from January 3 at Chicago Stadium through Valentine’s Day at the Forum in LA, playing to an average of 18,500 people a night in cavernous venues. After a break from live performance since he’d appeared – each time with The Band – at a Woody Guthrie Memorial Concert in 1968 and two festivals in 1969, Dylan turned every bit of his considerable energies as a performer into making what Elizabeth Nelson calls, in her excellent liner notes to the new box set, “a rough and ready reentry into the troubadour game.”

Not every show on the tour is included here. The box set is careful to say that “all professionally recorded shows” are featured here, and that leaves out quite a few. None of The Band’s interspersing solo sets are included, either. This is such a pity. Certainly it’s because of licensing and copyright issues; The Band’s albums were primarily released on Capitol, and Dylan’s been a Columbia recording artist for almost his entire career. However, the omission leaves raw holes in every evening and feels discontinuous, historically inaccurate.

On the bootlegs you know and love, particularly the vast Build A Ladder To the Stars, The Band’s performances interweave with Dylan’s sets into a musical tapestry that leaves you knocked out cold. Those explosive 'Stage Fright's with which The Band generally began their sets, Rick Danko’s aching sky-arching vocals on 'When You Awake', and Levon Helm’s concluding benedictions of 'The Weight' would have added much to this compendium.

However, it would also have added ten or eleven songs per night to a box set already oceanic in its sweep. This was a similar problem for the Rolling Thunder Revue box set, which contains only Dylan’s sets. At least on The 1974 Live Recordings we have The Band’s instrumentals and harmonies as they join Dylan. Historically, they’re among the few men on stage with him as his band who are not just occasionally permitted, but ever welcome, to sing when Dylan is singing. And he’s never played with such raging glory, with such an untouchable band of brothers, since. Play it fucking loud: that is the mantra of the 1974 tour.

© Barry Feinstein Photography

The men had first begun performing together almost a decade earlier, when Helm, Danko, Robbie Robertson, Garth Hudson, and Richard Manuel – then called, if anything, The Hawks, from their days as Ronnie Hawkins’s backing band – joined Dylan for a slew of dates in the United States and Canada in 1965, and then on his 1966 world tour. He’d famously, or infamously, gone electric at the Newport Folk Festival in the summer of 1965, to the shock and general horror of the folk world for whom he'd become a leading public face.

Some folk fans dug 'Maggie’s Farm' and 'Like A Rolling Stone'. Many did not. In a clip from the tens of thousands of feet of film shot by D.A. Pennebaker and Howard Alk on the 1966 tour, Dylan, shrinking into the back seat of a limo next to Robertson, tugs his hands back from fans reaching in the cracked windows and then repeatedly asks, almost orders, “Don’t BOO me anymore. Don’t boo me, God, they’re booing, I can’t stand it.” The booing continued, though, to the point where Helm quit the band for awhile and retreated home to Arkansas, and thence to the Gulf of Mexico to work on an oil rig. The others, joined by shifting drummers including Bobby Gregg, Sandy Konikoff, and Mickey Jones, persevered through that last landmark night at the Royal Albert Hall on May 27, 1966.

Then they all came to rest, or at least settled, in and around Woodstock, New York. The man who had brought them together, music manager Albert Grossman, lived there, in Bearsville. His wife Sally’s best friend from her New York City days, Sara Lownds, was now Dylan’s wife. Their first son, Jesse Byron Dylan, had been born in January 1966, fast followed by three more children. After Dylan’s motorcycle accident that summer, he receded. Off the road, off the crazed speed in every sense of the word, off the grid, and on the porch up in the Catskills, making music with his friends.

© Barry Feinstein Photography

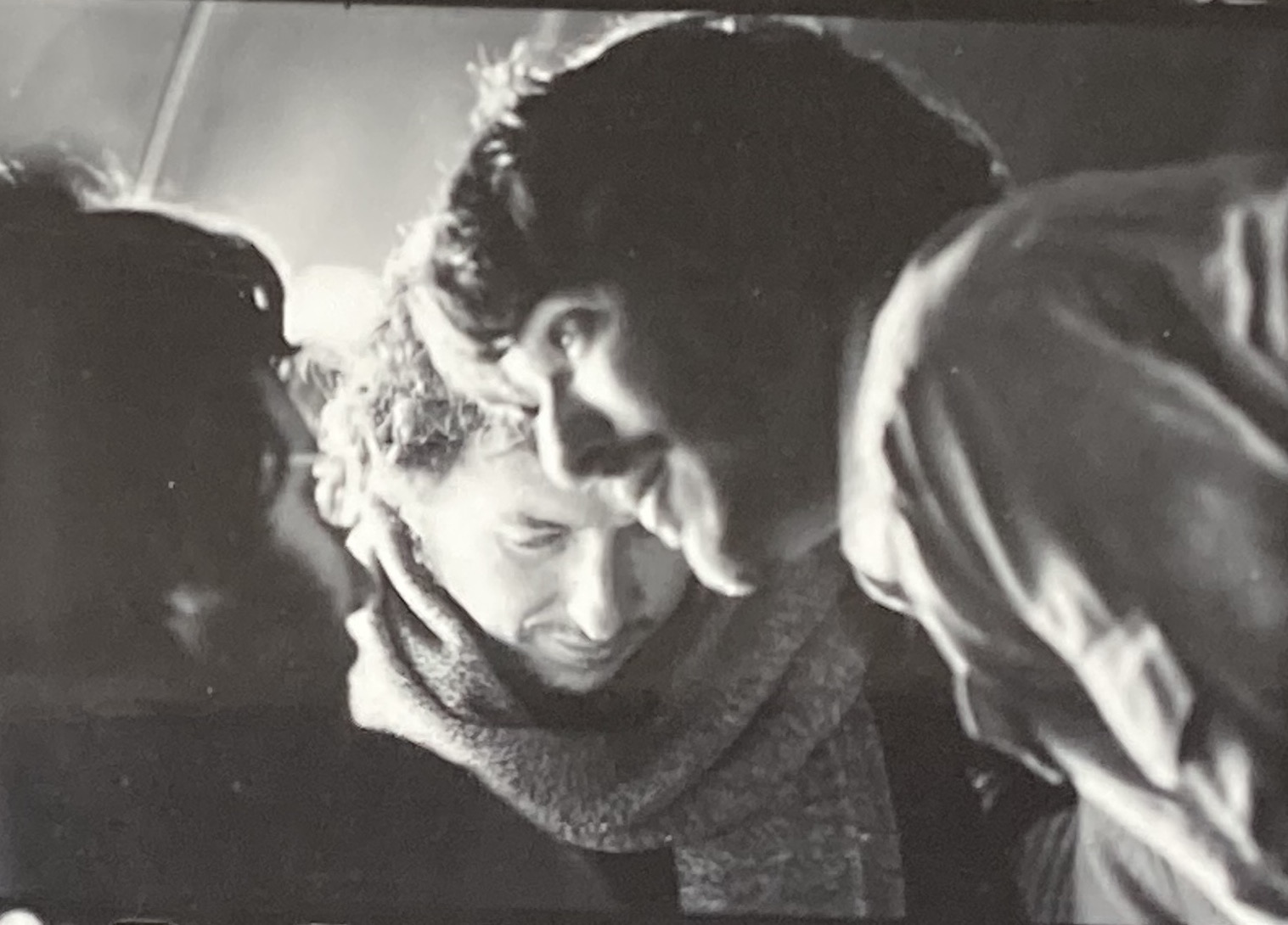

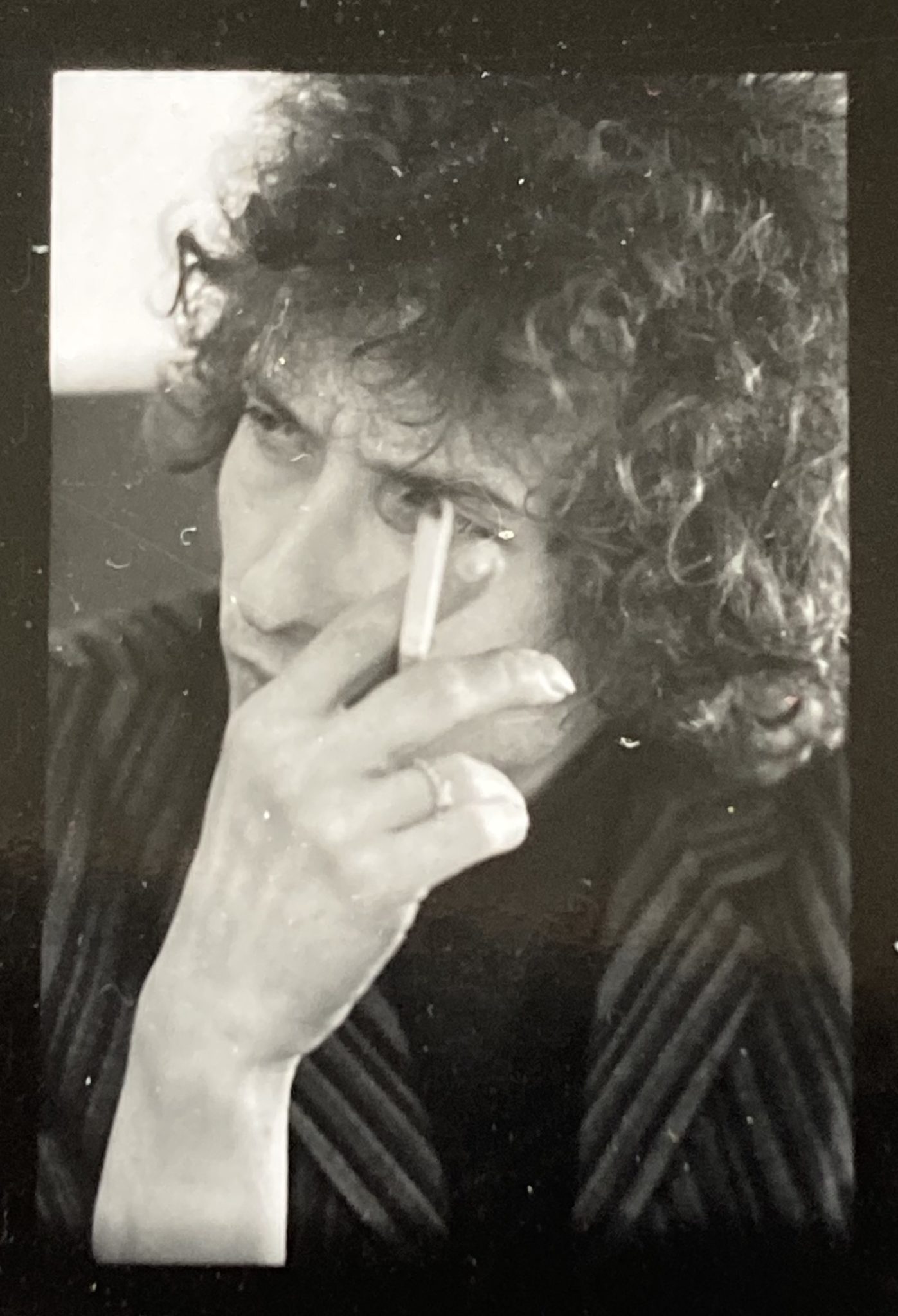

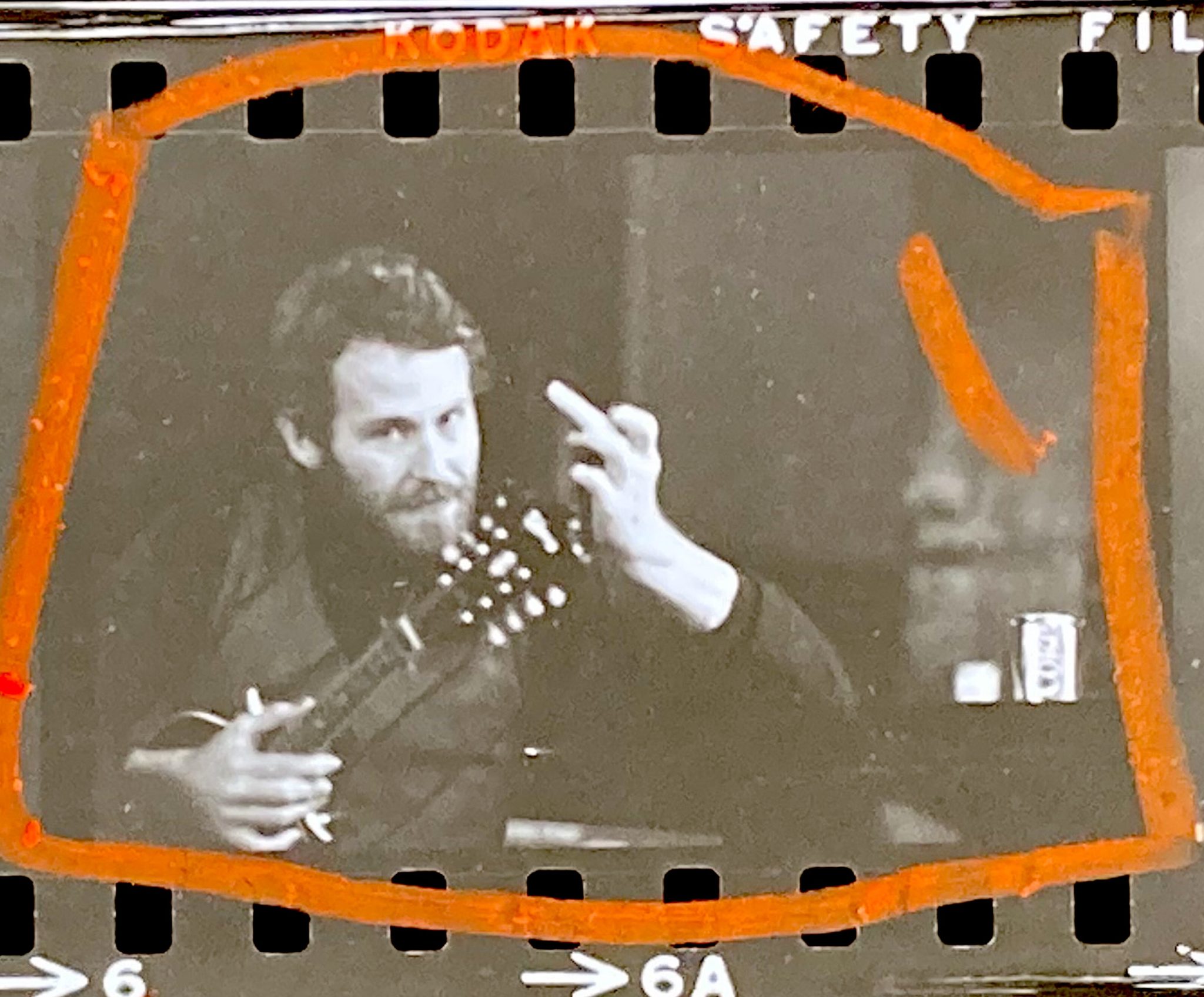

The booklet for The 1974 Live Recordings is illustrated with some of Barry Feinstein’s best-known, and many obscurer or previously unpublished, photographs from the tour. Feinstein, like the men in The Band, had been introduced to Dylan through Grossman. The Philadelphia-born Feinstein got his start photographing the racetracks and beauty pageants of Atlantic City, but made his name as both a photographer and filmmaker in Hollywood in the late 1950s, working for Harry Cohn at Columbia.

A move back to New York, and marriage to Grossman’s client Mary Travers (of Peter, Paul and Mary) in 1963, brought Feinstein firmly into Dylan’s world. When Grossman needed his Rolls-Royce driven back east from Denver in August 1963, he asked Feinstein to drive it, and Dylan rode shotgun. Barry and Bob bonded over crashing a camp meeting and listening to the preaching and music, over racing a freight train in the Nebraska night. The black and white cover portrait for The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964), in which the 22-year-old Dylan looks like an ancient, determined survivor of all America’s past, is by Feinstein. He would continue to photograph, collaborate with, and maintain a friendship with Dylan through his career.

When Dylan and The Band hit the road together in 1974, Feinstein was the photographer hired to take not only photos onstage but moments backstage as well, granted access as a colleague and a friend: Manuel peeing, and grinning, while Robertson checks his look in the mirror; Dylan doing stretching exercises and lying on the floor of his room, his guitar close at hand; Dylan and Helm playing ping-pong.

Remember that album cover for Before the Flood that I, and probably you, loved as a kid? Wearing both his photographer’s hat and that of graphic designer, Feinstein literally handmade it. His album covers were already rock epics: Janis Joplin in her pink feather boa and thousand-watt smile for Pearl, photographed the day before she died; The Byrds in a fisheye lens; Ike and Tina Turner in whiteface, winking as they eat watermelon on the stingingly parodic cover Feinstein designed for Outta Season. For Before the Flood, Feinstein took his photograph of a concert crowd holding lighters and matches –remember, everyone smoked in 1974 – and lit spills of paper aloft.

Still, there wasn’t enough of the right kind of lighting for the image he wanted. On a big clear plastic sheet, Feinstein took white and yellow grease pencils and added the detail to perfect the scene. Think of the world’s coolest overhead projector. That’s how the cover of Before the Flood was designed. To see Feinstein’s art showcased here is pure pleasure.

© Barry Feinstein Photography

The tour and the recorded performances

Occasionally, he runs one over like a truck.

—Robert Christgau, on Dylan’s 1974 versions of his earlier songs

A tour by Dylan and The Band in huge sports arenas was dreamed up by David Geffen and Bill Graham. Graham, born Wulf Wolodia Grajonca in Berlin in 1931, had made a name for himself as proprietor of the Fillmore and presenter of immense music festivals. Geffen was a talent agent and music manager who had founded Asylum Records at the age of 28, and persuaded Dylan and The Band, though briefly, to join the label. For Planet Waves we should always be grateful to Geffen.

Together, Graham and Geffen arranged a chartered Boeing 707 for the musicians and their large traveling crew of wives, girlfriends, children, friends, and whoever else they invited along on various legs. Though Dylan vetoed any filming, he invited his old friend Feinstein (who brought his then-wife, actress Carol Wayne) along to take photographs. The plane had, according to press releases, “every imaginable amenity” including food “from organic and vegetarian to the classic haute cuisine.” Gig tickets cost around $8. Most shows sold out swiftly, and fake tickets abounded. The tour grossed over $5 million, and Geffen proudly said of Dylan to The New York Times, “His appeal is finally as great as his significance.”

People were crazy and times were strange as 1974 began. Reviews of that first night in Chicago, over the weekend of January 4-6, ran next to Jules Feiffer’s syndicated cartoon of an old woman freezing and without food, wondering “Are we impeaching Nixon…or is he impeaching us?” The sitting president, Richard M. Nixon, had been impeached on October 30, 1973, and the Judiciary Committee was gathering evidence about, among other things, a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate Building in Washington, DC.

Listen to the many performances of 'It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)'. The biggest crowd roar on many nights comes when Dylan sings “Even the President of the United States sometimes has to stand naked.” Said one Chicago concertgoer, “That was written in 1965, but it sounds like it was written yesterday. It’s so right on.” It was freezing on stage: the piano tuner could not get the strings to hold a tune until portable heaters were set up under the stage.

The set lists varied a bit, but as you listen to The 1974 Live Recordings, you’ll hear most of the same songs over and over again. Audiences are now used to this from Dylan; but he continues to surprise by dropping in the unexpected if he feels like it. If you’re sorry not to have heard, say, 'Like A Rolling Stone' live since 2019, be heartened by the 22 complete live versions available here. Less well-known songs are compelling, too. That opener of 'Hero Blues’ in Chicago, which didn’t stick around for the whole tour, puzzled and dazzled the audience: twelve bars of decade-old Witmark Demo blues, about a gal who, among other faults, has read too many books. In it the singer also steadfastly refuses to be anyone’s hero, which is quite an opening statement for Dylan in front of tens of thousands of adorers.

A song one reviewer identified as “a new Dylan ballad, probably called ‘Except You,’ which is one of the prettiest things he’s written” garnered notice, as did 'Forever Young' (“his new and somewhat sugary ode to his over-30 fans,” said a clueless writer). After “a roaring ovation, with thousands of matches and cigarette lighters held aloft in the traditional call for an encore” Dylan and The Band generally returned for 'The Weight' and 'Most Likely You Go Your Way (and I’ll Go Mine)'. 'The Weight' was already The Band’s most popular anthem –and one to which Dylan, interestingly, retains the copyright. In his own encore, Dylan was literally saying hail and fare thee well to his audiences by sending them out into the night with one of his best – and he has many –don’t-let-the-door-hit-your-arse-on-the-way-out songs, sung to an about-to-be former lover.

The shows were celebrity events. John L. Wasserman, writing of the San Francisco concerts, noted that Jack Casady, Bob Weir, the Rev. Cecil Williams, Joel Grey, Jerry Rubin, and “a number of the Doobie Brothers” were in the audiences. Wasserman also complained, eloquently, about the “lamentable inattention to the Band. This Canadian group is probably the longest-lived major rock band extant, dating from 1959 (as Levon and the Hawks) and probably, with the Grateful Dead, the ultimate country-rock group. Their playing on the tour has been absolutely essential to Dylan and, indeed, preferable to Dylan’s contribution for some.”

Wasserman went on with a spot-on description of what The Band always did best: “They played together as only a band of such familiarity can play: perfect harmonies, sixth-sense anticipation, a tightness of such subtlety that each number feels as loose as a jam. Each man – guitarist Robbie Robertson, bassist Rick Danko, organist Garth Hudson, pianist-occasional drummer Richard Manuel and drummer-lead singer Levon Helm – is a master instrumentalist but there is little showing off. Only Robertson’s fluid, crackling lead guitar gets any solo space of note. The key is ensemble. And they’ve got a lock on it.”

Dylan, as part of the ensemble, was utterly at home. With these men behind him, as in 1966, Dylan had both the chutzpah and the capable musicians – particularly Hudson, the mystical scholar and gifted revitalizer of ancient musics – to rearrange, improve, revise, and re-envision his songs people knew by heart, giving them new light and fire. That seems to be exactly what a now 83-year-old Dylan still seeks to do in live performance today.

The Band are a living, breathing machine: Helm the heartbeat, Robertson the singing wires of the nervous system, Manuel the rippling blood flow, Hudson the mind, and Danko the spirit. Dylan floats among them in their combined sets like a Doctor Frankenstein, creating his own version of every song anew, night to night. It’s not macabre in the least, though, just celebratory. I’ve never heard happier audience roars on any collection.

There’s no way, really, to talk about the hundreds of performances and what stands out in every track. Some songs you love more every single time. On 'Like A Rolling Stone', the cascade of keyboards before the vocals even begin always made me see Manuel and Hudson in my mind’s eye; and as the men’s voices join Dylan’s on the choruses, the song is fresh and new and exciting, over and over again. Helm’s spectacular, patterned drumming on just this one song makes me wish he and Dylan had played together many, many more times than they did after 1974.

© Barry Feinstein Photography

Outstanding is Dylan’s nasal, trilling delivery of 'Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues', with The Band turning into son jarocho rockers and Dylan singing as if he’s on a stage down in Juarez, standing there trapped, unable to make his getaway. Helm’s cymbals in particular shake, rattle and roll this song into perfection every time. 'Happy Saint Valentine’s Day', Dylan deadpans, even as the searing lyrics linger in your ears, at the end of the very best rendition of this song in Los Angeles.

On 'Highway 61 Revisited', Helm’s finest rock drumming, Robertson’s blazing guitar, and the flourish and sass from Garth Hudson and Richard Manuel – they could all follow Dylan’s vocals in their sleep. Dylan attacks the song, shouts it. 'Just Like A Woman' has never sounded better and never will. The way Dylan draws out that “gir….rrr..uhl” and gives most of the words extra syllables occupies your mind and imagination in a way I can’t explain, and can only enjoy.

He absolutely rubs your nose in all those scorching 'Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine)'s. Dylan’s voice is on fire, full of urgency, proselytizing, challenging, in your face, yelling, begging, demanding, not giving a single damn, risking and revitalizing everything. These are the hallmarks of his performances throughout The 1974 Live Recordings: come on, boys, let’s rock and roll. Once more, with feeling, play it fucking loud.

All images courtesy of and © Barry Feinstein Photography and may not be reproduced without direct permission.

© Barry Feinstein Photography

RELATED

- Music

- 17 Jan 26

On this day in 1974: Joni Mitchell released Court and Spark

- Music

- 25 Nov 24

50 years ago today: Nick Drake died, aged 26

- Music

- 21 Jul 24

On this day 50 years ago: Rory Gallagher released Irish Tour '74

RELATED

- Music

- 17 Jan 24

On this day 50 years ago: Joni Mitchell released Court and Spark

- Music

- 25 Nov 22

On this day in 1974: Nick Drake died, aged 26

- Music

- 08 Nov 21